Until just recently one might have been forgiven for considering the ‘Reading’ debate to have been amicably resolved, with, at the end of the twentieth century, a negotiated consensus reached comprised of all sides in the debate agreeing on a balanced approach to the teaching of initial reading. However, the recent intervention of the House of Commons Education and Skills Committee with its report, Teaching Children to Read, and its advocacy of synthetic phonics, has once again brought the teaching of reading in UK schools to public attention. This paper seeks to provide an interesting comparative example of a UK literacy context where synthetic phonics is employed regularly and systematically. Thousands of British schoolchildren attend mosque schools on a daily basis where they learn how to read the Classical Arabic of the Qur’an. They are taught how to decode the text accurately and fluently using synthetic phonics methods. …

The pupils whose reading performance and behaviour feature in the study reported below share certain cultural characteristics that have a bearing on their reading development. Firstly, they are from an ethnic minority language community (Mirpuri-Punjabi) and learn English as an additional language in and outside of school. In this respect, they share similar characteristics to all minority language speakers when learning to read in English. They are sometimes less constrained by considerations of meaning when learning to read and can often be focused quite narrowly on accurate decoding. This is particularly the case when pupils are reading in a non-familiar script.

Secondly, these pupils are Muslims and regularly attend the local mosque school on a daily basis where they learn to decode accurately the Classical Arabic of the Qur’an. The method used in the mosque school is overwhelmingly a synthetic phonics approach.

The fact that these pupils learn how to read in Classical Arabic in an extremely intensive, and, it should be emphasised, successful, manner could, perhaps, provide a comparison when discussing the use of synthetic phonics in the teaching of initial reading in mainstream schools. …

… The reading of these pupils can best be characterised as one overly dependent on graphophonic strategies. To observe these pupils read is to witness often a competent skill in decoding English text accompanied by a lack of comprehension. [T]his is a problem when reading English, but within the context of reading Classical Arabic in the mosque school is perfectly acceptable. The aim of reading in the mosque school is the ever-increasing skill of accurate decoding. Reading for meaning does not play a major part in this literacy practice for the majority of children involved.

The experience of these children and their teachers as they simultaneously learn to read in Classical Arabic and in English, and, possibly, in Urdu—though in many UK Muslim communities where these three languages are used, it is the latter language that is under threat—can, perhaps, be illustrative of the effects on the reading process of children who have followed a precise and systematic programme in synthetic phonics, albeit in a different language. …

[T]here is little doubt that the method of teaching reading employed in the mosque school is an overwhelmingly successful one. Given the limited aim of developing children into competent and accurate decoders of a written script over the course of a five or six year period, roughly equivalent to Key Stages One and Two, the majority of children go on to attain the expected standard when they finish, usually at the age of 12 or 13. They are able to decode the Qur’an (a book in length somewhere between the Old and New Testaments) from beginning to end and read and memorise enough Classical Arabic to carry out their daily prayer and take part in other ritual practices such as Friday Prayer. Many children will have memorised a significantly greater amount than this. …

The basic method for Qur’anic instruction is based on a look-listen-repeat model of learning. The children begin with the 26 letters of the Arabic alphabet and learn these firstly as names (see Foulin, 2005). For example, the first letter of the alphabet is called ‘alif and the child begins by learning the name ‘alif. The name is loosely connected to the sound the letter might represent.

Children will then go on to learn the sounds of the letters so that ‘alif becomes {a}, {i} or {u} depending on the vowelling that accompanies it. Unlike the English alphabet, the Arabic alphabet is made up nearly exclusively of consonants, or semi-consonants, and vowels are indicated by diacritic marks above or below the letters. A child will learn these consonants and then proceed to learn each letter with, initially, the three basic vowel sounds, {a}, {i} and {u} indicated by these diacritic marks.

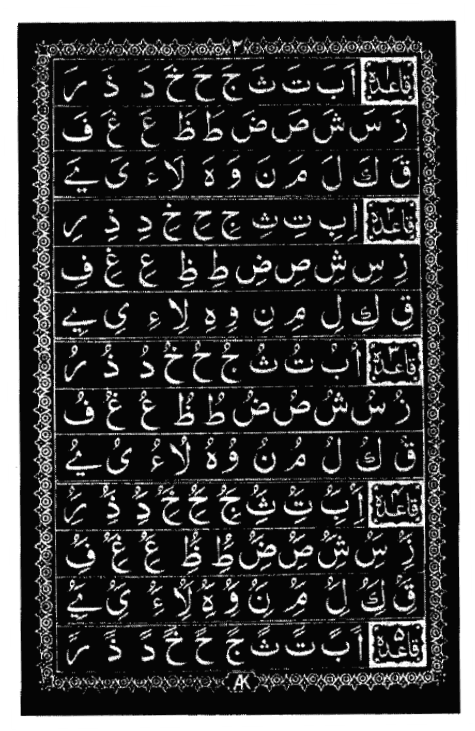

Each child will repeat and memorise the letter-sound correspondences until the teacher considers them ready to move onto the next stage. This will be to combine these consonant plus vowelling units with others to form syllables. This stage is then followed by words which can be real or nonsense words. This then leads to reading phrases that by now are all meaningful and recognisable from the Qur’an or other parts of the scripture, such as the kalimahs. The kalimahs are a series of utterances that encapsulate the fundamental beliefs of the Muslim and, along with learning the words of prayer and recitation of the Qur’an, constitute the main learning activity in the mosque. The central kalimah is ash-hadu a-laa ilaaha ill-Allah, ash-hadu ana Muhammada-r-asool Allah which means ‘I testify that there is only one God and that Muhammed is the Messenger of God’. The final stage in this preparation for reading the Qur’an itself is the reading of complete verses that occupy the last few pages of the Qaidah. Alongside this growing competency in decoding the child also learns some basic principles about recitation including the features of correct sound formation and phrasing.

The Qaidah is a short primer of the Arabic reading system. It usually contains between 10 to 40 pages and begins with the alphabet on the first page followed by subsequent pages that follow the sequence described above. Occasionally, children are given a single page containing the alphabet only and this can be obtained in plastic so that the page remains intact after generous use by young hands. …

The teacher makes the decision as to when a child is ready to move onto the appropriate next stage. Children are aware and sensitive about where they might have got to in their learning of how to read the Qur’an and are always ready to declare, or boast, where they might have reached. Similarly, the teacher will decide when a child has reached the end of their course of instruction and will either inform the parents that there is no longer a need for their son or daughter to attend or that he or she would benefit from a more advanced course in memorisation that always comes later. It is clear that this is a bottom-up approach to reading where all instruction on the part of the teacher, and all effort, on the part of the learner, are targeted at developing accurate and fluent letter-sound correspondences, moving from a mastery of single letter-sound correspondence to the build up of syllables and words. …

[T]he synthetic phonics approach employed for the teaching of reading Classical Arabic in the mosque school is a tried and tested method that has altered little either through the centuries or across many continents. The methods used to teach young British Muslim boys and girls differ hardly at all from the methods employed, say, in Morocco (Wagner, 1993) or in Indonesia (Baker, 1993). Despite other issues regarding pedagogy and curriculum in the UK mosque school that may be debated within the community (see Rosowsky, 2004), the core literacy activity is an efficient and successful one. Children arrive at the age of 11 or 12, and many much earlier than this, with a competent and developed ability to decode accurately the Classical Arabic text of the Qur’an. They have developed an efficient and fluent skill in creating sounds from graphical representations on paper. They have moved from letter names, to letter sounds, to syllables, to words, to phrases and sentences, until they can read, or decode, the complete text of the Qur’an.

As far as the mosque school is concerned, for the majority of children, this is enough. There is no accompanying programme designed to match this decoding with the meaning of the words and verses. In a very real sense, one can see how difficult this would be anyway. The Qur’an is in Classical Arabic, a language the children, or their parents, do not speak, and, moreover, is a version of Arabic that represents a style and period very distant even from the modern Arabic spoken and understood in Arabic-speaking countries today. It is possible, one might imagine, for some children to follow a course in comprehension, akin to that of English-speaking children studying Latin, though even then, it would be far from a good working understanding of the text. The children, therefore, are provided with this developed decoding ability that allows them access to the Qur’an, albeit in a limited manner, and to other texts linked to their lives as Muslims.

Rosowsky, Andrey. 2005. “Just When You Thought it Was Safe: Synthetic Phonics and Syncretic Literacy Practices.” English in Education 39:32-46.