Conceptualising by Theorising

321 RIQ

This strategy assists students to process new information

Before engaging with a text or experience students complete a 321 RIQ.

3 Recalls Students recall 3 facts from a recently viewed text or experience. 2 Insights Students identify an insight into the text or experience considering relevance, implications, connections to others, society or school and correlations. 1 Question Students formulate a question about text or experience.

Students then present their 321 RIQ to a partner with that partner asking clarifying questions in order to gain a good understanding of the others points. It is also possible at this point to ask students to share some insights with the whole class.

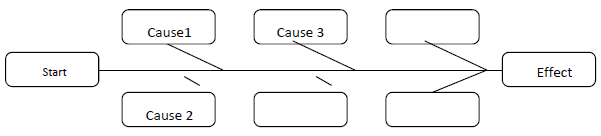

Cause and Effect Pattern Organiser

Create a cause and effect diagram, in which a number of causes contribute to creating an effect.

Character Analysis Chart

|

Facts |

Quotes |

|

Actions |

Inferences about the character’s thoughts and feelings |

Concept Attainment

Concept Attainment is an inductive process that helps bring meaning to concepts or helps construct concepts through the searching for common characteristics. In Concept Attainment students compare like examples and contrast them with unlike examples.

Firstly present the focus statement and the data set. The data set consists of YES examples and NO examples. In maths this might be examples of numbers that are factors of 20 and numbers which are not factors of 20, geometrical shapes and concepts such as area and perimeter. In English it might be a data set of complex sentences, metaphors or spelling patterns. In art it might be about developing understanding of line or texture so the data set will include images. Students then generate, share and test their hypotheses. When students have determined the important attributes of the concept, they then apply it to other examples, extending their thinking. They also reflect on their thoughts about how their thinking progressed during the analysis of the data

Conflict Resolution

Conflict resolution is a way of dealing with disagreements.

- Before You Start: Find out about the person and the background to the problem.

- Negotiating Step 1: Focus on the other person’s view of the problem.

- Negotiating Step 2: Focus on your problem from their point of view,

-

Negotiating Step 3: Step back from the problem.

- Explore the facts.

- Explore alternative, hypothetical ‘third angle’ perspectives.

- Negotiating Step 4: Outline your perspective.

- Negotiating Step 5: Explore consequences of alternative resolutions to the conflict.

-

Negotiating Step 6: Resolution:

- The win/win, feel good stuff (least likely in difficult negotiations).

- Find common ground in a third angle.

- Work out how to achieve something while still disagreeing.

- Agree to disagree; evaluate what was learnt positively from the negotiation experience.

Consequences/Effects Wheels

In the centre circle, write an event, for example ‘Widespread use of solar energy’ Think of and write a direct consequence of this event in an oval and connect it to the centre with a single line. This is a first order consequence. Think of some other first order consequences and draw/write them in. Think of and record second order consequences. These are things that resulted from the first order consequence. Join it to first order consequences by a double line. This tool can be used in analysing critically to examine environmental and societal impacts.

Cubing

Examine a problem in six different ways:

Describe it (features, traits, steps, composed of).

Compare it (similar to, different from).

Associate it (made you think of).

Analyse it (advantages and disadvantages).

Apply it (how can it be applied to other situations).

Argue for or against it (support your position).

Deductive Reasoning

Consider the consequences of theories. What are some of the things that that the theory might predict? What can we expect?

|

Concepts in a theory |

-> Reasoning -> |

Logical consequences of the theory. |

If the theory does not work sometimes, we might need to go back to the facts again, and see whether we can figure out what’s happening using inductive reasoning. Did we create the correct concepts from our facts?

Fishbone

A particular type of concept map – structured like a fish skeleton which is often used to demonstrate how different causes can lead to an effect.

Five Whys

The 5 Whys is a simple problem-solving technique that helps you probe for information and get to the root of a problem quickly. Based on a Japanese philosophy, the 5 Whys strategy is about thinking long-term and looking both ahead and behind, not just in the present. This can be done in twos or threes with the third person being a silent observer. One person takes the role of questioner and the other answers the questions. The questions and answers can be recorded for further discussion and or a final reflection. Very often, the answer to the first “why” will prompt another “why” and the answer to the second “why” will prompt the third “why” and so on. It can show the role of questions beginning with “why” and deepen thinking.

Flow Diagrams

Flow Chart diagrams are useful in examining linear cause-and-effect processes and other processes that unfold sequentially. The student must be able to identify the first step in the process, all of the resulting stages in the procedure as they unfold, and the outcome (the final stage). In this process, the student realises how one step leads to the next in the process, and eventually, to the outcome. They can be used for preliminary planning or, with appropriate annotations, they can represent a timeline or final action plan.

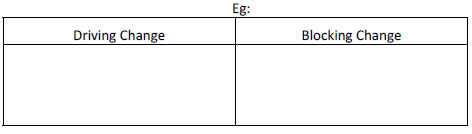

Force Field Analysis

A Force Field Analysis is a visual listing of possible forces driving or preventing change. It is useful for determining what is driving, preventing or slowing change. It teaches students to think together, enhances creative thinking and helps to find a starting point from which to take action.

Lateral Thinking

Think in new and imaginative ways about issues or problems.

- List and describe the usual ways to think about or deal with this issue or problem.

- Search for different or unusual ways to think about or deal with this issue or problem – think of ideas that might seem crazy at first, talk to others, search the Internet …

- Deconstruct: take something apart, work out the connections and patterns.

- Reconstruct: put it back together again in new ways, combinations and patterns. Halve/double, slice/dice, stretch/shrink, substitute, dissect/combine, adapt, magnify/reduce, reverse/turn upside down/inside out, separate/blend, unpack/repackage.

- Look out for the eureka moments, when something suddenly makes sense or comes together in an exciting way.

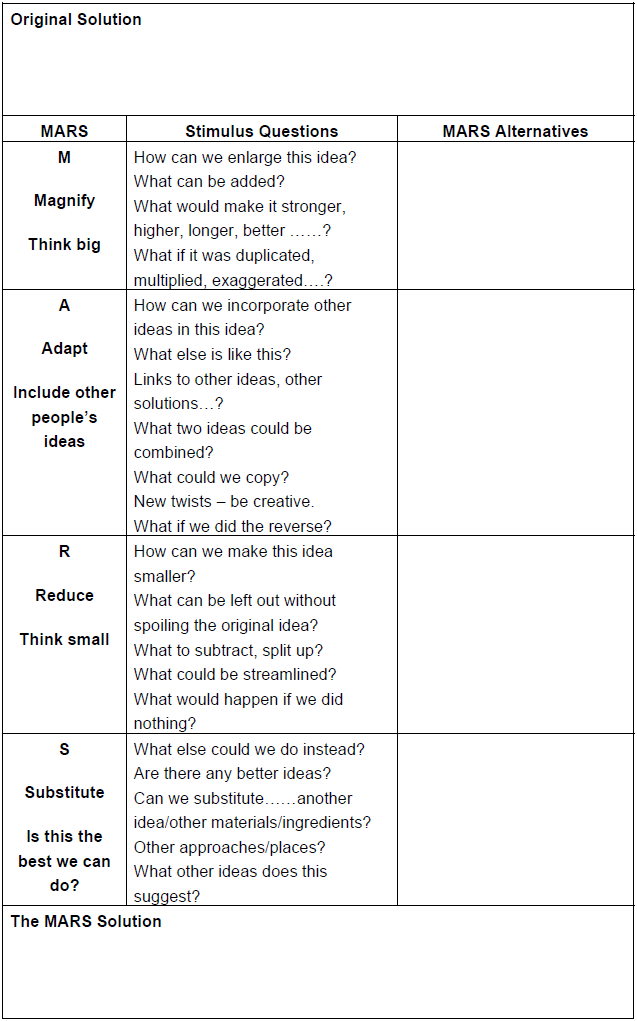

MARS Problem Solving

Mind Map

Take a concept, idea or theme and name it in a circle in the middle of the page. What follows is a visual version of a stream of consciousness. Draw lines branching out indicating linked ideas, with words on the lines. Use different colors to indicate main lines of thought.

Modeling

Create a model (an actual model, or a diagram, or a description) which captures the essence of a theory by showing how its key concepts are connected.

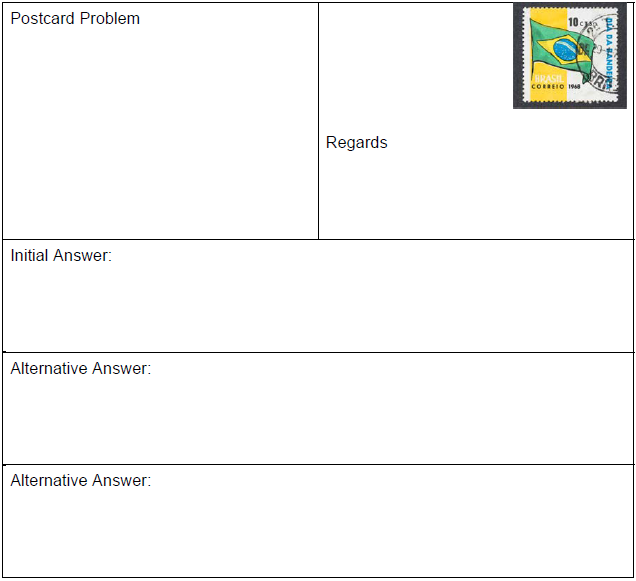

Postcard Problems

In pairs or small groups students develop key questions on the concepts being studied and record them on the postcard in the Postcard Problem section. Questions should be open-ended and complex. They record an expected answer on another piece of paper or in their books. Postcards are then ‘mailed’ to another pair or group who discuss the problem posed and then record an answer to the problem with an explanation or justification. The postcards are collected again and delivered to another pair or group for an alternative response. This can be repeated a number of times and then the postcards are returned to the senders. The senders consider the responses, compare them to their original response and then share/record their reflections.

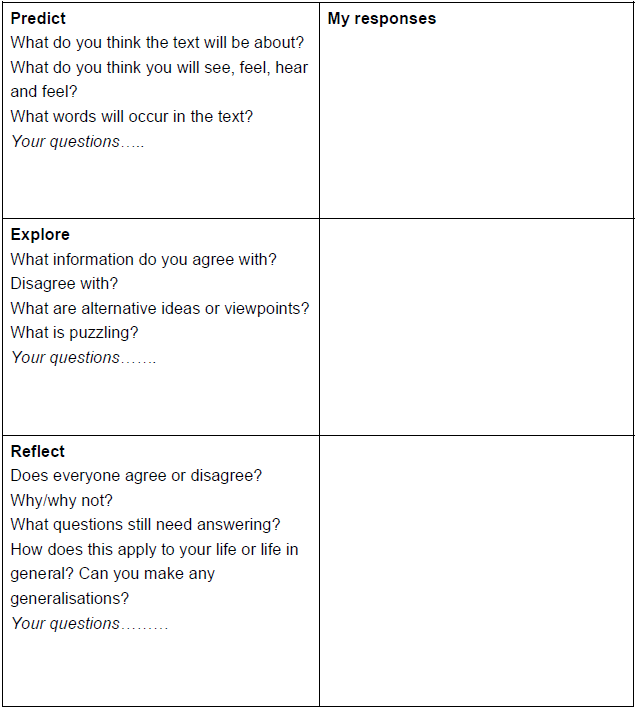

Predict, Explore, Reflect

Select at least one question from each section or create your own. After viewing or reading the text, write your responses.

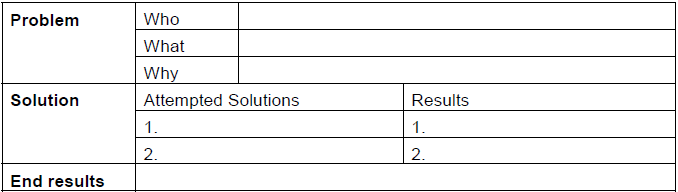

Problem-Solution

Role Play and Freeze Frames

This tool enables students to move their conceptual understandings into other dimensions such as ethical and moral. The teacher develops a series of roles which are written on cards. These roles will be related to the topic or big understanding. The teacher can follow the following format in role play:

- situation and task of characters

- name of character

- background of character.

The roles could also be based on images created by students. Students then create the roles within the role play or prepare a written profile based on the chosen format. After the role play it is important for students to debrief and discuss their presentation of the role and how they felt in that particular situation. It is also important to ensure that all players know that the role play finishes in the classroom.

Students can also be asked to create a freeze frame, a frozen moment of their role play, sometimes called a tableau. Other students could comment on what is represented in the freeze frame – a theme, value, issue, characterisation etc. Students can be given the same scene to represent, different scenes or variations on a theme. A discussion and /or reflection are important to consolidate learning.

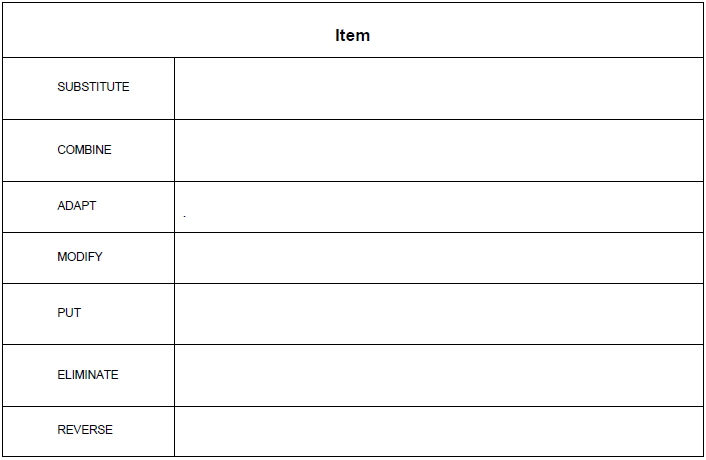

SCAMPER

First brainstorm (and list) and then use S.C.A.M.P.E.R to try to improve it.

Scenario Cafe

Imagine the future, imagine alternatives using the scenario cafe methodology.

Key question about the future: ….

- What if? Brainstorm alternatives.

-

Scanning the horizon and examining the drivers of change

- Environment

- Politics

- Economics

- Culture

- Technology

- Flesh out the scenarios:

|

Best Case Scenario |

Worst Case Scenario |

|

|

Alternative 1 |

||

|

Alternative 2 |

Socratic Dialogue

Socrates was an ancient Greek philosopher who developed a method of investigation through conversation involving deep questioning. Socratic dialogue involves an interlocutor or questioner who:

- Starts with a question: what is the philosophical problem we want to tackle? (For example, ‘Is it possible to be completely honest all the time?’)

- Leads us to discuss our own concrete, personal, everyday experience of this problem and asks critical, leading questions about that experience. Don’t be afraid to express your doubts and uncertainties. Do not use examples which are not from your own experience or which are hypothetical. Listen, be patient.

- Clarifies the deeper meanings that lie underneath this experience in a key generalisation, including the limitations of personal experience. This requires that you talk honestly and do not pass judgment. It also requires a certain level of openness and sensitivity to other people’s feelings.

- Strives to create a reasoned understanding that can be shared between the members of the dialogue, and a deeper level of knowledge than everyday or commonsense knowledge. What are the supporting arguments? What does the key generalisation presuppose or require? You need to respect other people’s points of view and be willing to change your view.

- Concludes with a statement of philosophical principle. Try to bring the conversation to a point of agreement—it’s not about one person in the conversation proving they are right.

Structured Academic Controversy

Structured academic controversy is a small-group discussion model, developed by David W. Johnson and Roger T. Johnson, to support students to gain a deeper understanding of an issue, to find common ground, and to make a decision based on evidence and logic.

In Experiencing the New students read/view and respond to appropriate background material on the selected issue; the background material should provide facts about the issue, as well as arguments favouring opposing views on the issue.

1. Pre-reading and reflection on the issue: Students are organised into groups of four, and each group is split into two pairs. One pair in a foursome studies one side of the controversy, while the second pair studies an opposing view. Partners read the background material and identify facts and arguments that support their assigned position. They prepare to advocate the position.

2. The presentations on the issue: Pairs take turns advocating their positions. Students on the other side make notes and ask questions about information they don’t understand. Next, pairs reverse positions. Each pair uses their notes and what they learned from the other side to make a short presentation demonstrating their understanding of the opposing view.

4. Responses to the presentations: Students leave their assigned positions and discuss the issue in their foursomes, trying to find points of agreement and disagreement among group members. Teams try to reach consensus on something; if they cannot reach consensus on any substantive aspect of the issue, they should try to reach consensus on a process they could use to resolve disagreements.

5. Responses by other teams: The class debriefs the activity as a large group, focusing on how the group worked as a team and how use of the process contributed to their understanding of the issue.

Taxonomy

Create a taxonomy which uses a tree structure to show how concepts are link to each other. Start with a ‘root’ or main concept, then show branches (child concepts) and sub-branches (children of children etc.). A taxonomy has more formal links than a Mind Map, and may be a way of visually mapping the terms in a glossary (as described in the ‘Conceptualising by Naming’ section, above). It can also be used in word study to explore prefixes, suffixes and root words.

Theory-Making

Write a theory using a language which describes underlying links and connections. Make the text clear enough for a well informed outsider to be able to understand something new. The theory may need to be supplemented by a taxonomy or a glossary. The theory could use language, image or mathematical symbols.

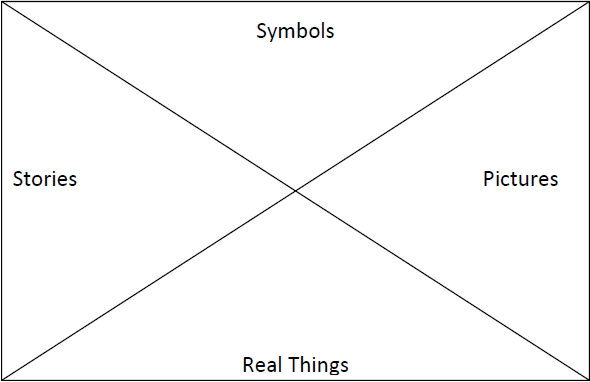

Thinkboards

Promotes conceptual understanding by enabling children to make connections. Design a large piece of card divided into 4 sections with each section displaying the same mathematical idea using different representations.

Four students are arranged around the board. They discuss and complete each section as it relates to their challenge. Responses are discussed in class. Think Boards can also be use in ‘Experiencing the known’.

‘What If?’ Scenarios

‘What if? Scenarios deepen understanding of a concept by exploring possibilities. For example:

- Naming: Name the features of the food chain.

- Theorising: What if you took out one link in the chain or added another? What if a drought killed one animal that was part of the food chain?