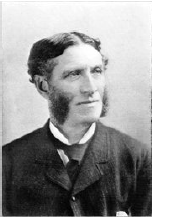

Matthew Arnold (1822–88) was one of 19th-century England’s most prominent poets and social commentators. He was for many years an inspector of schools, later becoming professor of poetry at Oxford University. Amongst his books, perhaps the best known is Culture and Anarchy (1869), in which he argues for the role of reading ‘the best that has been thought and said’ as an antidote to the anarchy of materialism, industrialism and individualistic self-interest. Arnold mounts a case in support of building and teaching a canonical body of knowledge:

There is a view [of culture] in which all the love of our neighbour, the impulses towards action, help, and beneficence, the desire for stopping human error, clearing human confusion, and diminishing the sum of human misery, the noble aspiration to leave the world better and happier than we found it—motives eminently such as are called social—come in as part of the grounds of culture, and the main and pre-eminent part. Culture is then properly described … as having its origin in the love of perfection; it is a study of perfection …

The idea of perfection as an inward condition of the mind and spirit is at variance with the mechanical and material civilisation in esteem with us … The idea of perfection as a general expansion of the human family is at variance with our strong individualism, our hatred of all limits to the unrestrained swing of the individual’s personality, our maxim of ‘every man for himself.’ The idea of perfection as an harmonious expansion of human nature is at variance with our want of flexibility, with our inaptitude for seeing more than one side of a thing, with our intense energetic absorption in the particular pursuit we happen to be following …

[T]he idea which culture sets before us of perfection—an increased spiritual activity, having for its characters increased sweetness, increased light, increased life, increased sympathy—is an idea which the new democracy needs far more than the idea of the blessedness of the franchise, or the wonderfulness of their own industrial performances …

[W]e have got three distinct terms, Barbarians, Philistines, Populace, to denote roughly the three great classes into which our society is divided [the aristocrats, the middle class and the working class, respectively] … All of us, so far as we are Barbarians, Philistines, or Populace, imagine happiness to consist in doing what one’s ordinary self likes. What one’s ordinary self likes differs according to the class to which one belongs, and has its severer and its lighter side … The graver self of the Barbarian likes honours and consideration; his more relaxed self, field-sports and pleasure. The graver self of one kind of Philistine likes business and money-making; his more relaxed self, comfort and tea-meetings … The sterner self of the Populace likes bawling, hustling, and smashing; the lighter self, beer. But in each class there are born a certain number of natures with a curiosity about their best self, with a bent for seeing things as they are, for disentangling themselves from machinery … for the pursuit, in a word, of perfection. To certain manifestations of this love for perfection mankind have accustomed themselves to give the name of genius; implying, by this name, something original and heaven-bestowed in the passion. But the passion is to be found far beyond those manifestations of it to which the world usually gives the name of genius, and in which there is, for the most part, a talent of some kind or other, a special and striking faculty of execution, informed by the heaven-bestowed ardour, or genius. It is to be found in many manifestations besides these, and may best be called, as we have called it, the love and pursuit of perfection; culture being the true nurse of the pursuing love, and sweetness and light the true character of the pursued perfection. Natures with this bent emerge in all classes—among the Barbarians, among the Philistines, among the Populace. And this bent always tends, as I have said, to take them out of their class, and to make their distinguishing characteristic not their Barbarianism or their Philistinism, but their humanity …

For a long time, as I have said, the strong feudal habits of subordination and deference continued to tell upon the working-class. The modern spirit has now almost entirely dissolved those habits, and the anarchical tendency of our worship of freedom in and for itself, of our superstitious faith, as I say, in machinery, is becoming very manifest. More and more, because of this our blind faith in machinery, because of our want of light to enable us to look beyond machinery to the end for which machinery is valuable, this and that man, and this and that body of men, all over the country, are beginning to assert and put in practice an Englishman’s right to do what he likes; his right to march where he likes, meet where he likes, enter where he likes, hoot as he likes, threaten as he likes, smash as he likes. All this, I say, tends to anarchy …

Now, if culture, which simply means trying to perfect oneself, and one’s mind as part of oneself, brings us light, and if light shows us that there is nothing so very blessed in merely doing as one likes, that the worship of the mere freedom to do as one likes is worship of machinery, that the really blessed thing is to like what right reason ordains, and to follow her authority, then we have got a practical benefit out of culture. We have got a much wanted principle, a principle of authority, to counteract the tendency to anarchy which seems to be threatening us.

Arnold, Matthew. 1869. Culture and Anarchy: An Essay in Political and Social Criticism. Oxford: Project Gutenberg. pp. viii, 7, 15–16, 41, 105, 108–110, 58, 67.