To tap into this literacy rich youth cultural activity, we developed a seven week poetry Unit that paired hip-hop texts with canonical works of poetry. The goal of the unit was to play on students’ heavy investments in hip-hop to create deeper understandings of school-based forms of poetry. We aimed to help students see the timelessness of the literary themes present in both canonical texts that they were mostly unfamiliar with and some of the music they listened to daily. We made explicit the fact that the literacy skills and knowledge that they exhibited in their interactions with hip-hop texts were not far removed from the skills required to succeed in analysis of poetry.

After pairing eight traditional poetry texts with eight rap songs, we divided our classes into groups of four or five students. Each group was responsible for preparing a class lesson on its pair of works. They were given relative autonomy for the form of their presentation, but each presentation was to have the following three elements:

- analysis of the literary themes of each work (we gave students a list of common themes but encouraged them to develop others as they saw them emerge in the work)

- comparative analysis of the two works (how are the works similar, how are they different, how do the authors use similar or different devices to deliver their message?)

- guiding questions for class discussion (we had modeled complex, open-ended questions throughout the year and encouraged students to design similar questions)

In addition to preparing the group presentation, each student was expected to prepare an analysis of the other seven poem/song pairings to participate in class discussions. We had worked hard all year on developing a classroom culture where student participation in dialogues about literary themes was normalized. This, along with the use of hip-hop texts that drew students’ attention, made the prospect of out-of-class preparation more likely, as the class came to enjoy challenging and broadening the literary analysis of their peers.

For the first two weeks of the unit, we spent class time going over poetic forms (sonnet, haiku, free form, prose) and poetic devices (rhythm, rhyme, meter, imagery, word choice, theme). We used examples from the eight pairings to teach these concepts, discussing with students their presence in music and traditional poetry. Students were also encouraged to bring passages from favorite songs or poems that displayed the ideas we were learning. During this time, students also began developing their poetry portfolios, writing poems that employed the concepts and forms that were discussed.

During the second two weeks of the unit, students continued developing their own poems while they worked in class with their groups and the teacher, preparing the analysis and presentation of their assigned pair. Class time was split between sharing and receiving feedback on their poems among peers and on preparing for their upcoming class presentations.

During the fifth and sixth weeks of the unit, each group was assigned one day to present its analysis and to lead the class in discussion about its pair. Presentations ranged from traditional stand-and-deliver approaches to more creative approaches where students brought in music videos and film clips or utilized interactive activities.

The remaining week-and-a-half was used for poetry readings. Each student was required to choose at least one poem to read in front of the class. These were often some of the most personally revealing and moving moments in the class. Putting the unit toward the end of the school year afforded many students the comfort level to risk sharing poems that revealed some of their most personal life experiences.

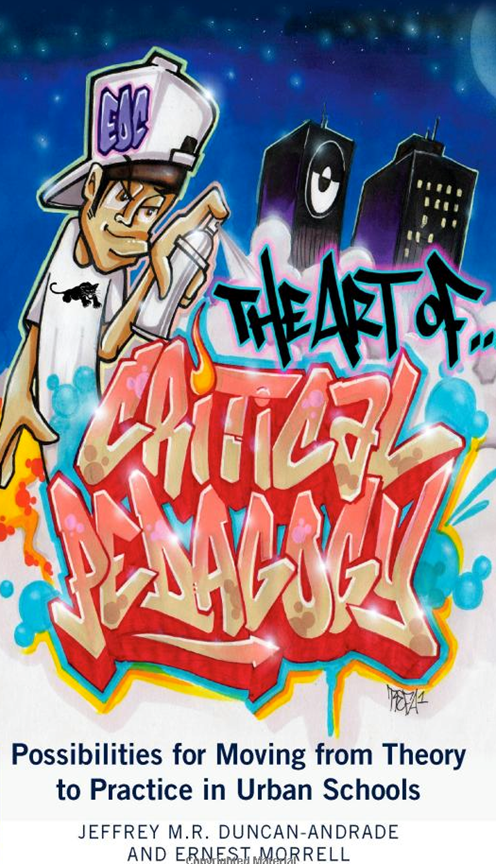

Duncan-Andrade, Jeffrey M. and Ernest Morrell. 2008. The Art of Critical Pedagogy: Possibilities for Moving from Theory to Practice in Urban Schools. New York: Peter Lang, pp.59-61. || Amazon || WorldCat