Reggio Emilia is an example of a dialogic learning environment that connects closely with community setting and draws upon a variety of knowledge sources:

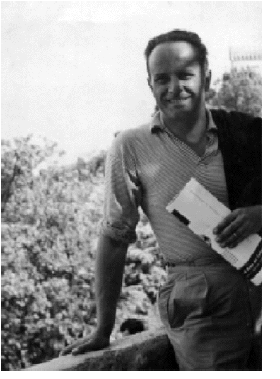

At the end of the Second World War, a group of parents in the Northern Italian town of Reggio Emilia established a network of municipal preschools. Sensing their enthusiasm and the potential to innovate, leading Italian educator, Loris Malaguzzi (1920–94), soon became involved. The approach to early childhood learning that emerged is now called the Reggio Emilia Approach. Its key features include: a mix of self-selected activities and project oriented curriculum in which teachers work with learners to solve a real-world problem (see the long jump example below); close parental involvement; two teachers per class; students staying in the same group with the same teachers for three years; a carefully crafted physical environment of learning; an atelierista or a support teacher with arts training who works with teachers in curriculum planning, resource development and documentation; and a systematic approach to professional learning in which teachers observe each other and engage in cycles of reflective/research practice. Here is Malaguzzi describing the Reggio preschools:

To start with, then, there is the environment. There is the entrance hall, which informs and documents, and which anticipates the form and organization of the school. This leads to the dining hall, with the kitchen in view. The entrance hall leads to the central space, or piazza, the place of encounters, friendships, games, and other activities that complete those of the classrooms. The classrooms and utility rooms are placed at a distance from but connected with the central area. Each classroom is divided into two contiguous rooms, picking up one of the very practical suggestions of Piaget. His idea was that to allow children to be with either teachers or stay alone; but we use the two spaces in many ways. In addition to the classrooms, we have established the atelier, the school studio laboratory, as a place for manipulating or experimenting with separate or combined visual languages, either in isolation or in combination with verbal one. We have also the mini-ateliers next to each classroom, which allow for extended project work. We have a room for music and an archive, where we have placed many useful objects both large and small, and non-commercial, made by teachers and parents. Throughout the school the walls are used as spaces for both temporary and permanent exhibits of what the children and teachers have created; our walls speak and document.

The teachers work in co-teaching pairs in each classroom, and they plan with other colleagues and families. All the staff members of the school meet once a week to discuss and broaden ideas, and they participate together in in-service training. We have a team of pedagogisti to facilitate interpersonal connection and to consider both the overall ideas and the details. The families meet by themselves or with the teachers, either in individual meetings, group meetings, or whole school meetings. Families have formed an Advisory Council for each school that meets two or three times a month. The city, the countryside, and the nearby mountains serve as additional teaching sites.

Thus, we have put together, a mechanism combining places, roles, and functions that have their own timing, but that can be interchanged with one another in order to generate ideas and actions. All this works within a network of cooperation and interactions that produces for adults, but above all for the children, a feeling of belonging in a world that is alive, welcoming, and authentic.

Project work is one of the key aspects of the Reggio experience, adventures that can last a week or much longer. Teachers work with children to decide objects of study, how they will be studied and the means of representation they will use—what Malaguzzi called the ‘hundred languages of children’, or acts of symbolisation including movement, drawing, sculpture, drama, music and writing.

First the four children, Lorenzo, Augusto, Stephania, and Silvia, ages 5 ½ to 6 years old, sought to understand the cultural form of the Long Jump. They looked at photographs … and reminisced about their own rather meager experiences. The children also observed each other jump … and returned many times to discuss their knowledge and assumptions … [P]hotographs and the teacher stimulate this verbal outpouring but the details are missing. There is much to be understood.

[L]earning and the construction of knowledge has a mental course of its own, full of mental replays, reflection, and representations … These mental cycles repeat many time within any project. It follows that cycles of symbolization is an apt descriptor of this process … A single cycle is defined by a common problem, such as the relation between running space and landing space. Within a single cycle the children confront and discuss a problem using a variety of symbol systems, some invented, some conventional. Their motivation for using and inventing symbols is (a) to gain better purchase on their own understanding of something, and (b) to present that understanding clearly to others.

After looking at the photographs the children were encouraged to make a pencil sketch of the long jump event … The drawings help children look at each other’s thinking. All children can see and comment on a drawing. A drawing is a commitment to specifics. The teachers want the children to make these commitments explicit so that specific agreements or disagreements can occur.

Both Augusto and Lorenzo laid out a rather short run-up space and proportionately much longer landing space … This relation will be reconstructed when children actually go outdoors to run … and to lay out the track … But the initial drawings bring relative distance to consciousness and increase the probability that children are testing ideas when they make the tracks outdoors. This is how a cycle of symbolization works to support deeper learning.

Edwards, Carolyn, Lella Gandini and George Forman. 1993. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex. pp. 56–58, 174–176. || Amazon || WorldCat