Education assessment, evaluation and research

In public debates about the future of education, the question of measuring learning figures prominently. How much feedback do students get about their learning, and how useful is it? How do parents know how well their children are doing at school? How do we know how well teachers are teaching? How do we know whether one pedagogical approach, curriculum design or institutional setup in an education community is better than any other, and how do we get the information we need to choose amongst alternatives? How do we know whether the resources being put into education are well spent? Could they be spent better? How do we know what works to produce learning. Can educational measurement be an exact science?

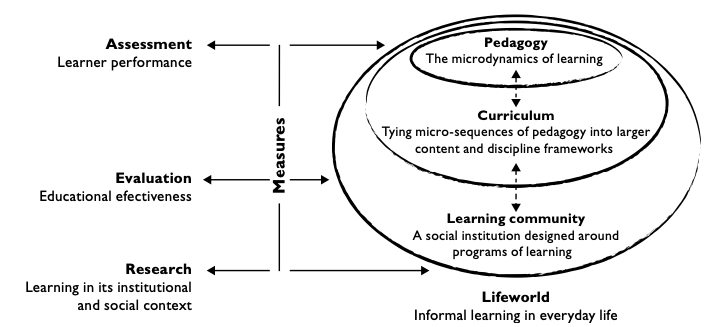

In this chapter we explore three dimensions of educational measurement:

- dimension 1: assessment–or how learner performance is measured

- dimension 2: evaluation–or how the effectiveness of an educational program or curriculum is measured

- dimension 3: research–or how the effectiveness of education interventions are measured in the context of their community settings.

Assessment investigates the details of student learning for the following purposes:

- to find out what a learner already knows so what they are taught is appropriate to their needs (diagnostic assessment)

- to provide as-you-go feedback so the teacher and learner can see what the learner is learning and what they still need to learn, while they are learning (formative assessment)

- to provide at-the-end reporting so the teacher, learner and parent can see how well the student has performed on the measure of the intended learning outcomes (summative assessment).

Evaluation takes a step back to find out:

- how well a curriculum or an educational program has worked in terms of its stated goals and, as a part of this, how well the teacher has designed and implemented the curriculum or program according to these expectations

- how effective a school is, as measured by the educational objectives it has set itself or by some other official body.

And, of course, the assessment results will often be an important part of the evaluation process.

Research takes a further step back from the educational scene in order to take one of two stances. These stances have particular methodologies that are regarded as scientific because of their deliberate objectivity, rigour and use of multiple tools and perspectives to ensure validity. The two stances are:

- systematically observing the processes at work in a learning community and the outcomes they produce. This might be an holistic view of a whole school or a fine-grained analysis of a pedagogical approach or a curriculum. But no matter how finely focused, research always has to take into account the institutional dynamics of the learning community and the lifeworld context of its learners.

- actively intervening, and designing and implementing an educational innovation, and then measuring its effectiveness. Once again, no matter how specifically focused, research always has to take as its reference point effectiveness in the context of the whole learning community, and of that learning community in the broader society.

And, of course, both assessment results and evaluation outcomes will often provide valuable research evidence.

Today, every teacher needs to consider all three of these levels of measurement to be essential parts of their professional repertoire: assessment, evaluation and research. These measurement practices make teachers systematically alert to the conditions in their environment. Using the methods of assessment, evaluation and research, teachers position themselves as educational knowledge makers. These practices of learning science become an essential part of their professional repertoire. In this sense, teachers today are also learners, using the data they have collected from assessments, evaluation and research to drive their decisions about teaching and learning. But it wasn’t always this way, or at least not in any systematic way. Until recently, teachers often did little more in the way of measurement than implement assessments required of them by textbooks, the school, the state and other external test-setting bodies.