Productive diversity: Towards New Learning

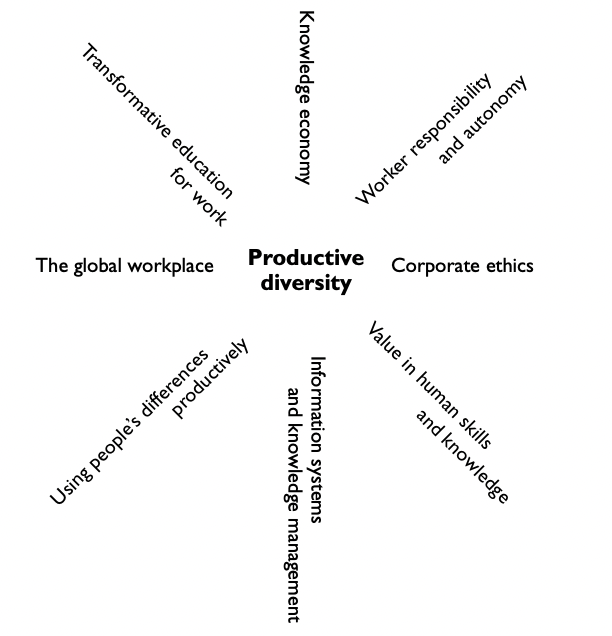

‘Productive diversity’ is a term we use to describe what every now and then comes after post-Fordism, particularly in those moments when the laws and limitations of post-Fordism are addressed and or partly overcome. It is a term that emerges from our work and others’ about the changing nature of work. Productive diversity works on finding practical solutions to what doesn’t work in post-Fordism. Each moment of the new demonstrates what could come next and what, it seems at times, should come next.

See Productive Diversity Case Studies.

Productive diversity stands for a number of things: workplaces that foster autonomy and responsibility, that devolve power, that honour the differences among their members – that, in short, establish new working relationships and a new balance of agency (Page 2007). Productive diversity straddles the actual and the possible, the emergent and the ideal. It builds on the foundations of realism about today but with a strategically optimistic view of what may be possible tomorrow. What we have called ‘New Learning’ is the kind of education that will best serve a world of work characterised by productive diversity.

Dimension 1: Technology

The flexible specialisation that comes with post-Fordism changes the way in which the modern factory operates. The technologies of productive diversity centrally depend on information and communications systems, not only in the new knowledge industries but to transform manufacturing and primary industries, too.

See Daniel Bell on the Post-industrial Society.

Whereas the first stage of the computer revolution advanced the level of automation possible in the traditional workplace, the second wave changes the workplace itself. To take just one aspect of change: the architect, the banker, the designer, the teacher no longer have to go to fixed geographical locations to do their work. They can do it online, for periods of time at least. They can work in virtual teams whose members do not even have to be in the same country. Perhaps they are members of huge organisations; perhaps they are sole traders or micro-businesses. Either way, the boundaries between work and home, personal and organisational, local and global, become blurred.

The teacher in a Melbourne home may be tutoring a child in China in English. The architect in London may be working with a design and construction team in Jakarta. The banker in Beijing may be organising transactions between manufacturers in China and stores in Europe. Differences are closer to home than ever – literally as well as metaphorically. The industrial systems of Fordism and post-Fordism created neighbourhood diversity, insofar as they attracted migrant labourers from many cultures to manufacturing towns and cities. The information systems of productive diversity remove all physical barriers to direct engagement with diversity, from the intimacy of the home office to the ends of the Earth.

The new technologies, moreover, bring with them new economies of distribution. There is no cost advantage in proximity. If you can afford the computer and the Internet connection, messaging, file downloads and Internet telephony are virtually free. New media forms abound – blogs and wikis and social media sites that blur the boundaries of writers and readers, creators and consumers of culture. We are all users now. These are disruptive technologies, unsettling centralised models of commerce and displacing them with highly devolved production of information, culture and services.

The changes are deep. Economists have even had to rethink the nature of value. In the industrial era, value was in physical capital, and technologies were embodied in machines. The factory was more or less worth the value of the land on which it stood and the cost of building the plant. In the ‘knowledge economy’, the capital value of an enterprise is increasingly located in what economists call ‘intangibles’: brand; product or service design; reputation; business systems; customer relationships and loyalty; intellectual property; human skills; and the capacity of the organisation to capture, systematise, preserve and apply knowledge. These intangibles are more important to the viability of an enterprise today than physical capital (Stewart 1998).

See Yoneji Masuda on the Information Society.

The fundamentals of value today are in human skills, relationships, culture, knowledge and learning. Complex and changing technological and human expectations require flexibility, creativity, innovation and initiative.

The reasons why the primary source of value has shifted from physical to human and cultural capital can be traced, in part, to the nature of the new technologies. These technologies are more infused with human meaning than ever before, their human interfaces drenched with textuality, visual symbolism and representational and cultural force. The irony here may not be that today’s large changes in human society are technologically determined. Quite the reverse: it may well be the case that we are finding new ways to humanise the machine.

Dimension 2: Management

Fordism is a system of top-down hierarchical control. Post-Fordism is a system of soft power. You might get sent off to a training course designed to build teams, improve your communication skills or enhance shared values. Such courses may have outdoor or physical activities, possibly involving an element of adventure and risk. In this artificial environment, all the differences seem to fall away. Your organisation may also develop vision and mission statements. It is, of course, always striving to be the best company, producing the best products or providing the best services. You are expected to believe it, and even better, to have come to that conclusion by yourself. You ‘clone’ to the organisation’s culture. You personify the organisation by sharing the ‘passion’ for all it does. You project the aura of good feeling that surrounds the organisation by saying ‘have a nice day’ to the customers.

The effect of this approach is cultural homogenisation in the workplace. The organisation seems to be saying to newcomers something like this: ‘We will welcome you into the corporate fold providing you take on our shared values and cultural style, to take on the corporate persona. We want you to it in. If your differences are noticeable, then we will deal with them by not making an issue of them. For your part, just leave them at the corporate door each time you enter.’

The major problem with this approach is that cloning or cultural assimilation is never so simple. Rarely can people hide their differences effectively. It is also often counter-productive from an organisational point of view. The organisation wantonly neglects potentially invaluable competencies, experiences and networks. ‘Glass ceilings’ develop that restrict that contribution of genuine talent just because people don’t it the existing corporate style, or when they are excluded by ‘old boy’ or insider networks. The organisation says it values everybody, but if you’re a woman, or a member of an ethnic minority, or different in some other way, it may just happen that you don’t get the recognition and the promotions achieved by those who conform more closely to its dominant cultural image.

This becomes a system of soft power. The problem is that, despite its egalitarian words, post-Fordism often turns out to be just another system of exclusion. As soon as it is put in place, it runs into serious trouble on a number of fronts. In a world of increasingly diverse local communities, the organisation does not necessarily attract the best recruits. Instead, it limits itself to a narrow demographic that reflects its equally narrow cultural self-image. Within the organisation, the mediocre seem to float to the top just because they are well connected and happen ‘to it’. Meanwhile, other people who know their jobs extremely well, perhaps better than the team leaders and managers, are excluded. In an era of globalisation and locally differentiated niche markets, this makes little sense. An organisation that is good at dealing with its own diversity will be better able to deal with a world of diversity. Its members will not expect the next employee, or next customer, or next supplier to have the same culture.

The post-Fordist organisation also breeds a culture of uncritical conformity. People are isolated as critics or trouble-makers when they might have a valid point of view that the organisation should address. The critical non-conformists may be the people to whom a genuine ‘knowledge organisation’ should be listening most attentively. Besides, does anybody really believe the overblown rhetoric of vision and passion and shared values? Post-Fordism often creates a suppressed underground culture of people who know the critical truth. They grumble privately to each other, but never get the chance to contribute what they know.

Productive diversity is a response to the inherent deficiencies of post-Fordist work organisation. Instead of attempting to force cultural homogeneity upon members whose lifeworld origins are diverse, the productive diversity organisation attempts to capitalise on the talents of diversity. Valuing diversity is an important part of team building, not just to ensure the contribution of all involved, but also to draw on the resources of diversity: different points of view, styles of communication, ways of working and life experiences. These may be based on gender, ethnicity, cultural aspirations, life experiences, interests, specialist knowledge or any number of other differences.

The productive diversity approach to organisational culture promotes habits of mind through which people are constantly prepared for the unpredictability of engagement with others whose lifeworld experiences are varied. It recognises the value of these differences and negotiates them effectively. This represents a fundamental shift in the culture metaphor, from one that is founded on a notion of cultural commonality to one where negotiating diversity is key. Diversity supports a range of practical purposes, from the customisation of products and services for niche markets, to working the dynamics of teams drawn from a globalised labour force, to building networks with other organisations whose occupational cultures are very different.

The organisation that embraces the tenets of productive diversity replaces the soft power of post-Fordism with a more honest and genuine devolution of power. Power is vested in the hands of the organisation as a whole: the people who belong to it and the clients who relate to it – in all their diversity. This is a system of stakeholder control. Management is through participation, negotiation and collaboration. It is also an approach that values dissent. In fact, people in this kind of organisation even turn dissonance into a productive force. This includes dealing with bigger-picture ethical issues of inequality, sustainability and customer interests before they become a serious threat to the very existence of the organisation.

The society of rigid, hierarchical Fordist organisations engendered relationships of command and compliance in all social agencies, not just in the workplace (the bosses and supervisors whose orders were to be obeyed), but also in homes (the heads of households who made decisions and disciplined) and in schools (the headmasters and teachers, mandated curricular content and tests of definitively correct answers). For every command personality, there had to be a multitude of unquestioning functionaries, and the system depended upon their compliance. The ideal worker was compliant; the ideal learner in the classroom of disciplined knowledge was compliant. Today, the command personality is an anachronism. The devolution of social and cultural responsibility to the furthest reaches of the organisation is a prerequisite to high performance.

See Peter Drucker on the New Knowledge Manager.

Dimension 3: Workers’ education and skills

The working world of productive diversity raises the knowledge and skills expectations of its members still further than that of the post-Fordist organisation. Technologies change at a quickening pace, which means that workers need to update their content knowledge and skills continuously. What you learned at school, college or university soon becomes out of date, which means that you need to take another degree, or a refresher course, or a training program, or to teach yourself through an e-learning program, or to learn the latest version of a software package from the help menu and with ‘over-the-shoulder teaching’ by co-workers (Twidale 2009). Because both expertise and technical knowledge has a shelf life that is becoming shorter and shorter, learning and skills development have to be lifelong and life-wide.

See Gee on the Needs of New Workplaces.

The skills of productive diversity are also deeply interpersonal: how to collaborate with colleagues whose life experiences and skill sets are different and complementary to your own; how to share knowledge as a teacher as well as a learner; and how to relate to clients and provide them with products and services that address their varied needs and interests.

Meanwhile, the very nature of ‘career’ changes. Gone is the stable pathway, based on seniority or even a simple idea that merit means conforming to a uniform standard. Jobs don’t last so long. People regularly swap employers, and even industries. Careers head off on unanticipated tangents, and one’s credentials come to be made up of accumulations of divergent experiences that previously might have been regarded as bizarre. What a worker takes with them from one job to the next is a ‘portfolio’ of experiences, and the more varied and broadly focused this portfolio, the more rounded and valuable they will appear to a new employer.

The changes in the nature of work that we have described in this chapter have enormous implications for education. The main game is now knowledge and relationships – the stuff of human rather than fixed capital. They are things that are made by learning. For this reason, learning has become pivotal to the whole economy (Peters, Marginson, and Murphy 2008).

See Educating for the Knowledge Society.

The economy of the changing present and near future requires people who can work flexibly with shifting technologies; who can work effectively in the new relation- ship-focused market and community environment; and who are able to work within an open organisational culture and across diverse cultural settings. We have characterised the kind of education suited to the new nature of work as ‘New Learning’, or transformative education. Preparing tomorrow’s knowledge worker is one of the principal tasks for contemporary educators. The success of teachers and educational communities as they undertake this task will be reflected in the performance of economies and the welfare of nations.

See Davidson on New Learning for New Work.

Dimension 4: Markets and society

‘Any colour you like, so long as it’s black,’ said that heroic command personality, Henry Ford. Today, there can be no such entrepreneurial heroism because the customer is ‘always right’ and products and services need to be customised to mesh with the multiple identities of niche markets. These markets are differentiated according to age, gender, ethnicity, sexual preference, style, fashion and taste. So, we have the big SUVs, the smart sports cars, the spacious family cars, the micro cars for crowded cities, hybrid cars for the environmentally conscious, cars of any hue and trim – so many permutations, in fact, that an order sometimes has to be placed before a vehicle is even manufactured.

In the era of post-Fordism, product differentiation was often no deeper than the coat of paint and a few accessories. In the era of productive diversity, consumers are drawn to representations as much as they are to physical entities. Here, the play of the product is about the consumer’s identity and not just practical utility. The product is now a complex thing comprising design, aesthetics, image, concept, brand association, service values – and utility – but not utility first and foremost. The use-value of the transaction is cultural as much as it is utilitarian. This is also why organisations increasingly find that they need to trade on the intangibles of image, ethics and the making of moral meaning.

In an optimistic view, the transition to post-Fordism and then productive diversity may well indicate that we are on a social course where expanding expectations take us beyond the gross inequalities of past and current economic systems. The promise of equity may lead people to demand real change, particularly if it creates an expectation that proves disappointing. With a gentle nudge, small improvements within systems logic may turn into utopian aspiration for something more. In education, this might mean more than simply preparing students to get good jobs in the new world of work. It might also mean building a social imagination grounded in an ethics of equity that extends beyond the logic of the modern system of paid work with all its inequalities. How, for instance, might a deepening understanding of globalism, difference and the system of working for money open out larger questions of our human natures and the ways we inhabit the Earth?

The purpose of education is not just to serve the needs of the economy by creating useful workers. The economic rationale behind much of today’s talk of educational change is, on its own, too narrow. Participating in the formation of useful workers is only one of several of the fundamental purposes of education.

In the following two chapters we discuss the role of education in creating fully participating citizens and shaping persons who are at home in their different identities. In order to be useful and successful in today’s work, individuals need to be able to participate, to be good ‘corporate citizens’. They also need to be a certain kind of person, comfortable with their identity and able to give something of themselves in their work.

If the educational basics of the traditional classroom produced well-disciplined but compliant persons who relied on the stability of the facts and theories they had been taught, the New Learning must open up a space where individuals can develop the skills and capacities of adaptability, flexibility, initiative and innovation required by the new workplace.

See It’s Our Responsibility to Engage Them.

As we respond to the radical changes in working life that are currently underway, we need to tread a careful path that provides students an opportunity to develop the knowledge, capacities and sensibilities that will allow them access to new forms of work. At the same time, our role as educators is not simply to be technocrats. It is not our job to produce docile, compliant workers who fit into whatever regime of work happens to be in place or emerging at a particular moment in time. Learners also need to develop the capacity to speak up, to negotiate and to actively create for themselves the conditions of their working lives.

Indeed, the twin goals of access to work and critical engagement need not be incompatible. The question is: how might we ground our educational work in the pragmatic needs of today’s high-tech, globalised and culturally diverse workplaces, yet at the same time relate these to educational programs that are based on a broad vision of the good life, creativity, innovation and an equitable society?

The contemporary workplace invests in the creation of new systems for getting people motivated and making them productive. In some moments, these are exploitative and oppressive. In other moments, we might optimistically conjecture that such systems might be the basis for a kind of democratic pluralism in the workplace and beyond. In the realm of work, we have called this optimistic vision productive diversity – or the idea that the multiplicity of cultures, experiences, ways of making meaning and ways of thinking can be harnessed as an asset. Paradoxically, perhaps, democratic pluralism is possible in workplaces for the toughest of business reasons. Economic efficiency may be an ally of social justice, even though we know from experience that it is not always a staunch or reliable one.

In building the idea of a New Learning whose goals are transformative, we have attempted to develop an agenda for education that will work pragmatically for the ‘new economy’, and for the most ordinarily conservative of reasons. It will help students to solve problems and get a decent job, and that’s particularly important when the dice of opportunity seem to have been loaded against particular individuals and social groups.

In another reading of today’s economy, however, we should be under no illusions about the liberatory potential of the new economy or even, at times, about how ‘new’ it actually is. The discourses and practices of today’s workplace can just as easily be interpreted to be a highly sophisticated form of co-option. A lot of people are left out of the new economy: the service workers in hospitality and catering who wash dishes and make beds; the illegal immigrants who pick fruit and clean people’s houses; and the people who work in old-style factories in China or call centres in India. Patterns of exclusion remain endemic.

From this perspective, we need to take our educational agenda one step further, to help create conditions of critical understanding of work and power. This will create a kind of knowing from which more genuinely egalitarian and productive working conditions might emerge.