Social cognitivism: Towards New Learning

A social-cognitivist approach to the question of learning attempts to balance social and cultural factors with the potentialities of the brain. Social cognitivists want to develop a fuller account of the ‘nurture’ side of the nature-plus-nurture mix. Of course, theorists on both sides of the nature-nurture debate agree that an enormous amount is learned in a social context by means of the processes of socialisation. The main point of disagreement is the mix – how much learning is social, and how much is biologically based.

See Social Cognitivism Case Studies.

Dimension 1: The processes of learning

Human learning is social, in ways that are different from any other animal learning. More than any other creature, humans are what they have learned. Babies are immersed in oral language. They learn the words for things, and languages that put these words together into frameworks for meaning. They come to understand the world through the way in which language means the world. Language is not just the stuff of communication with others. It is a conceptual tool with which one represents the world to oneself. It is as though one were to understand things at least in part by talking to oneself. This process of meaning making is called ‘representation’.

As well as language, babies are immersed in sights, images and scenes. They learn to make sense of this perceptual field, to see the world in ways that are characteristic of the images and sights of their lives, to develop a kind of mind’s eye in which the world can be visualised in meaningful ways. As they direct their attention to the world, they learn to make sense of patterns of colour and light as meaningful visual percepts. They also learn to make sense of the sounds of their environment, to hear things in meaningful ways – noises, music, alerts and the like. They learn the bodily meanings of touch, smell and taste. They learn to gesture and to understand gestures. And they learn how to read and make sense in and of space – interpersonal, architectural and environmental. In each case, we acquire from our cultures the means of meaning, the raw materials with which we make sense of the world. Unlike any other creature, these means form into a system of symbols (Kalantzis and Cope 2012b).

The Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky describes children’s transition from what he calls ‘complex’ to ‘conceptual’ thinking through the social process of language acquisition. Children’s developing capacity to think is embodied in the structures of language. Through language learning, children undergo a parallel and complementary process of social and cognitive development. Children learn in a social context, in which meanings are irst framed interpersonally in social interaction. Only later is the full depth of these meanings realised intrapersonally or within the individual mind (Vygotsky 1934).

See Vygotsky on Language and Thought.

This process is integrally connected with the human language inheritance, and other complementary and uniquely human and related modes of symbolic representation – image, sound, gesture, touch and space. Animals communicate, and presumably represent the world to themselves, by creating relationships between sound or gesture and events or emotional states, such as fear and satisfaction. These are one-to-one resemblances, a kind of ‘pointing at’ some thing or event, which is sometimes called ‘indexical’ representation or communication (Donald 2001).

Human symbol systems, by contrast, connect signs with each other to form structures of meaning that have a life of their own. Babies may start with words whose meanings are not unlike the indexical type of meaning (the word ‘points at’ something) of which some animals are also capable. But they soon pick up the enormous flexibility and generativity of the human symbol-making systems of language, image, sound, touch, gesture and space. In these systems, symbols do not just relate to the thing they are pointing at. They also relate to each other, forming structures or systems of symbol-to-symbol relationships.

As these systems develop in the growing young human, the meanings become more and more profound. Vygotsky describes the transition from words whose relationship to meaning is what he calls a ‘complex’ to words that, in the older child, have become the basis for ‘conceptual’ thinking. Children may use words when they are young, but not ‘get’ their full meaning until they are older and their thinking has developed (Vygotsky 1978).

See Deacon on the Symbolic Species.

Dimension 2: The sources of ability

All animals learn, even animals with cognitive capacities as limited as a fruit fly. But humans learn more than any other animal. They have to learn so much in order to become fully contributing adults in the species. Their inherited biology provides less of a guide than any other creature. It is humans’ learning capacity – in fact, the sheer breadth and depth of the necessity to learn – that distinguishes them so dramatically from every other creature in the natural world. Human babies have so little to go by when they are born that they are helpless and dependent in a way no other animal is.

See Christian Explains the Uniqueness of the Learning Species.

The key question, then, is how much of what we know is innate and how much is learned? Certainly, many involuntary reactions and emotions are innate. But is language innate? As mentioned earlier in this chapter, some theorists, such as Chomsky and Pinker, argue that language is so complex and learned so quickly that its under- lying structures (as distinct from the particular language we happen to speak) must have become part of humans’ biological inheritance. Other theorists we have mentioned – including Vygotsky, Donald, Deacon and Gee – argue that language is learned and that the baby’s brain has a remarkable capacity to learn modes of symbolic representation.

See Donald on the Evolution of Human Consciousness.

Human representational and cognitive capacities are essentially a cultural inheritance. In this view, the fully functioning human brain is co-constructed by the baby, using resources for meaning supplied from the surrounding culture. In fact, we now know that learning even transforms the biological structure of the developing person’s brain.

How, then, does one account for the sources of human ability? In the social-cognitivist view, nature provides humans with a range of ‘affordances’. Nature does not provide a blueprint, but a series of potentialities that are filled to a substantial degree by the socio-cultural cognition that is our cultural inheritance. Being external to the individual brain, this is necessarily acquired through learning. This is how nurture allows us to fill out the potentialities provided by our human-physiological nature.

See Gee on Situated Cognition.

Dimension 3: Infrastructure for learning

You are as smart as your surroundings – what you have learned from your environment, the knowledge sources you can draw upon, the physical and cognitive tools you can draw upon, and the other people with knowledge whom you can rely upon when you need them (Salomon 1993; Gazzaniga 1988).

By choosing to regard our human nature as an affordance, our focus accounts for the ways in which nurture gives substance to nature’s offerings. We need to know about nature, to be sure, because that helps us explain the fertile physiological ground upon which nurture grows our humanity. But the really hard and important questions for educators are about nurture. This is where we can reliably explain human differences. It is also where we can act or intervene to improve or change the conditions of learning. Biology, on the other hand, is much more determined and determining, be that a measure of ‘innate intelligence’, a ‘stage of development’ or a ‘language instinct’. When we choose to attribute biological sources to a human characteristic, we are allowing that there is less we can do; even, perhaps, that there is even less that we should try to do. When we interpret the sources of that characteristic to be socio-cultural, there are things we can and often must do. Sometimes these things may be practically hard to do. Difficult though it may sometimes be, you can always do something to improve socio-cultural conditions.

So, when we take as our starting point an assumption about the open affordances of the human brain, our focus shifts to the cultural conditions that provide different opportunities to learn and that also explain differential educational and social outcomes. This approach also makes sense in terms of the limited extent of contemporary knowledge of the brain. Until neuroscience can tell us more about the physiological functioning of consciousness and learning, the social cognitivists should at the very least give educability the benefit of the doubt. As we can always do something to improve the social conditions of learning, let’s assume that socio-cultural intervention could have an impact. Let’s try to do what we can to improve opportunities.

See Honderich on Consciousness.

If cognition is social, then the most powerful learning is collective rather than individual. Education exercises an individual’s capacity to learn in and with the people and the knowledge resources that are around them. ‘Situated learning’ in a ‘community of practice’ are keys to this conception of learning (Lave and Wenger 1991). Education is not an individualised, psychological-cognitive thing. Rather it is a set of relationships with others in a knowledge or learning community.

See Wenger on Learning in Communities of Practice, and Lave and Wenger on Situated Learning.

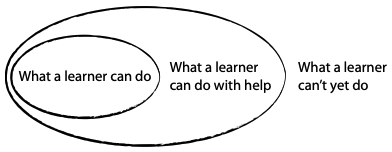

This learning is far from incidental or accidental. The offspring of other animals learn things from more experienced members of the group into which they are born. No creature other than humans, however, teaches its young via a process of conscious pedagogy. Other creatures may learn from adults, but only by being with and observing adults – not because the adults have set out to teach them. The parents of young children, teachers in schools, mentors in workplaces and the authors of help menus teach the novices they encounter in a premeditated way not to be found in any other species. They push the learners they encounter beyond what they already know, but within the bounds of what they as the teacher know is knowable for them, based on their pre-existing knowledge. Vygotsky calls this their Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky 1978).

The result is that the knowledge in a person’s head is much more than just that. It is a social cognition, the very shape of which is given by shared cultural inheritance. This is inherent in our means of representation (making sense of the world for ourselves) and communication (passing that sense on to others), including language, gesture, visualisation and spatial navigation. All of these meaning-making capacities have to be learned. We also rely on knowledge we can’t know but nevertheless need – the experts we depend upon either implicitly or explicitly when we ask for help (mothers, teachers, doctors, engineers), the tools we use that we could not have created for ourselves (physical, conceptual), and our symbolic legacy in the form of knowledge that we always know we can ‘look up’ as and when needed.

See Salomon on Distributed Cognition.

This, then, provides the foundation for an educational agenda for New Learning. Learning, in the social-cognitivist view, is not only or mainly a product of brain development. In fact, brain development would not happen without learning. Intelligence does not come from the brain. Intelligence is in the genius of our socio-cultural inheritance. Our brains happen to have been open to that inheritance. Cognition happens as much outside of the brain as it does inside. It finds fertile ground in the open potentialities of the brain, and so shapes the brain. The transformative task of education is to support this learning process.

Dimension 4: Measuring learning

The social-cognitivist approach to learning leaves more scope for differences, and thus broadens the range of measures of learning. One consequence of this deep sociability of learning is the sheer diversity of alternative ways of being. The range of alternatives is not available for creatures without symbol systems or social processes of conscious pedagogy. You are what you learn to mean, and as the learning context varies, so do you. Take as an extreme case the rare times when developing humans who have survived outside of society show the extraordinary range of human potential. Particularly revealing are the bizarre stories of ‘feral children’, such as children who became quite like wolves in some respects because they lived with wolves for a time (Candland 1993).

See The ‘Wolf Children’ of Godamuri.

Cultural and linguistic differences cross a broad range. Learning will vary enormously according to social needs and interests. This means that the aims and institutions of education need to vary just as much.

See Marika and Christie on Yolngu ways of Knowing and Learning.

Even within a particular social setting, teachers will encounter many different kinds of intelligences or ‘learning styles’. Monocultural, didactic approaches to education historically favoured certain learning styles over others. Certain ways of thinking, speaking and points of view were adjudged ‘successful’, while others were condemned to ‘failure’. Educators have attempted to develop alternative ways of conceiving intelligence and learning in order to alleviate the exclusionary effects of this kind of approach to education. For instance, Howard Gardner argues that there is not one intelligence, but many and varied forms of intelligence, some of which we may become better at than others in different circumstances of learning (Gardner 2006).

See Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences.

In a social-cognitivist view, learning is a product of social circumstances rather than a biological code written into an individual’s brain. As a learner’s circumstances vary, so does the nature and substance of their human ability. Social cognitivists speak of the affordances of the brain, and the multiple and varied abilities that happen to be nurtured by the intelligence that is around the learner. For this, multiple and varied measures of learning are required.