Wendy Cowey on Literate Orientation

Literate Orientation on Books with Illustrations.

Make sure all students can see the text of the book. It can be enlarged or projected onto a screen. Starting with the cover, begin a discussion about the illustrations that bring- the story to life and shows students what fun, interest and support can be drawn from looking at them.

A challenge for teachers starting to use this strategy is to tell students about how to look at the illustrations and what is important in them, rather than asking questions. Questions come when there is some shared knowledge established to provide answers.

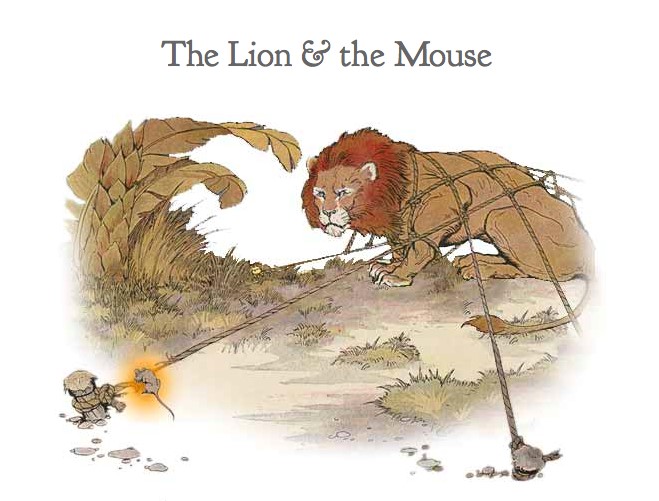

For example, in [a] lesson ... on ‘The Lion and the Mouse’ a teacher might tell the students, ‘This story is about a tiny little mouse who helps a big strong lion.’ In lesson two then, the teacher can then ask, ‘Who can remember who this story was about? The lion was big and strong, wasn’t it? What do we know about the size of the mouse?’

In preparing for ... Literate Orientation read the story carefully as you examine the illustrations and consider the following points as possible topics for discussion:

- The context for the story: this includes the setting, the characters and an overview of what’s happening.

- The theme of the story, the type of story (eg. folk tale, fairy story, fable), the purpose of this type of story in literate culture (eg. why do people read and enjoy this type of story).

- Identify how the illustrations in the story expand, qualify or extend the text content. Authors of books for younger students can choose simpler wording that is easier for less experienced readers to decode by using illustrations to do some of the descriptive work.

- Look for how the illustrations influence readers’ feelings towards characters (eg. do we identify positively with a happy smiling character, do we feel that a mouse with ragged clothes deserves good luck, are the settings for the characters dark and sombre and thus threatening or are they bright and positive).

- Consider the motivations the characters might have had for the way they behave (eg. what feelings are portrayed in their facial express ions and postures, or positions; what power relationships are implied by the positions of characters in illustrations).

- Identify the plot structure (orientation, complication, resolution, coda) and look for how this structure is illustrated.

- Identify wording in the story that could be problematic for a class because of its complexity, the concepts it implies, its unfamiliarity, its difference from spoken language. Then look for how the illustrations can help you bring this language into the Low Order Literate Orientation discussion (eg. ‘the mouse wanted to have fun, it wanted to play so it ran playfully over the lion’s back’).

- Discuss what it is in the illustrations readers have to attend to if they are to make inferences about the characters’ behaviour or motives.

- Work out how you can manage the discussion around the illustrations to model the inferences and interpretations a literate person takes from such illustrations while still keeping the students interested and engaged.

- Consider how to continue the discussion about the text over time to allow handover of the literate discussion to the students. From all the possible approaches to the discussion you have at your disposal, narrow the discussion to a focus that will be carried into the rest of the lesson. For example, in the Lion and the Mouse, a first lesson might give an overview of the whole story, returning to a focus on the setting and the circumstances the mouse found herself in when she ran over the lion’s back, intending to play, not annoy the lion. Subsequent lessons would then pick up on the lion’s decision to let the mouse go, another on the lion’s amusement at the thought that the mouse might be able to help him and so on.

Wendy Cowey, Accelerated Literacy Teaching Strategies || Link