Yan Pho Lee’s School Days

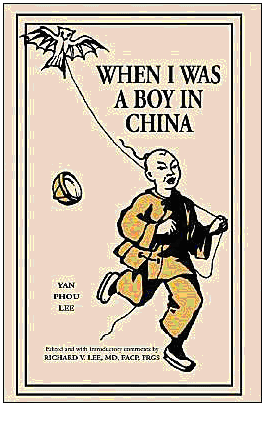

Yan Pho Lee arrived as an immigrant from China in San Francisco in 1873. In 1887 he wrote a book, When I was a Boy in China in which he described his school days.

Here he describes the intersubjective relations in a 19th century classroom in China:

The schoolmaster in China must be absolute. He is monarch of all he surveys; in his sphere there is none to dispute his rights. You can always point him out among a thousand by the scholar’s long gown, by his stern look, by his bent form, by his shoulders rounded by assiduous study. He is usually near-sighted, so that an immense pair of spectacles also marks him as a trainer of the mind. He generally is a gentleman who depends on his teaching to make both ends meet—his school is his own private enterprise—for no such thing exists in China as a “school-board,”—and if he be an elegant penman, he increases the weight of his purse by writing scrolls; if he be an artist, he paints pictures on fans …

A tuition fee in China varies according to the ability and reputation of the teacher, from two dollars to twenty dollars a year. It varies also according to the age and advancement of the pupil. The older he be, the more he has to pay …

Schools are held either in a private house or in the hall of a temple. The ancestral temples which contain the tablets of deceased ancestors are usually selected for schools, because they are of no other use and because they are more or less secluded and are generally spacious. In a large hall, open on one side towards a court, and having high ceilings supported by lofty pillars beside the brick walls, you may see in the upper right-hand corner a square wooden table, behind which is the wooden chair; this is the throne of his majesty—the schoolmaster. On this table are placed the writing material consisting of brushes, India ink, and ink-wells made of slate. After pouring a little water in one of these wells the cake of ink is rubbed in it until it reaches a certain thickness, when the ink is ready to be used. The brushes are held as a painter’s brushes are.

In conspicuous view are the articles for inflicting punishment; a wooden ruler to be applied to the head of the offender and sometimes to the hands, also a rattan stick for the body. Flogging with this stick is the heaviest punishment allowed; for slight offences the ruler is used upon the palms, and for reciting poorly, upon the head …

I began to go to school at six. I studied first the three primers: the “Trimetrical Classic,” the “Thousand-words Classic,” and the “Incentive to Study.” They were in rhyme and meter, and you might think they were easy on that account. But no! they were hard. There being no alphabet in the Chinese language, each word had to be learned by itself. At first all that was required of me was to learn the name of the character and to recognize it again. Writing was learned by copying from a form written by the teacher; the form being laid under the thin paper on which the copying was to be done. The thing I had to do was to make all the strokes exactly as the teacher had made them. It was a very tedious operation. I finished the three primers in about a year, not knowing what I really was studying …

I then took up the “Great Learning,” written by a disciple of Confucius, and then the “Doctrine of the Mean,” by the grandson of Confucius. These text-books are rather hard to understand sometimes, even in the hands of older folks; for they are treatises on learning and philosophy. I then passed on to the “ Life and Sayings of Confucius,” known as the “Confucian Analects “ to the American scholars … I had to learn all my lessons by rote; commit them to memory for recitation the day following … All studying must be done aloud. The louder you speak or shriek, the more credit you get as a student. It is the only way by which Chinese teachers make sure that their pupils are not thinking of something else or are not playing under the desks.

Now let me take you into the school where I struggled with the Chinese written language for three years. Oh! those hard characters which refused to yield their meaning to me. But I gradually learned to make and to recognize their forms as well as their names. This school was in the ancestral hall of my clan and was like the one I have described. There were about a dozen of us youngsters placed for the time being under the absolute sway of an old gentleman of three core-and-six …

It is 6 A.M. All the boys are shouting at the top of their voices, at the fullest stretch of their lungs … All at once the talking, the playing, the shouting ceases. A bent form slowly comes up through the open court. The pupils rise to their feet. A simultaneous salutation issues from a dozen pairs of lips. All cry out, “Lao Tse” (venerable teacher)! As he sits down, all follow his example … Then one takes his book up to the teacher’s desk, turns his back to him and recites. But see, he soon hesitates; the teacher prompts him, with which he goes on smoothly to the last and returns to his seat with a look of satisfaction. A second one goes up, but, poor fellow, he forgets three times; the teacher is out of patience with the third stumble, and down comes the ruler, whack! whack! upon the head. With one hand feeling the aching spot and the other carrying back his book, the discomfited youngster returns to his desk.

Lee, Yan Pho. 1887 (1914). “When I was a Boy in China.” Pp. 214–221 in The World’s Story: A History of the World in Story, Song, and Art, edited by Eva March Tappan. Boston MA: Houghton Mifflin. || Amazon || WorldCat