Transformative education: Towards New Learning

If the pace of change in schools seemed glacial over the course of the 20th century, there are reasons to believe that it is about to quicken in the 21st. Some of the rea- sons for this may be attributed to external factors. It is nearly impossible for schools today to avoid addressing new technologies, globalisation, diverse classrooms, the changing nature of work and citizenship, and the shifting dimensions of human subjectivity, identity and personality. Schools increasingly have to speak to these broader social realities simply in order to remain relevant.

See Bill Gates on American Schools.

Among the changes educators face, some come from the changing sensibilities of students and teachers. In the developed world at least, today’s children and young people come from the video game, MP3 and digital television generation. They are the products of child-centred upbringing in a consumer society. They will simply not put up with traditional classrooms the way earlier generations did, even if at times these older generations only barely tolerated them. Nor will today’s teachers put up with working environments that challenge their professionalism by dictating the script of what they will teach, when they will teach it and how they will teach it.

See Transformative Education Case Studies.

Meanwhile, new possibilities for teaching are also opened up by the new, digital media. In its initial phases, e-learning has often appeared to replicate the worst of old teaching. But a newer phase of e-learning is creating new learning spaces in which teachers and learners challenge and transform the social relations of traditional classrooms and didactic pedagogies.

Educators need to be keen observers of change. This is the only way we can keep our teaching, and our schools, up to date and relevant. But, more than this, we must be agenda-setters and change-makers. We have the power to transform our classrooms and our schools. As we embark on these transformations, we also make our own contribution to the transformation of the broader society. Better learners will better contribute to the making of a better society.

If we were to choose a single word to characterise the agenda of the New Learning, it is to be ‘transformative’. New Learning, for us, is thus not simply based on a reading of change; it is also grounded in an optimistic agenda in which we educators can constructively contribute to change.

If knowledge is indeed as pivotal in contemporary society as the ‘new economy’ commentators and politicians claim, then educators should seize the agenda and position themselves as forces of change. Not only is the education of the near future likely to drift further away from its roots in the industrial era. So it should. And ‘should’ means that we have a professional responsibility to be change agents who design the education for the future.

After a century of progressivist attempts to improve on didactic education, the ‘New Learning’ needs to be authentic and more; it should also be ‘transformative’. Being authentic may produce a better fit between education and society, but leaves society fundamentally the way it is. It sets out to reflect the realities of the world more than to change them. It does not necessarily move the learner in terms of intergenerational mobility or life trajectory. Transformative education builds on many of the insights of authentic pedagogy, to be sure, but ups the ante. Its aims are no less than to change the life chances of the learner and to change their world.

The transformative education that we identify is emergent. Nowhere are we there yet, but we can see many symptomatic signs of change. Transformative education is an idea that builds upon and extends the insights into the nature of learning and the role of education in society to be found at moments in both didactic and authentic education, while attempting to move beyond their main limitations. It is something that recognises the educational legacies of the past in order to design better educational futures. Transformative education is an act of imagination for the future of learning and an attempt to find practical ways to develop aspects of this future in the educational practices of the present. It is an open-ended struggle rather than a clear destination, a process rather than a formula for action. It is work-in-progress.

The third part of each chapter of this book describes transformative dimensions of our ‘New Learning’ proposal. The idea of transformation stands in contradistinction to, at the same time as it builds upon and develops, the heritage practices of didactic and authentic education. In one sense, this is an exercise in the broad integration of ideas across the science of education, articulating a theoretical framework for the discipline.

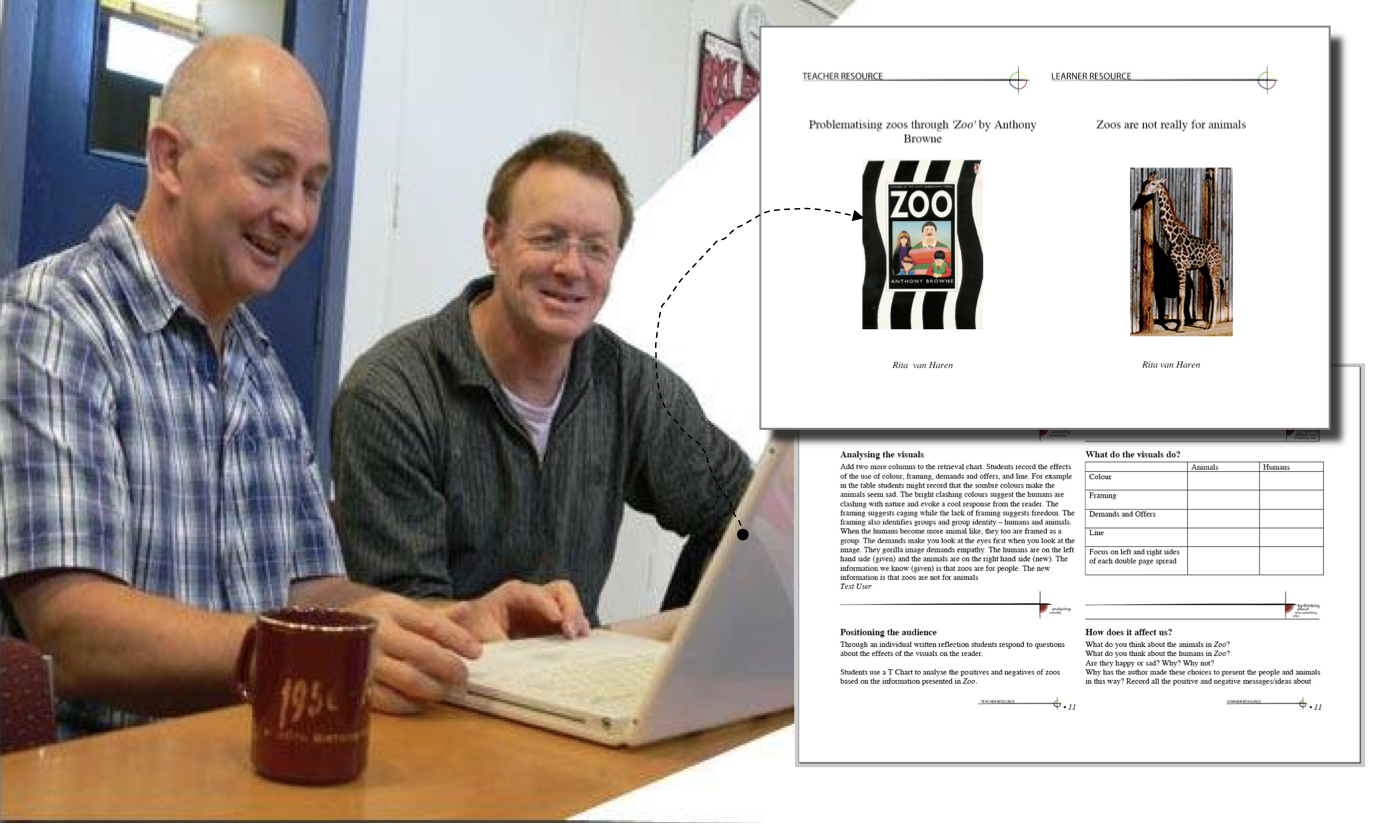

This exercise, however, is also a very grounded and practical one. As educators – teachers and people who have worked with teachers in training and in-service professional development – we have ourselves struggled with the practical question of the design of our educational futures in the various projects with which we have been involved, from Social Literacy in the 1980s, to Multiliteracies in the 1990s, to Learning by Design in the 2000s. The ideas of New Learning and transformation are, for us, not just schematic and theoretical. They are vividly and insistently practical, the stuff of what you do with your learners on Monday morning.

See Kalantzis and Cope, A Learning Journey.

So what do we think a transformative education might achieve? At its best, trans- formative education embodies a realistic view of contemporary society, or the kinds of knowledge and capacities for knowing that children need to develop in order to be good workers in a ‘knowledge economy’; participating citizens in a globalised, cosmopolitan society; and balanced personalities in a society that affords a range of life choices that at times feels overwhelming. It nurtures the social sensibilities of a kind of person who understands that they determine the world by their actions as much as they are determined by that world. It creates a person who understands how their individual needs are inextricably linked with their responsibility to work for the common good as we become more and more closely connected into ever-expanding and overlapping social networks.

Make of this what you will. It could be that you see it as a sensible conservatism, sensible for being realistic about the contemporary forces of technology, globalisation and cultural change. Or you could see it to be an emancipatory view that aspires to make a future that is different from the present by addressing its many crises – of poverty, environment, cultural difference and existential meaning, for instance. In other words, the transformation may be pragmatic (enabling learners to do their best in the given social conditions) or it may be emancipatory (making the world a better place) or it may be both.

What follows is an outline of some aspects of the landscape of New Learning and its transformative view of education. Some of this may be happening now. Some looks likely to happen. Other things may happen sooner or later.

Dimension 1: Architectonic

Imagine this scenario: what if students could do their work anywhere, not just in the classroom to which the school timetable has sent them, but in small syndicate rooms, in the library, in somebody else’s classroom, in locations out in the community where knowledge is made and used (a local library, a gallery or museum, a workplace, a community organisation) or in a group of students who decided to work at one of its members’ homes? What if they are connected with teachers, information and other learners globally and locally, seven days a week, 24 hours a day through any number of web-enabled devices?

Impossible, you might say. What about the teacher’s duty of care? How would the teacher know what each student was doing? Where they were? What they were exposed to? To which we might respond, nowadays you can know where every child is, no matter where they are, and as well as any teacher did, perched up on their little platform surveying the traditional class. Every child in this scenario has a mobile phone, a reading and writing tablet, or a personal computer, with global positioning system facility that tells you exactly where they are within a range of error of one metre. (This happens to be about the same margin for positional error as in the traditional classroom.) It means they can talk to you and you can talk to them. And you can know exactly what they are doing because they are constantly committing their work to a ‘cloud’ web server-based content sharing and messaging system that wraps around this work. Every message is collected, and this can tell every little step in the developmental ‘story’ of that work. The teacher can just as easily as ever ‘see’ what the learners are doing, and automated systems can alert them when students stray beyond agreed locations, or outside of negotiated task parameters. This is particularly helpful in the case of jointly constructed student work, because it is now possible to see exactly who has done what in a collaborative piece of work.

This is a new communications design, and one that means that students do not have to be co-located within a classroom. In fact, the physical classroom for thirty kids and one teacher may become an anachronism, a throwback of industrial-era schooling.

See The MET: No classes, no grades and 94% graduation rate.

What on earth are we going to do with all those old school buildings now? Authentic education made the best of heritage infrastructure, unbolting the desks from the floor and rearranging the rooms in ways that had never been envisaged by their architects. Up to a point, we can knock down the internal walls in old schools and put up new ones that divide the space in different and more varied ways. We can set up wireless connectivity in the school so the dominant communications dynamic is not room-by-room, one-voice-at-a-time audio. But there may be a limit to how far we can go with this. And when we reach this limit, we might need to build completely new schools in which spaces are multifunction, multipurpose, flexible and varied.

See Class Work.

If we trace the trends to their logical conclusion, sometimes it may be just too hard to redesign the old schools. In these cases, we might have to regard the old buildings as a real-estate problem rather than an educational one. Perhaps developers with some flair for recycling might turn them into community drop-in centres, apartments or marketplaces and so help fund the building of brand new schools for the future.

Dimension 2: Discursive

Traditional teaching discouraged lateral communication between students. The New Learning thrives on enormous amounts of lateral communication between learners: face-to-face talk; Internet and mobile telephony; online chat; instant messaging; email and messaging around text, image, sound and video in content creation and sharing environments. In the old classroom this amount of lateral interaction would have turned out to be unmanageable ‘noise’. The teacher could not possibly have listened to it all at once. The stuff that would have been noise is now ‘visible’, as the teacher selectively views interactions and intelligent computer ‘agents’ automatically monitor student interactions and send the teacher alerts if anything seems out of order. It also allows for multiple languages, multimodality, invented discourses and special communication means for those with disabilities, thus expanding exponentially access and potentials for expression of meaning.

In this environment, the orienting axis of communications has changed from vertical to lateral. Learners become teachers of each other. They give each other structured feedback. There is a certain kind of levelling of the roles of teacher and learner. They are not, of course, equals in terms of teachers’ greater responsibility for building scaffolds for student learning based on their deep professional understanding of the science of education, nor in terms of their respected positions as bearers of authoritative knowledge, nor in terms of their duty of care to ensure that learning environments are welcoming and safe. However, there is a subtle but important dis- cursive shift from the teacher’s authoritarian stance in the traditional classroom to their authoritative position in the New Learning. The old teaching discourse of command becomes the new learning discourse of dialogue.

Along the way, the neat mathematics of teaching changes. It does not always have to be one teacher to thirty or so students. Sometimes it will be one to one, other times one to a small group, other times one to one hundred (when lots of learners access an online resource created by a teacher, or watch a teacher’s video, or listen to a large group presentation, either live in-person or live online). Still other times it will be two or more to however many – in the case of team teaching or jointly created learning resources. The overall teacher–student ratios might stay the same. (It is hard to imagine that resourcing for education will suddenly improve, although educators should continue, insistently, to make the claim that a knowledge economy is only as dynamic as the investment it is prepared to make in education.) It’s just that the economies of scale may be much more variable. The average of one to thirty does not necessarily have to change. It just no longer means that this has to be the same one to the same thirty, or always in the one place and always at the one time. Alternatively, if the human resources of educators are to be used more efficiently (for instance, learners only accessing teachers when they are needed, otherwise working in crafted, self-paced learning environments, learning with peers and learning in community) there may be scope to increase teachers’ salaries to a significant extent, with or without substantially more resources overall having to be devoted to education.

See Children Learning on their Own.

Dimension 3: Intersubjective

Authentic education went some of the way to change the intersubjective balance of agency between teachers and learners. It granted learners a significant role in constructing their own knowledge through experiential-, inquiry- or activity-based learning. But the teacher was still very much in command and the systems of reward and punishment remained little changed. At best, individual learners could do their own work, at their own pace and in their own way, perhaps with some support and assistance from a group.

The New Learning places an additional premium on learner engagement, starting with the careful identification of learner needs, identities, expectations, aspirations, interests and motivations. If the learner fails to engage with these raw materials of subjectivity or agency, they will not learn. Critically, however, these things are not individual (the ‘activity’ notion in authentic education), but the stuff of social relationships (hence an ‘interactivity’ notion in the New Learning). Successful learning occurs in a social context that affirms the learner’s identity and in a social setting that supports their interests, values, perspectives and contributions. The deepest learning occurs in an environment of reciprocity and sociability. This is a context in which learning is a matter of negotiation rather than imposed subject contents, and where students are meaning makers as much as they are meaning receivers. It is also a context in which new incentive and evaluation systems need to be designed into the learning experience – work that is truly interesting and engaging from the learner’s point of view; collaborations with others that include the social expectation that you should give your all; communication of the work to other learners, parents and the broader community, perhaps through web-based portfolios; and assessment of published portfolios by qualitative review rather than a single mark and by peer review rather than only by the teacher.

Above all, these new intersubjective relations mean that teachers need to let go of the old position of command they have become so used to holding. This is some- times intimidating for those who were schooled in the old teaching or even some forms of authentic education. Teachers here need to see themselves more as collaborative researchers, designing and tracking, purposeful, transformative interventions. This will require supportive networking and professional collaborations: with other teachers, community partners and with learners themselves. Allow the learners to take greater responsibility for their learning. Allow that they might know, or be able to find out, things that you, the teacher, would not necessarily know. Allow that trust will breed responsibility. And allow that things will go wrong, but that the balance of benefit as measured on a scale of the effectiveness of learning, will be worth it.

See Discovery 1, Christchurch.

Dimension 4: Socio-cultural

In the New Learning, learners’ different attributes are fundamental. Effective learning will not occur unless the professional educator finds a way to deal with these differences. They are myriad: material (class, local and family), corporeal (age, race, sex and sexuality, and physical and mental characteristics) and symbolic (culture, language, gender, family, affinity and persona). And they are profound, representing at times huge gulfs between one learner and the next – in values, style, affect, sensibility and disposition. We discuss these differences in detail in Chapter 5.

In response to these differences, the New Learning spends time finding out about learners’ prior experiences, interests and aspirations. It allows that different learners can be working on very different things at the same time. It allows for different learning habits: some learners will feel more comfortable learning by immersion in experience, willing to wait for a ‘big picture’ view to emerge; others will want to start with the abstract map of the big picture, then try to fit the experiential pieces into that map. New Learning identifies and negotiates alternative learning pathways to common goals, appropriate to students’ capacities as formed by prior learning, meeting their needs and satisfying their interests.

Getting beyond the subtle and often not-so-subtle homogenising and assimilationist tendencies of didactic and authentic education, the New Learning is inclusive (no child left unbelonging) and pluralist, respecting and building upon the personal experiences and cultural knowledge each learner brings to learning. It fosters the sensibilities and develops the skills for affirming one’s own and others’ identities and negotiating differences in order to succeed. It is locally grounded, yet outward looking towards a global context.

Dimension 5: Proprietary

In authentic education, the classroom is still a relatively private, enclosed space. Learners mainly do their own, private work, albeit sometimes with higher levels of individualisation and self-direction than was the case in the didactic teaching. In the New Learning, the physical walls are broken down if not literally then metaphorically.

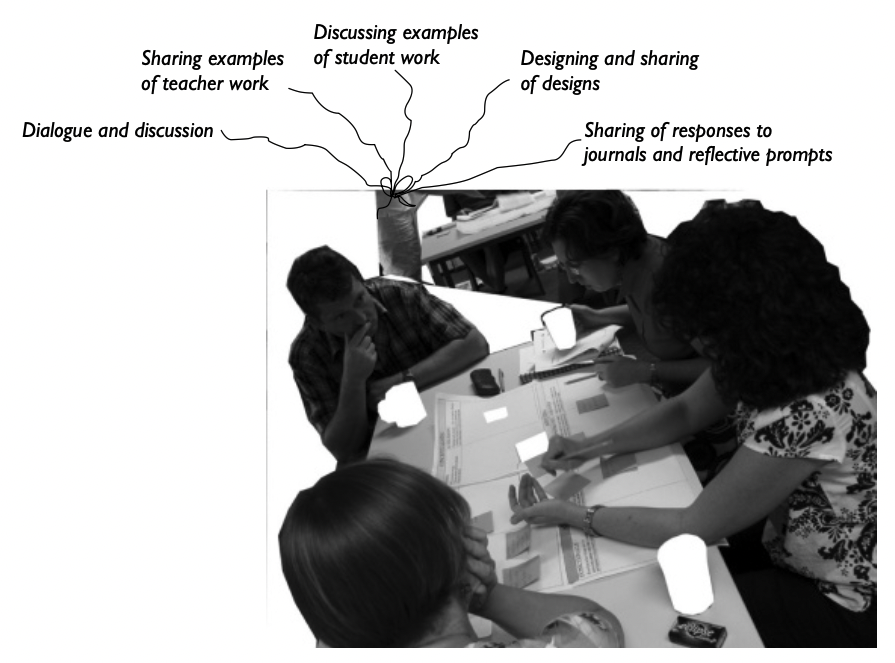

No longer ‘lone rangers’, teachers work together as members of an integrated community of professional collaborators. They work closely with other teachers in team teaching. They document, publish and share the lesson plans and learning resources they have developed. They work with aides to assist students with identified needs requiring a specialist outside of the teacher’s range of expertise. They involve parents. They involve community experts – on site, online, or hosting learners off site – who can make a contribution to the learning.

The teacher of the old, cloistered classroom becomes a thing of the past. No longer is the classroom an enclosed, private, even secret, space. What the teacher does with ‘their’ class is no longer simply a matter of spoken words that disappear into the ether the moment they are uttered. They create their learning designs in accessible new media spaces, in which learning interactions are more visible and can be incidentally recorded. Now they can become a different kind of worker, a collaborative professional whose knowledge and experiences are always shared and, for this reason, complemented and corroborated by other professionals. Their every pedagogical word is transparently on the record and open to scrutiny – the learning sequences they have created for their learners, the conversations with the students around their work.

Student learning activities become more open and collaborative, too. In authentic education, student learning may be more individualised and self-paced than in didactic teaching. Even when a student is doing a complex, multidisciplinary self-directed project or assignment, it still mostly has to be ‘your own work’. (‘Don’t copy’ and ‘it’s a problem if your parents help’ ... too much or too obviously, that is.)

There’s still a place for individualised activities and private learning spaces in the New Learning. That’s not because individualised learning is an end in itself. In fact, making this an end itself (‘my marks’ for ‘my work’) seems to encourage students to play the system by cheating or plagiarising. The audience for the meaning maker in individualised learning should not just be the audience of one, the assessing teacher who gives the work a ‘54’ (which we get to know means ‘passable but not very good’) or a ‘76’ (‘pretty good but not brilliant’). Rather, the audience for every student when they make meanings should be other learners (the class as a learning community), parents and the wider world. This is what happens when the work is published to the Internet, simultaneously into the learner’s own portfolio and the class ‘bookstore’. This way, private vertical communication flows are replaced by lateral, public, community oriented flows. Learners speak to an audience of many. If you dare to plagiarise, it is not just the teacher you are trying to deceive, but your peers and the world – and it’s more likely your peers who will find you out. Easily accessible digital text makes it easier to plagiarise, and also harder to get away with, because there are more people who might pick it up and because the sources are more public and easily traceable.

Beyond individualised teaching, the New Learning opens up space for collaborative learning, reflecting the changing shape of today’s workplaces and learning communities beyond the formal institutional settings of education. Collaborative work is produced in pairs or small groups; students thus learn how to think and act as team players. The collective outcome is greater than the sum of the individuals’ contributions. So, the learners become good communicators, good readers of others’ differences, good at negotiating, good at compromising and good at producing knowledge that is jointly owned. In didactic teaching as well as in authentic education, collaborative work was hard to manage for the most practical of reasons. How could an assessor ever know whose contribution was whose, without watching every learner’s every move? With the versioning, messaging and tracking systems of today’s networked content management environments, however, it’s possible to know exactly who did what and when. If you’re not pulling your weight, it will be obvious to the other learners and the teacher.

The nice twist is that, as soon as learners become good at collaborative learning, they start to do individualised learning in a new way. If you’re new to something, you find expert sources (peers, specialists, published information) who will give you explicit support and advice (we call this ‘assisted competence’ – see Chapter 9). If you’re comfortable with something and think you can figure it out more or less for yourself, you’ll be confident enough to use, assemble and acknowledge a variety of other sources of information and inspiration (‘autonomous competence’ – also Chapter 9). Soon, even individualised activity becomes collaborative. This is how the active learning processes of authentic education turn into the interactive learning processes of transformative education.

See Ivan Illich on ‘Deschooling’.

Dimension 6: Epistemological

In didactic teaching, teachers and textbooks told. They expounded, bit by laborious bit, the facts and theories they thought learners needed to know in order to master a discipline. Transformative education encourages ways of thinking based on a different understanding of how knowledge is most effectively and powerfully made, particularly in today’s social settings and those of the conceivable future. The base point is not teacherly or textbookish regurgitations of knowledge, but working with real- world texts, issues, ideas and problems. Students research the facts, test them and corroborate them. Indeed, facts only become facts when they have passed a number of tests – of apperception (how well have you observed?), plausibility (do the facts make sense?) and applicability (do they it with other facts and do they work?). These tests are for the student to apply, never to take a single source at its word and never to accept that a fact is a fact just because someone says so. Then, putting the facts together, hypotheses are developed, and theories are created inductively and then tested deductively against the facts. Thus, as we argue in greater detail in Chapter 8, learners become reflexive knowledge makers rather than knowledge receptors. This way, the disciplines become not so much bunches of facts and theories, but approaches to knowledge creation: scientific, historical or literary, for instance. And knowledge is constructed from multiple sources, based on variable perspectives, knowledge orientations and approaches to problems.

See Ken Robinson on How Schools Kill Creativity.

Underlying this is a profound shift in the direction of knowledge flows. Learners become co-designers of knowledge, developing habits of mind in which they are comfortable members of knowledge-producing and knowledge-sharing communities. And teachers build learning experiences that engage with learner subjectivities, developing and negotiating learning scaffolds that can be customised for different individual learners or groups of learners and extend learners. In so doing, they build on and extend learners’ identities and senses of destiny.

Along the way, discipline boundaries may need to be blurred, to the extent even of breaking out of the constraints of the old, subject-divided timetable. The New Learning becomes increasingly interdisciplinary, requiring deeper engagement with knowledge in all its complexity and ambiguity.

If we are to avoid the difficulties of the ‘crowded curriculum’ or the ‘shopping mall curriculum’, we may have to re-conceive the core of learning or ‘the basics’. We may even need to move towards more general and more comprehensive education, with just a few key areas, such as technology (science, mathematics, applied sciences), commerce (enterprise, innovation, working together) and humanities (cultural understandings, capacities for intercultural interaction and boundary crossing). Even though this is a moment of technical specialisation, change and diversity in all areas of knowledge and human experience, it may well be that formal education needs to become more centred and more focused on a few core areas of learning. Perhaps, each of these core areas should be studied at a higher level of generality than the traditional subject areas, should be relevant to a broad range of students with quite different life aspirations, and should be applicable in very different contexts. This may prove to be the essence of a ‘new basics’.

Finally, the source of valid knowledge is no longer primarily linguistic as it was in the heritage practices of didactic teaching and, even more narrowly, the written word. It is also multimodal, where the visual (diagram, picture, moving image), gestural, tactile and spatial are considered to be just as valid knowledge sources as writing. This reflects the deeply integrated, synaesthetic meanings of our contemporary communications environment (Kalantzis and Cope 2012). Learners, moreover, can build and represent knowledge using a variety of meaning modes and mixes of mode. Why should a diagram be of less knowledge value than a theory-in-words? Or a documentary video of less value than an essay?

Dimension 7: Pedagogical

Didactic education focused on fixed content knowledge: undeniable facts and theories to be applied. This knowledge was supposed to last for life. Applied today, this kind of education becomes instantly redundant. Knowledge today is constantly changing, and particularly so in areas of dramatic social transformation, such as computing, biotechnologies, identities/sexualities or socio-historical interpretation. Indeed, old disciplinary approaches often foster rigid ways of thinking that are counter-productive for the workers, citizens and persons of today and the near future.

The New Learning is less about delivering a body of knowledge and skills that will be good for life and more about forming a deeply knowing kind of person. This person will be aware of what they don’t know, capable of working out what they need to know and be able to create their own knowledge, either autonomously or in collaboration with others.

In the New Learning, learners not only become creators of knowledge. They also represent the fruits of their creativity to each other. Their learning becomes a source for other learners. Knowledge sharing and collaborative learning are the glue that binds together collective intelligence.

As much as they develop disciplinary or content knowledge, they also develop knowledge about their knowledge making, and learning about how they learn. These habits of mind are often called ‘metacognition’: thinking about thinking alongside the pragmatics of thinking. This makes thinking all the more powerful. Metacognition entails one’s own thinking processes, consciously developing knowledge strategies and continuous self-monitoring to reflect on one’s learning. In these ways, not only do learners become co-designers of knowledge, they also become co-designers of learning.

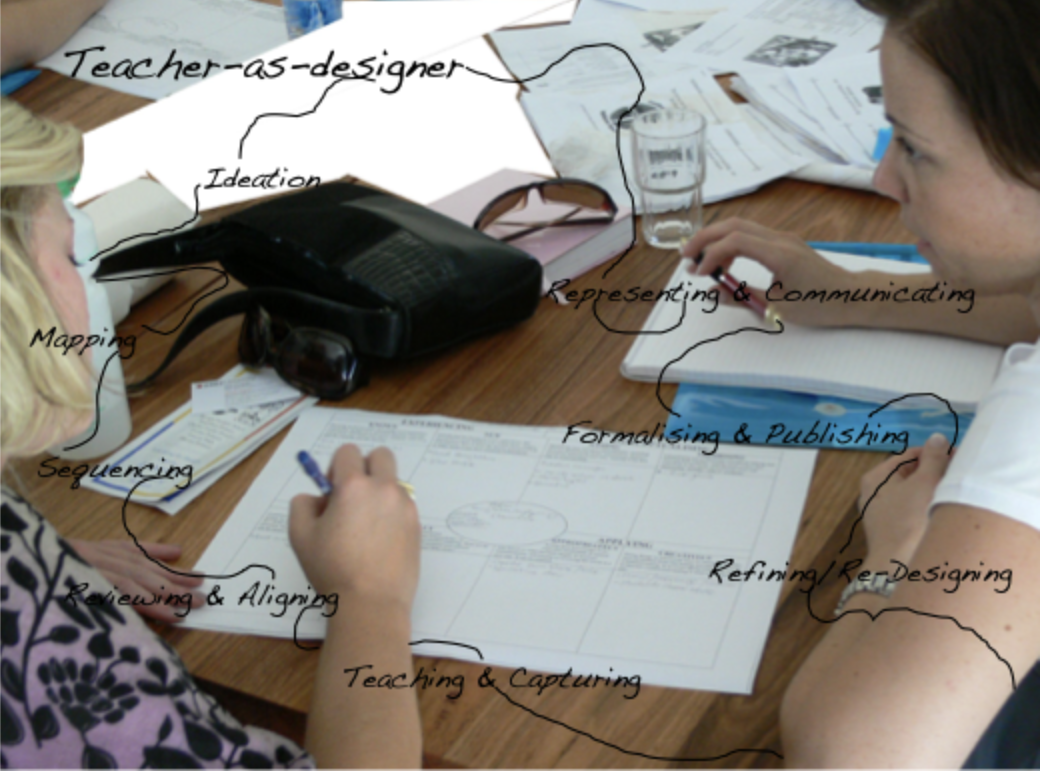

At the same time, the role of the teacher-as-pedagogue also changes. No longer do they stand and deliver. No more are they primarily a font of disciplinary knowledge. Their role expands as they are now not only knowledge experts but also designers of knowledge-making environments, builders of learning scaffolds, managers of student learning and researchers of learner performance.

Dimension 8: Moral

Education always creates ‘kinds of persons’. Didactic education forms people who have learned rules and can be relied on to obey them; people who take answers out to the world rather than regard the world as an ever-unfolding series of problems to be solved; and people who think they have ‘correct’ knowledge in the private spaces of their heads. As we argue in the chapters that follow, these orientations to the world are inadequate to the demands of changing work (Chapter 3), citizenship (Chapter 4) and personhood (Chapter 5). The New Learning imagines a kind of person who is able to navigate constant change and deep diversity, learn as they go, solve problems, collaborate, innovate and be flexible and creative. This kind of person will not be traumatised by change. They will not suffer from ‘future shock’ or retreat into the narrow safety of the community of their origins. Rather, they will be able to take control as an agent of social design in the spaces in which they live and work. The guiding metaphor for their social life is the networked ‘we’: humanly interconnected, discerning, agile and flexible.

See Paulo Freire on Education that Liberates.

The results of this New Learning will not be student scores spread neatly across a bell curve, a few learners at the bottom of the class, most clustered around the middle and a few at the top. There is no room for failure and marginalisation in the school of the New Learning. Poor results are anathema for individuals and society. Nor is there room for a bulge of mediocrity.

Children will grow up to do different things in their lives, and as adults may make comparable, though varied contributions to their worlds. That should be the basic assumption of education, and reward and credentialling systems need to make this abundantly clear. When learners leave school they should not be branded with a spread of exit scores statistically derived from narrow or anachronistic norms of success and failure.

At the failure end of the spectrum, the stakes are higher than ever – even affluent societies cannot afford a dysfunctional underclass. At the success end of the spectrum, maybe the ‘smart’ ones are just smart at playing the game of school. Are we simply rewarding those who play the system rather than those who are creative and innovative? Is this the kind of person we really want as the worker and citizen of the future? Instead of these bald numerical scores, perhaps students should leave the various stages in their learning with complex and rounded stories of what they have actually done in their lives and their learning, stories that can be read in their fullness by other educational institutions, employers and the community.

In this chapter, we have told a story of tradition and change, from the didactic education to authentic education, to our proposal for the transformative world of New Learning that is only now emerging and the shape of which is not yet clear.

We have painted this picture of change in the broadest of brushstrokes. History, however, is rarely a succession of neatly defined periods. Today, you will find educational settings anywhere in the world that predominantly reflect one of these three approaches or paradigms for learning. And within one of these sites you may find moments and incidents that reflect one approach in one moment, and another approach in another moment. You will find patterns of variation from country to country, school system to school system, school to school, classroom to classroom, teacher to teacher, discipline area to discipline area and even from one moment to the next within the life of a single classroom. Sometimes one approach – didactic, authentic or transformative – will seem appropriate for the time and the setting. Other times it will not.

In this book, we try to imagine what a new phase in the development of modern education will be like. We will be to looking for signs of things to come in the innovative educational practices of today. This, we believe, is not simply an act of imagination, a willful utopianism. Given the changes occurring today – globalisation, community diversity, new technologies, changing work, and the formation of new kinds of persons with different sensibilities, to name just a few gusts among the winds of change – the New Learning of which we are speaking may soon become a necessity.

Unless, that is, we allow schools to slip into a crisis of irrelevance. We’ll know when such a crisis arrives, because it will translate into employers’ complaints about graduates, into student discipline problems, and into a general community anxiety that schools are not teaching learners what they need for the contemporary world. On these indicators, in many places, this crisis has already arrived.