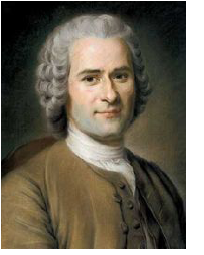

Jean-Jacques Rousseau on Emile’s Education

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–88), one of the most important social and political philosophers of modern times, wrote a book on education which described the way he would educate an imaginary boy, Emile. The education Rousseau recommended for Emile’s wife-to-be, Sophy, is presented in Chapter 5. Rousseau was one of the first modern thinkers to suggest a more natural or authentic alternative to didactic education:

Plants are fashioned by cultivation, man by education. If a man were born tall and strong, his size and strength would be of no good to him till he had learned to use them; they would even harm him by preventing others from coming to his aid; left to himself he would die of want before he knew his needs. We lament the helplessness of infancy; we fail to perceive that the race would have perished had not man begun by being a child. We are born weak, we need strength; helpless, we need aid; foolish we need reason. All that we lack at birth; all that we need when we come to man’s estate, is the gift of education.

This education comes to us from nature, from men or from things. The inner growth of our organs and faculties is the education of nature, the use we learn to make of this growth is the education of men, what we gain by our experience of our surroundings is the education of things. Thus we are each taught by three masters … Now of these three factors in education, nature is wholly beyond our control, things are only partly in our power; the education of men is the only one controlled by us; and even here our power is largely illusory, for who can hope to direct every word and deed of all with whom the child has to do …

If children are not to be required to do anything as a matter of obedience, it follows that they will only learn what they perceive to be of real and present value, either for use or enjoyment; what other motive could they have for learning? The art of speaking to our absent friends [through learning to write], of hearing their words [by learning to read]; the art of letting them know at first hand our feelings, our desires, and our longings, is an art whose usefulness can be made plain at any age. How is it that this art, so useful and pleasant in itself has become a terror to children? Because the child is compelled to acquire it against his will, and to use it for purposes beyond his comprehension. A child has no great wish to perfect himself in the use of an instrument of torture, but make it a means to his pleasure, and soon you will not be able to keep him from it. People make a great fuss about discovering the best way to teach children to read. They invent ‘bureaux’ and cards, they turn the nursery into a printer’s shop. Locke [the philosopher, quoted in Chapter 6] would have them taught to read by means of dice. What a fine idea! And the pity of it! There is a better way than any of those, and one which is generally overlooked—it consists in the desire to learn. Arouse this desire in your scholar and have done with your ‘bureaux’ and your dice-any method will serve …

As to my pupil [Emile], permit me to prevent him studying any of [these things] till you have convinced me that it good is for him to learn things three-fourths of which are unintelligible to him … When I get rid of children’s lessons, I get rid of the chief cause of their sorrows, namely their books. Reading is the curse of childhood, yet it is almost the only occupation you can find for children. Emile at twelve years old, will hardly know what a book is … When reading is of use to him, I admit he must learn to read, but till then he will only find it a nuisance …

Work or play are all one to [Emile], his games are his work; he knows no difference. He brings to everything the cheerfulness of interest, the charm of freedom, and he shows the bent of his own mind and the extent of his knowledge. Is there anything better worth seeing, anything more touching or more delightful, than a pretty child, with merry, cheerful glance, easy contented manner, open smiling countenance, playing at the most important things, or working at the slightest amusement? …

Teach your scholar to observe the phenomena of nature; you will soon rouse his curiosity, but if you would have it grow, do not be in too great a hurry to satisfy this curiosity. Put the problems before him and let him solve them himself. Let him know nothing because you have told him, but because he has learnt it for himself. If ever you substitute authority for reason he will cease to reason, he will be a mere plaything of other people’s thoughts …

Let us transform our sensations into ideas, but do not let us jump all at once from the objects of sense to objects of thought … Let the senses be the only guide for the first workings of reason. No book but the world, no teaching but of fact. The child who reads ceases to think, he only reads. He is acquiring words not knowledge.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1762 (1914). Emile, or Education. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. pp. 6, 81, 80–81, 126, 131. || Amazon || WorldCat