Inclusion: Towards New Learning

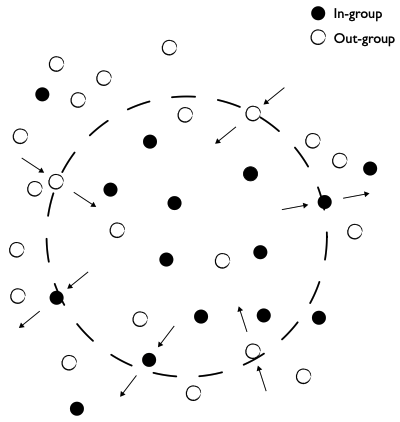

Our case for an inclusive approach does more than simply recognise or acknowledge differences. It is grounded in an understanding of the fundamental social dynamics of diversity. Differences never remain still. They are not states that are simply to be found, classified and dealt with. They are always moving. Differences, moreover, are invariably relational. Groups cannot be neatly categorised and described as though that were the end of the story. Rather, they are constituted through relationships in which one group is defined in relation to another. Groups exist in dynamic, and never stable, tension – class to class, gender to gender, culture to culture. They are also internally differentiated. In fact, a rough general metric would be that the spread of internal differences within any demographically defined group is greater than the average difference between groups. This means that the demographic groupings, while helpful to our understanding of the historical and experiential basis for certain moral agendas and social claims, are oversimplified and sometimes counter-productively so. Finally, the differences intersect. There are not just a dozen or so key categories of difference. For any individual the chance of any one particular combination (class, gender, race, sexuality, body form, affinity and the like) is so low that in their mixed-up peculiarity, they can only ever belong to the tiniest of minorities. This means that throwing a person into one of the larger demographic categories may do disservice to their more precisely defined needs and interests (Kalantzis and Cope 2009).

See Kalantzis and Cope on the Complexities of Diversity.

Moving from ‘recognition’ to ‘inclusion’ means to shift emphasis from static ‘diversity’ to dynamic ‘divergence’. Differences never stand still. We can’t assume they should stay the same. In fact, no longer can we remain content to leave differences more or less the way they are. Sometimes, we may want to move them along. This can be either from the perspective of an insider – a woman who wants to change the role of women, or an indigenous activist struggling to improve the conditions of life of their people, for instance. Or it can be from an outsider’s perspective, in cases where educators assist learners in their self-transformation or growth, helping them to achieve dreams and aspirations that may have seemed beyond the scope of possibility within the narrower confines of their lifeworlds.

See Kalantzis and Cope on the Conditions of Learning.

Authentic education reflects diversity in the world as it is found. Our case for an inclusive, transformative view of education, by contrast, works on agendas for action. It works with learners to invent and reinvent themselves and their worlds – as high-performing workers, participating citizens and confident personae. Such an approach may be driven by a range of social and self-transformative agendas, from establishing and building a career, to entrepreneurial innovation, to ethical concern for social justice, to a practical concern for the future of the environment. Our New Learning proposal supports a full spectrum of potential individual and social objectives, from the pragmatics of self-advancement to the social-ethical agendas of emancipation and environmental sustainability.

See Inclusive Education Case Studies.

Dimension 1: Material conditions

Social class

With the exception of several small, remnant, communist states, the world that entered the 21st century used mostly market-based methods for material resource distribution. Workers work for business owners. They are paid less than the full value of their labour. Owners with the good fortune to have been born to ownership or the good luck to have acquired it, make a profit and become wealthy. In the 19th century, Karl Marx thought the workers in this kind of market–capitalist system would get poorer while the owners got richer, and that this disparity would eventually bring the system down. And, from Russia to Vietnam, the capitalist system did come down for one-third of the world’s population in the first three-quarters of the 20th century.

Marx did not envisage, however, that many of the workers in capitalist societies would gradually become better off, at least to the extent that they would be satisfied enough with their jobs, what they earned and what they could afford to buy. Indeed, although greatly reducing disparities in wealth, communism failed to provide the mass of the population with the consumer goods and freedom that capitalism offered. Since the end of the threat of communism, the gap between the less and the more affluent has grown all around the world, and continues to grow in ways that are still explicable in terms of the underlying logic of the capitalist system.

Since the collapse of classical communism and the end of the Cold War, there has been little incentive to change the capitalist system in any fundamental ways. Nor has there been a realistic possibility of achieving fundamental change. Other major changes can be and have been more readily made; for instance, to establish gender relations on a more equal footing, or to eliminate the worst excesses of explicit ideo- logical and institutional racism.

Though material inequality seems an intractable problem for the moment at least, some if its worst excesses remain ethically intolerable and practically unsustainable. Even the most enthusiastic supporters of the capitalist system would agree that there are great dangers when poverty is experienced as perpetual hopelessness. Such poverty is a breeding ground for violence, criminality, war and terrorism.

Education seems helpless to address the deep structural sources of material inequality, even though educators must deal with its consequences on a daily basis. Despite the neoliberal retreat from the large-scale project of reducing inequality, states around the world continue to assume some responsibility for redistributive justice. They do this domestically through the taxation and welfare systems and inter- nationally through aid programs.

Some things, however, education can do. Education is a key variable in the nexus between work and material resources. The most obvious connection is that education creates personal knowledge and intellectual capacities that provide entry into forms of work that pay more. The education–work–material resources connection is one of the great ‘opportunity’ or mobility promises of an unashamedly unequal society. If you don’t inherit material resources or chance upon them, education is almost the only path to mobility. Without education, the promise of opportunity at the heart of democratic capitalist societies would ring extremely hollow. If education can’t do redistributive justice by reallocating material resources, it can do it by providing symbolic or knowledge resources to individuals and groups.

As it happens, knowledge resources are becoming more pivotal to the new capitalism, and this opens new potentials and creates new responsibilities for educators. Politicians and captains of industry tell us that knowledge is now a key factor of production, a fundamental basis of competitiveness – at the personal, enterprise and national levels. And as knowledge is a product of learning, education is more important than ever. This is why education has become such a prominent topic in the public discourse of social promise. The expectations of education have been ratcheted up. More than ever before, our political leaders are saying that education is pivotal to social and economic progress. This does not necessarily translate immediately into greater public investment in education (a businesslike approach, one would think). But today’s rhetoric about the importance of education does give educators greater leverage in the public discourse than we had until recently. Stated simply, in a knowledge economy in which more and more jobs require greater depths of knowledge, schools must do what they can to bridge the knowledge gaps. If they can do this, they are at least doing something to ameliorate the worst systemic material inequalities. Schools, in other words, have a new opportunity, a new responsibility and a new challenge to build societies that are more inclusive of social classes whose access to material resources was historically limited.

Locale

The dynamics of locale are changing, too, as cities spread into their hinterlands and as regions themselves turn into semi-urbanised sprawl. These create more complex human geographies, where wider differences of wealth, culture and affinity find themselves more closely juxtaposed.

Paradoxically, the magnetic attraction of the city is no longer so powerful as it once was. The Internet, satellite TV and next-day delivery can connect almost any place in the world to any other. As the world’s big cities become more expensive, businesses are moving to less-expensive regional places. The poor are moving to get jobs and live in places where they can enjoy a better standard of living, even though their wages may be low. Welfare recipients are moving to regional areas too, so their meagre payments can be stretched further. Meanwhile, people of the middle class are moving to places where they can purchase a better lifestyle for what they earn – a bigger house for the same money, and cheaper products and services. The rich are establishing at least part-time, but also sometimes full-time, places of retreat, commuting and telecommuting to their places of work or business. All these fractions and fragments of social class find themselves uneasily juxtaposed in newly growing regional cities, towns and semi-rural ‘sprawl’ (Bruegmann 2005).

If suburbia was the characteristically new urban form of the 20th century, the growth centres of the near future and the sites of our next wave of social transformation are in a distributed ‘extra-urbia’. This new extra-urbia consists of the semi-rural hinterlands of big cities, small regional or remote urban communities and rural or remote households that nevertheless can now subsist in a pseudo-urban or virtually urban domestic economy. No matter where they are, extra-urban households have a relation to information, culture, work and commodities equal to any urban household and at a fraction of the cost – as a consequence of cheap freight and online shopping, e-learning at every level of education and telecommuting, and the fact that any book or piece of music or film in the world is now within reach of an Internet download, or satellite TV or next-day delivery. The new economy is producing completely new geographies from the urbanisation that characterised an earlier modernity.

For these reasons, education outside the big cities becomes an increasing matter for concern. The composition of extra-urban communities is changing rapidly, representing extremes of poverty and wealth, and diversity of identities as great as any. Equitable access to the full range of quality education becomes a challenge for designers of e-learning environments.

Meanwhile, the local becomes global – the rapid communication connections that bring people so close, the products that can come here or go there by overnight dis- patch, the streets in which one household connects into one global diaspora and the next household another. Global movements of people are picking up the pace, particularly as more of the productive population retires, and as the population in the reproductive age range has fewer children. The consequences are sometimes orderly but often disorderly global movements of people.

Family

Family types are more varied, and the variations are regarded as less aberrant, as a smaller proportion of households reflect the older norm of the nuclear family. Fewer people get married, or when they do, it is later than previous generations. Fewer families are founded on lifelong monogamy. Polygamy is more visible and acceptable, in all its varied forms, from fundamentalist religious communities to the de facto polygamy of ‘extramarital’ relationships. Reproductive alternatives have also expanded, raising for many children the question of the identity of a biological parent. In the case of same-sex couples, children may or may not be biologically related to one of their parents, and this creates yet another dynamic of family and identity.

Families are also affected by broader social transformations. The neat separation between the domestic and public economies becomes blurred, not just in terms of the gender locations of men and women, many of whom now have to perform competently in both sites, but also in terms of the old institutional separations. ‘Family friendly’ working conditions are created to encourage the lifestyle choices of ‘new men’ and ‘new women’. The possibility of working at home or telecommuting arises with the help of the new technologies, a consequence of which may be that family and work do not have to be physically separated.

Specific family circumstances also create increasing concerns for social institutions, such as schools. Emotional relations between parents and children, neglect, violence, sexual abuse, substance abuse – these are all factors that can have a pro- found effect on children’s wellbeing and their propensities to learn.

The child’s ‘cultural capital’, the advantages or disadvantages they bring to the school setting from their families, also plays an increasingly recognised role. Some kinds of families provide children with forms of cultural capital that advantage them – ways of speaking, thinking and seeing the world. Others do not seem to have the cultural capital they need to do well at school. The key to success and failure at school is the degree of distance between a child’s lifeworld experience and the culture of schooling.

Given the range of family forms and circumstances today, coupled with the growing significance of education as a path to social enablement, patterns of educational inequality present themselves as unconscionable. They limit learners’ opportunities and prove counter-productive to the needs of contemporary society. To be more inclusive, schools develop strategies that engage with the identity of every student, no matter what their lifeworld or family circumstances. The gap between the child’s lifeworld experience and the culture of the school should not disadvantage them. The school cannot change the child’s lifeworld experience. It can, however, build an inclusive culture and curriculum that at least reduces lifeworld distance as a variable affecting learner outcomes.

See Herbert on Aboriginal Pedagogy.

Dimension 2: Corporeal attributes

Age

Today, the traditional separations of chronological age seem to be breaking down. Or, at least, they seem in need of a social transformation that will actively break them down.

How early should formal education begin? And who should do it – professional institutions of early childhood education, or parents with the assistance of educational toys, video and television? Age-related measures of learners’ capacities also seem less relevant, as the range at any one numerical age – of emotional maturity, conceptual capacity or forms of responsibility – seems greater today. Finer grading into more homogeneous groups does not seem to be the answer. Rather, an inclusive approach may involve having a wider range of ages in a group, and teaching strategies targeted to the dynamics of difference, including reciprocal learning, peer mentoring, collaborative activities, and learners pursuing varied interests and tasks. This represents a challenge to the conventional communication architecture of the classroom and its everyone-on-the-same-page approach. A reinvention of pedagogy may be necessary to meet the demands of the pluralistic divergence in today’s classrooms.

As young people mature earlier and stay dependent longer, new frameworks of responsibility may be required. Their learning may increasingly be connected with or supplemented by responsibilities in the community, on a voluntary basis or involving a nominal payment. The neat institutional separation between school and work may no longer be sensible or viable, particularly as the proportion of the population within the age range of the traditional labour force declines. Nor will education be so straightforwardly attached to a particular time of life. It will necessarily be lifelong and life-wide. People may also be able to, and want to, work longer, be that in paid or voluntary work, and to do this they will need to constantly update their skills. Once retired, people will need to learn new things if they are to maintain their capacity to participate in a rapidly changing world.

The overall effect is to blur the traditional boundaries of age and of age-related learning institutions. This creates new opportunities and challenges for education. An inclusive education will allow you to learn a wider range of things in a wider range of ways at a wider range of sites, at any and every age.

Race

It has lately become possible to return to the question of race, aided conceptually by the findings of recent genetic research. For a long time, the biology of race had been discredited because it was linked to an older science of physical anthropology, which measured differences in skull capacity and drew spurious conclusions. Later it was connected to arguments about race and intelligence, also now discredited (Shenk 2010). New research examines human genetic divergence from DNA samples. This research has demonstrated that human beings are all very closely related genetically. There is also such a degree of genetic mixing that it is almost impossible to delineate one group from another in biological terms. The geographical departure from the original source of humans in Africa is so recent in generational terms – perhaps 500 generations for the peoples of the Americas and 1000 for the peoples of Europe – that the differences are insignificant (Cavalli-Sforza 2000).

The result is that race is no longer justified as a meaningful category for differentiating the intelligence or educability of human groups. It is now widely recognised that there is no scientific basis upon which to argue that different educational outcomes for racially defined groups at school are based in the inherited, biological differences in the brain. Changes in attitude to racial difference have led to a widespread recognition that such differences are, and have always been, the product of political, economic and social conditions.

Racism, however, remains an important category, even if its forms have become more subtle and harder to address. Institutional racism is an affront to international human rights covenants and is illegal in most places. The discourse of explicit racism is unacceptable in public contexts. But the legacies of racism persist: in the patterns of inequality that reproduce themselves; in the ‘invisibility’ of some groups in the public culture; and in the ‘choice’ of groups to live in separate and unequal communities based on locality, employment and affinity. Racism is so entrenched and pervasive that outcomes do not necessarily improve even when desegregation is enforced, such as when children are ‘bussed’ from the area in which they live to a desegregated school in another area. The challenge of social and educational inclusion today is to address these harder-to-identify and harder-to-remedy forms of racism. The neoliberalism of recent times and the backlash against political correctness, however, have made the discourses and social policies around race more complex than in earlier periods of overt racism.

See Brown v. Board of Education US Supreme Court Judgment

See Martin Luther King, ‘I Have a Dream’.

Sex and sexuality

Sex is no longer regarded as a definitive natural inheritance. People have a greater capacity than ever in the past to remake their bodies. This could be in order to con- form more closely to an idealised sexual aspiration, such as breast or penis enlargement. Alternatively, people can choose to sculpt their bodies surgically and with medication in order to change sex from the one assigned to them at birth. People who make this choice are called transsexual. Transmen are people who have been born female and who have changed to be men; transwomen are people who have been born male and who have changed to be women. Transsexual people may have a range of sexual orientations (Hausman 1995). An intersex person is born with genitalia and other sex characteristics that are ambiguous. They may choose to remain intersex, or move in the direction of one or other sex. In the past, this decision was often made at birth by doctors or parents. Medical procedures were performed that sometimes took people in a direction that they would not have chosen for themselves (Preves 2003). Today, sex and sexuality are a matter of personal decision and a commitment to be true to what the person considers to be their natural self (Herdt 1994).

Sexual orientation is considered by many today to be an aspect of a person’s nature, or corporeal inheritance (d’Augelli and Patterson 2001). This is manifested psychologically (a person’s erotic desires) and in practice (the sex partner or partners one chooses). The principal categories of sexual orientation are homosexual (gay and lesbian), heterosexual and bisexual. Other forms of sexual orientation include celibacy or a deliberate choice to refrain from sex irrespective of desire; asexuality when people are not sexually attracted to others; and auto-sexuality or a preference for auto-arousal. People may opt for one of these forms of sexuality, or a combination; for instance, the celibate lesbian, or the transwoman whose sexuality is exclusively autoerotic, or the person who is a heterosexual male who also cross-dresses and gains autoerotic pleasure from this. The range of sex and sexualities today encompasses a widely variable range of body forms, sexual identities and sexual practices.

What do schools do? Identities grounded in sex and sexuality are profoundly the concern of an institution whose purpose is the development of children and young people into adults. Vexing questions arise, such as the age at which sexual orientation can be recognised and sex reassignment considered. There is the question, too, of the role of the school in negotiating these complexities, in so many areas, from counselling to curriculum. The situation is further complicated by divisions in the community, particularly when some people condemn the range of sex and sexual orientation options available today while others support what they consider to be a fundamental personal liberty. The consequences of practices that are prejudicial or exclusionary are dire, even when pressures are subtle, as evidenced in the levels of depression and rates of suicide among young people struggling with their sex and sexuality (Rasmussen, Rofes, and Talburt 2004).

Physical and mental abilities

Stereotypical views of the normal body are disrupted by the growing acceptance of a wider range of body forms. Normality, ironically, is destabilised by images of unrealistic hypernormality – from the tall, dangerously thin female models to the overdeveloped body builders. Ideas of the normal body are also thrown into question by a wider range of interventions on the body: dieting and anorexia; body building practices and drugs; and tattoos, body piercing and hair designs.

The range of recognised disabilities also expands. The classifications become more finely grained as we become better informed by the research of educators, social workers and medical scientists. Disabilities relevant to student learning today include:

- arrange of hearing impairments from various forms of restricted hearing to deafness (Roeser and Downs 2004)

- sight restrictions of different kinds, such as myopia and colour blindness through to full blindness (Barraga 1983)

- speech impairments of many varieties and with differing impacts on speech (Bishop and Leonard 2000)

- orthopaedic conditions that limit motor functions, including cerebral palsy, spina bifida, muscular dystrophy, clubfoot, amputation, paralysis, stroke and arthritis

- developmental disorders, such as Down Syndrome and small stature (McGuinness 1985)

- mental disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, phobias of various kinds, anxiety disorder, neurosis and obsessive-compulsive disorder; and emotional, social and behavioural difficulties, such as autism, Asperger’s Syndrome, attention deficit disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Halasz et al. 2002)

- learning disabilities, including visual discrimination, auditory discrimination, spatial or temporal perception, dysphasia (language ability), aphasia (language loss), dyslexia (reading difficulties) and dyspraxia (difficulties in coordination and movement)

- chronic illness.

These and other disabilities may be inherited, or acquired by accident or with age. In the past, these disabilities were identified exclusively through a clinical lens. Today, disability is regarded as a social construction as well as a clinically identifiable condition of the body or brain. The social construction may take the form of the stairs that prevent wheelchair access, or the websites that do not meet accessibility standards for the visually impaired, or other people’s generalised expectations of ‘normality’. It may be the image and self-image of disabled people that limits their access to some social domains. Disability activists throw into question the ability ‘norm’. They also insist on the right to assistive technologies and to education and training that does not focus on the lack, but positively nurtures parallel and compensatory abilities. Disabled people can do many of the things able-bodied people can do, albeit in different ways. And the distinction between able-bodied and disabled is never so clear. Perhaps the able-bodied are only ever temporarily so. They are always vulnerable to the possibility of accident or disease, and the aged usually face one form of disability or another.

The question for institutions, such as schools, is how does one create a genuinely inclusive environment for people whose body forms and mental capabilities are so manifestly various? As the range of disabilities comes to be more adequately recognised and as the variety of meaningful educational responses becomes better known, disability presents itself as a bigger and more pressing issue for educators. Taking into account the enormous range of permutations of abilities and disabilities, and the overlay of other material, corporeal and symbolic dimensions of difference, there can be no simple classification of challenges and solutions.

See Bowe on Barriers to Disabled People.

In the past, differences of body form were ignored, or the people most deviant from the norm were sent to special institutions. Today, ‘mainstreaming’ and integration are often attempted. A danger here, however, is that communities of similar experience are broken up (for instance, sign-language communities). Teachers end up dealing with so many differences, each requiring such specific educational responses, that they sometimes find themselves dealing with specific situations outside the scope of their competence. The solution, in part, is to work collaboratively with experts outside the classroom, and also to create an open learning environment in which the experience of learning can vary according to each learner’s needs and interests – from each according to their ability, and to each according to their need.

See Universal Design for Learning.

Dimension 3: Symbolic differences

Culture

A paradoxical thing happens to culture in the era of total globalisation. The whole world is opened as a potential domain for representation and action – products, media, communications, travel. In one moment this appears to be a process of homogenisation – the consumer products that look much the same wherever they are, the media and entertainment giants that make their presence felt everywhere, and English as the lingua franca of the new, digital media. In another moment, these very processes of universalisation prompt people to go out of their way to make poignant differentiations. We can purchase the products whose special quality is that they were made in a distinctive place. The media tell stories of awesome or shocking differences in culture and circumstance at the ends of the Earth. Many small as well as large languages and cultures flourish because the new media are so accessible. Then there is the growth in travel and tourism, which would not be worthwhile if the destination was not different. The cultural logic of globalisation, in other words, is as much one of cultural divergence as cultural homogenisation. For every cultural thing that seems to be becoming pragmatically – or distressingly – standardised, there is something else that people are actively trying to differentiate.

In the case of ethnic and indigenous cultures, today’s paradoxical forces of globalisation provide new openings for cultural self-differentiation, local community self-governance and more powerfully interconnected diasporic communities. And another paradox: you might be concerned that your neighbour’s lifeworld is on a worryingly diverging tangent to your own (and where do their loyalties really lie?). However, people who feel they genuinely belong, in their difference, develop a more powerful and effective sense of inclusion than they would if homogeneity were forced upon them.

From territories as expansive as the nation-state to those as localised as the classroom, the most powerfully inclusive senses of belonging are created when differences are recognised, productively used, and seen to be to everybody’s advantage. For the nation, or the enterprise, having a diverse membership creates links into diasporic networks and markets and provides the benefits of a broad variety of experiences and perspectives. In the classroom, students can learn from each other’s differences – of perspective, experience, subject matter knowledge and ways of thinking. Their differences become a learning resource. And if all the learners in a classroom feel they belong in their difference – that the learning environment values and uses their different knowledge and perspectives – then this learning will be so much more powerful. Try to ignore the differences, and many learners will feel less comfortable about their relationship to what is being taught and to other learners.

The paradox of belonging is that if you are to live more comfortably in the mainstream, that mainstream must recognise your difference and regard that difference as one of the mainstream’s strengths and resources. But by this time, the mainstream – from the narrative of the nation to the lesson in a classroom – has transformed itself into something that is open and pluralistic in character. By the time the story of this kind of nation finds its way into the classroom, it will have become the stories in the plural – of different cultural groups and their fruitful collaborations, and of struggles for democracy and rights, including, at times, heroic acts of inclusion.

See Verran Observes a Mathematics Classroom in Africa.

Language

The paradoxical dynamic of globalisation – of deeper interconnectedness at the same time as increasing divergence – offers new hope to small languages. The possibility arises, for instance, of recording and making accessible language instruction, oral histories and literature through the Internet. The digital communications revolution makes this cheaper and logistically easier than at any time in the past. At the same time, the educational reasons to do this become more insistent. Mother-tongue language learning affirms and builds upon a child’s home language and cultural background. Strategies to cater for small and dispersed languages include online learning and after-school or weekend schools run by language communities themselves. The spread of English as the global lingua franca does not have to mean reduction in language diversity.

Even the dominant global language, English, changes. On the one hand, for the majority of its speakers, English becomes a pragmatic language of global interchange and communication of knowledge rather than a language of identity. On the other hand, English becomes fragmented into hybrid and unstable forms that are less mutually intelligible, including the creoles of post-colonial societies, the dialects of urban ghettoes, the arcane vernaculars of divergent youth cultures, the specialist discourses of experts and the technicalese of sports and hobbies. Language is in a dynamic state of divergence.

The social response to multilingualism is varied. It includes the use of graphemes rather than phonemes – the male or female symbol that is pronounced ‘toilet’ by Australians and ‘rest room’ by Americans. Multilingual interfaces mean that when you get to the ATM, you can choose your own language. Improved technologies of machine translation make any website or electronic document roughly intelligible regardless of the source language. Multilingual call centres mean that if you are a Greek speaker and you have lost your credit card in the backwoods of Argentina, you can still speak to a bank officer on the phone in Greek (Cope and Gollings 2001).

How do we address the tendency to divergence within a language like English? In public life, we need to switch quickly and often between one social language in one dis- course community and another. In each place we need to speak like (and act like and feel like) that community. When we don’t quite get what is being said, or the other per- son does not quite get us, the old literacy of correct usage and rules leaves us stranded. There is no point in suggesting to the other person that they speak properly because there is no single ‘properly’ any more – there is only aptness to situation. So, instead of teaching language learners the rules, we need to teach them the ‘multiliteracies’ techniques of contrastive linguistics: how do we make sense of the differences in meanings we encounter, and how do we create reader- and listener-aware communications? (Cope and Kalantzis 2009)

Gender

Now we find the unequal gender relations of earlier modern times in a process of transformation. This is, in part, a consequence of a century of activism in the feminist movement. A first wave of feminists struggled for formal legal rights, notably female suffrage, or the right to vote. The next wave fought for economic equality, the right to work and earn equal pay to men in comparable jobs. They insisted on equality at home, so the biology of reproduction did not so closely tie women to childrearing. Domestic work was to be shared by men and women. More recent feminists have criticised the idea of the ‘liberated woman’ because they think that it is sometimes too closely aligned to a middle-class, white, professional ideal. They want to acknowledge the many and varied experiences of women – in the developing as well as the developed world, among diverse cultural groups, or according to sexual orientation, for instance. According to the proponents of this wave of feminism, there can be no single model or ideal for liberated femininity.

There is also today more vocal disagreement about gender roles than ever before. Religious fundamentalists stridently argue that traditional differences in roles are ordained by God and nature. Activists, meantime, argue that there is no single path to redressing the inequalities created by sexism. In fact, a clear separation of gender roles and identities is at times justified as a means to empowerment or as a social ideal. Feminist groups and women’s career networks at times exclude men in order to build a strategy for access into domains in which men still dominate. Arguments for all-girl secondary schools are frequently mounted, the case being that adolescent girls do better in environments in which they do not have to compete with boys (Datnow and Hubbard 2002). Some Muslim women argue that gender-role differentiation creates space for a flourishing community of women, and that modest women’s clothing reduces women’s exposure as sexual objects.

The variety and range of expressions of gender identity linked to sexuality have also expanded greatly in recent times. Although the case is widely made that sexuality is a matter of corporeal or biological inheritance, there is no one-to-one relationship between sexuality and gender identities. There are heterosexual as well as homosexual men who do body building to accentuate their masculinity, and ‘metrosexuals’ who are heterosexual but assume what might be considered a somewhat effeminate persona. Lesbians may be butch or femme. Trans-gender people may retain their original sex but cross-dress and take on the persona of the opposite sex. This need not be connected with their sexual orientation, which may be heterosexual or homo-sexual or bisexual. Intergender people may not want to define their gender clearly, or may want to be able to express themselves through different gender symbolism at different times. There is also widespread androgyny, or ambiguity created by the mixing of gender characteristics.

Sex, sexuality and gender identities are clearly closely interrelated, to the extent that the separation of corporeal and symbolic realities suggested by the sex/gender distinction today seems far too simplistic. We propose the word ‘gendre’ to describe the complex range of differences that now manifest themselves in the close interplay of sex, sexuality and gender – often to the point where it is hard to make an analytical distinction between sex and gender. We use this word from Middle English because, although it is the root of the modern word gender, it has a wider meaning derived from its Latin source, genus, and Old French source, gendre. In these original languages and uses, ‘gendre’ means ‘kind’ or ‘type’ – a meaning that continues today in another derivative word, ‘genre’. However, we want to give the word ‘gendre’ a particular meaning, using it to describe a person’s kind of corporeal and symbolic being created in the intersection of sex, sexuality and gender.

The enormous variety and subtle complexity that is ‘gendre’ may suggest social chaos, fragmentation and uncertainty about the relationships between sex, sexuality and gender, which once seemed so clear. Adolescents emerging to sexual maturity and having to define adult gender roles for themselves may experience this as an emotional roller-coaster. Parents and peers are often ill-prepared to deal with gendre diversity and change, now so pervasive in the lifeworlds of young people. How do parents and educators address the personal choices so readily available to young people, a world of identity and lifestyle alternatives where there are no unequivocal models of normality? This is the case as much as anything for those who vehemently choose traditional roles of sex, sexuality and gender. The sheer range of symbols and practices referred to by the concept of gendre expands daily, it seems, and the alternatives are ever more visible. The insistent public expression of gendre difference, diversity and divergence is one of the key characteristics of contemporary youth scenes. Schools, particularly secondary schools, have to deal with all of this today.

See Connell on Changing Gender Roles.

Affinity and persona

The range of lifeworld experiences today is broader than was ever the case in an earlier modernity – differences in life history, interest, affinity, group membership, peer culture and sub-culture, to name just a few variables. Two instances of this dynamic will suffice: the influence of media and markets.

With its handful of newspapers, radio stations and TV channels, the mass media of earlier modernity created common culture for national audiences, even if perhaps artificially and against the grain of different lived experiences and actual histories. In recent times, things have become complex. The new media consist of a myriad of newspapers, magazines and blogs accessible through the Internet or reading tablets; thousands of satellite cable TV channels, tens of thousands of radio stations available through satellite or the Internet, and billions of websites. No two social media feeds are the same. The less-regulated, multi-channel media systems of today undermine the concept of collective audience and common culture. Instead, it promotes the opposite: an increasing range of accessible, sub-cultural options supporting increasingly divergent specialist and sub-cultural discourses. This spells the definitive end of ‘the public’ – that homogeneous imagined community of the nationalist state.

Some of this change is the result of new technological possibilities; ‘narrow- casting’ to finely targeted audiences, or ‘pointcasting’ to customised syndication feeds or social media update streams. These changes, however, are by no means solely a iat of technological change. Cultural divergence is at the root of these changes. The result: customisation of personal media according to affinity groups defined by ethnicity or language, indigenous origins, sexual orientation, gender politics, ethical concern, domain of expertise, hobbyist fetish, proclivities for consumption, fashion, fad, taste or personal style. Each creates communities that communicate in distinctive ways. With the collapse of the homogenising cultural processes of earlier modernity, discourses of sub-cultures progressively become more divergent, and thus less mutually intelligible and harder for outsiders to get into. Yet, at the same time as this fragmentation is occurring, divergent sub-cultures find themselves juxtaposed in more intimate ways within workplaces, neighbourhoods and communications media.

Another area of profound change is the market. In an earlier capitalism, people consumed generic commodities, mass-produced products deemed by the entrepreneurs and their designers to be what the consumer needed. The new consumerism tangles deeply with people’s divergent identities – the family market, the single- women’s market, the gay men’s market, various ethnic markets, generational markets or markets based on occupational profile. Anyone who works in the advertising industry today is able to slice and dice potential markets according to any number of demographics. More deeply than ever before, this is a cultural play that engages identities in the poignantly and emphatically plural.

Reversing the older logic of mass consumption, markets today are undergoing a process of increasing sub-cultural fragmentation around divergent ‘niches’. From the affluent end of the spectrum of consumption towards its middle and even its cheaper end, we find a proliferation of ‘boutique’ products and services, drenched in identity- differentiating commodity aesthetics. At the cheapest end of the spectrum, the working poor and welfare recipients may find at times that they have no alternative but to consume generic products. Or they may have to buy second-hand cast-offs. However, even the less affluent at times find themselves close enough to the nether regions of niche identity consumerism to be seduced by its promises.

Today we live in more and more narrowly defined communities, but also in many more of them – media-defined, consumerist, workplace, ethnic, sporting, sexual- preference, religious, hobby-interest – and the sum-total extent of these many communities for any one person is often enormous. The paradox is that, despite the seeming descent into social fragmentation, we end up being more connected than ever. We are simultaneously members of multiple lifeworlds. Our identities have multiple layers in complex relation to each other. No person is a member of a singular community. Rather, they are a member of multiple and overlapping communities. In each of these communities, they find they are a different kind of person, interacting in a different kind of way. And because, over the course of a week, or a day or even an hour, they belong to many communities, their identity becomes multilayered, their personality multiple. A person’s self has many sources.

Language, discourse and register are among the many markers of these lifeworld differences – ways of speaking that reflect ways of thinking and acting. As lifeworlds become more divergent and their boundaries more blurred, the central characteristic of our meaning-making becomes the multiplicity of these meanings and their continual intersection. A teacher speaks professional teacher-talk to another teacher, but translates this into teacher–parent talk in a parent–teacher interview. Their way of speaking in this context is very different from what it would be in the many other social and cultural contexts in which they circulate. Just as there are multiple layers to everyone’s identity, there are multiple discourses of identity and multiple dis- courses of recognition to negotiate. We have to be proficient as we negotiate the many lifeworlds each of us inhabits, and the many lifeworlds we encounter in our daily lives.

The paradox is that the more society appears to be breaking up into communities unto themselves, the more sociable we seem to become, the greater the number of these communities that each of us belongs to, and the greater the extent of their reach, from the finely localised to the broadly global. You can meet somebody and soon find out many things unfamiliar and distant about who they are. Then, in the next breath, you find surprising points of common experience, interest or aspiration. This is a common everyday experience in this era of civic pluralism and total globalisation.

See Kalantzis and Cope, Seven Ways to Address Learner Differences.