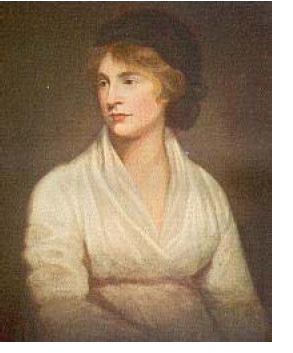

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) was an English philosopher, writer and early advocate of women’s rights, who took Rousseau to task for his views on the role of women in society and their education. Wollstonecraft makes an early case for gender equality:

This is certainly only an education of the body; but Rousseau is not the only man who has directly said that merely the person of a young woman, without mind, unless animal spirits come under the description, is very pleasing. To render it weak, and what some may call beautiful, the understanding is neglected, and girls forced to sit still, play with dolls and listen to foolish conversations; the effect of habit is insisted upon as an undoubted indication of nature …

Rousseau declares that a woman should never, for a moment, feel herself independent, that she should be governed by fear to exercise her natural cunning, and made a coquettish slave in order to render her a more alluring object of desire, a sweeter companion to man, whenever he chooses to relax himself. He carries the arguments, which he pretends to draw from the indications of nature, still further, and insinuates that truth and fortitude, the corner stones of all human virtue, should be cultivated with certain restrictions [for men only, leaving out women], because, with respect to female character, obedience is the grand lesson which ought to be impressed with unrelenting rigour …

It is vain to expect virtue from women till they are, in some degree, independent of men; nay, it is vain to expect that strength of natural affection, which would make them good wives and mothers. Whilst they are absolutely dependent on their husbands they will be cunning, mean, and selfish, and the men who can be gratified by the fawning fondness of spaniel-like affection, have not much delicacy …

I firmly believe, that all the writers who have written on the subject of female education and manners … have contributed to render women more artificial, weak characters, than they would otherwise have been; and, consequently, more useless members of society …

Contending for the rights of woman, my main argument is built on this simple principle, that if she be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge and virtue; for truth must be common to all, or it will be inefficacious with respect to its influence on general practice. And how can woman be expected to co-operate unless she know why she ought to be virtuous? Unless freedom strengthen her reason till she comprehend her duty, and see in what manner it is connected with her real good? If children are to be educated to understand the true principle of patriotism, their mother must be a patriot; and the love of mankind, from which an orderly train of virtues spring, can only be produced by considering the moral and civil interest of mankind; but the education and situation of woman, at present, shuts her out from such investigations …

[N]ot only the virtue, but the knowledge of the two sexes should be the same in nature, if not in degree, and … women, considered not only as moral, but rational creatures, ought to endeavour to acquire human virtues (or perfections) by the same means as men, instead of being educated like a fanciful kind of half being- one of Rousseau’s wild chimeras. Is one half of the human species, like the poor African slaves, to be subject to prejudices that brutalize them … ? Is not this indirectly to deny woman reason? …

I, therefore, will venture to assert, that till women are more rationally educated, the progress of human virtue and improvement in knowledge must receive continual checks … The mother, who wishes to give true dignity of character to her daughter, must, regardless of the sneers of ignorance, proceed on a plan diametrically opposite to that which Rousseau has recommended …

Wollstencraft, Mary. 1792. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. London: J. Johnson. pp. 99–100, 103, 37–38, 174, 33, 8, 53, 178, 55–56. || Amazon || WorldCat