Measurement by standards: More recent times

Dimension 1: Assessment

A large change happens in the measurement of learning as a part of the paradigm shift in education from didactic to authentic pedagogy that we have been describing in this book. One aspect of this change is the move away from intelligence testing and testing of memory of factual curriculum contents to assessment of standards. This shift occurs in the last quarter of the 20th century, and by the second decade of the 21st century, standards are nearly universal as the basis for educational measurement (Fuhrman 2001). This is not to say that we don’t still have a lot of educational measurement that looks like the memory tests of old, nor that we don’t still have a long way to go in a journey that takes us to a new place that we want to call ‘synergistic feedback’. But we want to say that, even though many of the tests look much the same as they always have, the paradigm shift is a deceptively large one.

Here we are doing geography in Year 4, with the content-focused approach of didactic teaching and educational measurement. The Department of Education has a syllabus that prescribes ‘The Rivers’ as a topic for the second term of this year. So, when the time comes, the teacher asks their students to open their geography textbooks at Chapter 6, ‘Our Rivers’. They read the chapter, answer a quiz at the end, then just before the end-of-term geography test they memorise the order of the rivers along the coast. They do a test, one of whose questions is which river is between River B and River D. Four alternatives are provided: Rivers A, C, E and X. And, of course, if you know your geography the answer is River C.

Now, here we are doing geography in a standards-based approach. The standards for Year 4 include: ‘can understand and apply landform concepts related to water resources’. The teacher has the students look up information about river systems; asks the students to define a river system; draw a map of the river system in their country; and write a project about one river system, including critical challenges, such as access to water resources and pollution. The students are then marked by the teacher on the quality of their projects – how well they have collected facts, applied geographical concepts and reflected on challenging issues raised by river systems. If they are to have a test at the end, it focuses on problem solving and clarifying concepts, less than remembering facts (Darling-Hammond, Ancess, and Falk 1995).

See Darling-Hammond et al. on Authentic Assessment.

|

THE CONTENT APPROACH OF DIDACTIC PEDAGOGY |

THE STANDARDS APPROACH OF AUTHENTIC PEDAGOGY |

|

|

Systems expectations |

The syllabus lists the contents that are to be taught, and what is to be tested |

General descriptions of intended learning outcomes: performance, disciplinary and knowledge outcomes |

|

Curriculum resources |

Textbooks following the syllabus, chapter by chapter |

A mix of resources |

|

Teacher role |

The teacher walks the class through |

The teacher designs learning activities through which the learners develop the skills and grow the knowledge described in the standards |

|

Learner role |

The student memorises the content of the textbook: facts, definitions and rules |

The student is a more active learner |

|

Assessment |

The learner demonstrates their memory of the content of the curriculum |

Tests are more oriented to demonstrations of problem solving, thinking skills and disciplinary understanding |

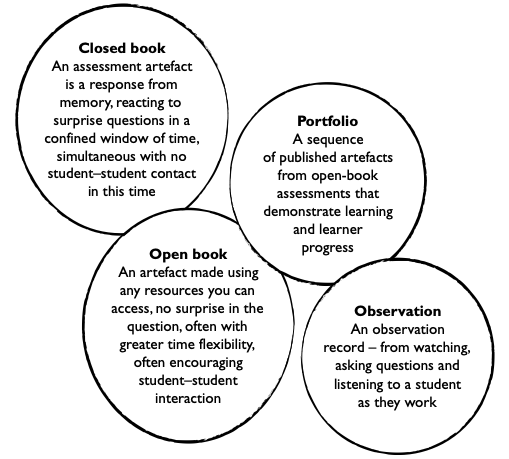

You can assess standards using traditional closed-book methods, though the kinds of questions you ask will be quite different. However, open-book and portfolio assessment is also very well suited to a standards-based approach. Observation assessments watch, listen to and strategically question students as they work. They include checklists and queries as a student reads aloud (Clay 2000; 2005).

See Clay on Observation Surveys.

The shift in underlying assumptions about the purposes of tests is enormous, even though it is easy to question the appropriateness of the assessments themselves. One of the best-known and most controversial attempts at educational reform in the early 21st century was the 2001 ‘No Child Left Behind’ law in the United States. Very similar things have happened in many other countries, so it is worth examining No Child Left Behind as a case study of standards-based assessment in practice. The ideas behind the law are credited to the Republican President at the time, George W. Bush. However, equally involved in its design was veteran and esteemed Democratic Senator Edward Kennedy, brother of President John F. Kennedy.

See McGuinn on the Origins of No Child Left Behind.

Critics of the law say that it has produced an education system dominated by testing. Schools and teachers are measured by end-of-year test results, on which basis they are rewarded with funding for their success or punished with the closure of failing schools. They have to meet ‘average yearly progress’ benchmarks and demonstrate that each year they are producing better test outcomes for their learners. The pressure this creates means that teachers feel compelled to teach to the tests, narrowing the curriculum to just those things the tests measure, such as mathematics and reading, at the expense of other areas of focus, such as the arts or writing (and writing is more expensive to assess than reading because it needs to be hand scored). It also means that schools tend to focus less on students who are likely to improve their results enough to cross threshold scores in order to focus on those who can be dragged across this line by the time of the test. In poor communities, schools are struggling to make progress through no fault of the teachers, given the stubborn link that appears in the results between poverty and lower scores. In effect, the school is blamed, and often the result is school closure or conversion to a ‘charter’ or semi-privatised school.

Even though much of the time the law seems to have dragged us back into the past of draconian tests and behaviourist punishments and rewards, it is built on a basic assumption, captured in its title, that every child can learn, every child can progress. Taking its rhetoric at its word, it does not accept that all students will be spread across a norm-referenced bell curve based on natural ability or that there are irreducible differences in intelligence between individuals and social groups. Every child can, and in justice should, achieve a criterion-referenced standard. And there are no differences in intelligence that mean that a student in the compulsory years of schooling cannot reach this standard. This is why the (today, very few) proponents of intelligence testing, oppose the law (Phelps 2009).

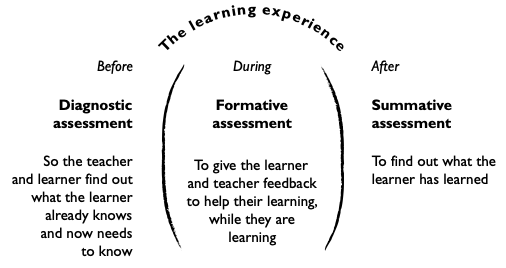

One of the main criticisms of testing regimes such as No Child Left Behind is that they focus on at-the-end, educational managerialism. That is, resources and energy are directed towards success in the prescribed test above all else. They do this at the expense of other, more effective diagnostic assessment to determine learner’s needs accurately, or ongoing and helpful-to-learners formative assessment.

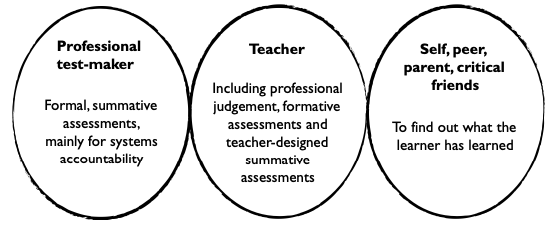

Finally, these kinds of assessment separate out ‘real’ prescribed assessments as the domain of experts who design and mark the tests and who, to manipulate the results, use statistical methods that are inaccessible and mostly unintelligible to teachers. Testing companies make a fortune providing their services to education systems. This is often to the neglect of other very powerful and useful forms of assessment, including assessments by teachers based on their professional judgement. It also neglects other, very valid assessment perspectives, such as assessments by self, peers, parents and critical friends. Such assessments could provide valuable, more timely feedback to learners at the point of need, and even useful measurement data.

How, then, does one distinguish a good test from a bad test, no matter what kind of test it is? The field of educational assessment identifies two standards for determining the effectiveness of an assessment:

• Validity – or whether an assessment is relevant to what the students have been supposed to learn and is thus an accurate measure of their learning. For instance, is the test a valid measure of the content of a stretch of curriculum as it was actually taught? A test about rivers should not have questions about mountains if they are not relevant to the understanding of rivers. Nor should it leave out any major areas of understanding about rivers identified and taught in the curriculum. Or – a vexing validity question – does a test that purports to test ‘intelligence’ or even disciplinary skills, actually test learned literacy skills or underlying cultural assumptions?

• Reliability – or whether the test (the river test, let’s say) consistently produces the same results, such as an identical test given at two different times or slightly different versions of the same test about the same thing that has been taught. Of course, reliability is hard to tie down if students happen to learn something from the first test or there are even some subtle differences between the two versions of the test or what was taught. And another example, a supply response test will be more reliable when different raters are given clear scoring rubrics linked directly to what has been taught, which help generate more consistent scores from rater to rater.

Dimension 2: Evaluation

Evaluation is a process that is used to judge the merit of an educational process or intervention. Examples of evaluations might include an evaluation of the current Year 8 History program in order to identify areas for improvement in curriculum design, a single-teacher effectiveness evaluation, an evaluation of the outcomes of a teacher professional development program, an evaluation of test results in relation to teacher and financial resource allocation, or evaluation of school-community relationships. Evaluations can occur in the planning phases of a program (for example, a needs evaluation), during a program to provide feedback that might suggest adjustments, or at the end of a program in order to decide whether to continue in the same way, or whether to change the direction of the program. Credible evaluations need to be mindful of, and grounded in, complex social ecologies marked by human institutions and their cultural practices.

The logic of evaluation involves:

• Purposes–What is being evaluated, and why should it be evaluated? Who are the stakeholders and what are their interests in the evaluation (for example, institutionally located authorities, such as outside funding bodies; people who are responsible for the operation of the program; intended beneficiaries of the program; or people who are systematically neglected or excluded by the program)? What standards of judgement are appropriate?

• Means–How is the evaluation to be conducted? What kinds of found and constructed data might be adequate to a valid and reliable evaluation? Found evidence may involve examination of plans and records, observations and attendance at regular meetings. Constructed data may include interviews, focus groups, surveys or formal assessments. Data might be analysed using quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods. Evaluation roles and perspectives may be internal

or external to the program, or a combination, and may include any one or more of self-evaluation, interested stakeholder evaluation or independent expert evaluation.

• Judgement–What does the evaluation mean? Is it culturally relevant and, if so, for whom? Evaluations require a particular kind of reasoning, linking context (human and instructional cultures) and purposes (an evaluation agenda) with means (collecting relevant evidence) to a judgement that has practical implications for the ongoing life of a program or intervention. Should the program continue and, if so, what recommendations for improvement might the evaluation offer? The measures of the value of an evaluation judgement will be whether its recommendations are useful in terms of its cultural context, original purposes, whether the evaluation methods produce an accurate and balanced basis for judgement, and whether the recommendations are feasible or culturally relevant.

However, rather like authentic pedagogy, no matter how thorough this process, and no matter how true to an educational situation, evaluation does not necessarily pro- duce the educational transformations needed in these times of disruptive change. The point of reference may be no more than the educational system as it is currently delivered, and how to deliver it better – how to get better test scores, for instance, when the whole assessment system is flawed, or how to meet externally-imposed managerial objectives when these are anachronistic or serve narrow interests. Or they may neglect the all-important contextual analysis of how to meet the everyday life needs of students for safety, dignity, engagement and personal expression within and beyond a learning ecosystem. Evaluations can, of course, play an important part in a process of changing the system, incrementally or in significant ways – but often they don’t. In fact, they can be used to reinforce the rules of the system even though they need changing, when, for instance, the most important change questions have been deliberately left out of the terms of reference of the evaluation.

See Schwandt on Defining Evaluation.

Dimension 3: Research

Research has a larger frame of reference than evaluation. If the focus of evaluation is a pragmatic utility – to work out how well education programs have done in their own terms, and beyond, in order to improve them – research aims to develop systematic, rigorous knowledge about learning in its institutional and social context. Of course, there are many close connections between research, evaluation and assessment. Research may produce institutional change, but that will only be an indirect effect of the knowledge it creates, rather than the primary purpose of the exercise. Research questions may be sparked by evaluations and assessments, or use evaluation and assessment data. Evaluations may also use carefully designed research methods as part of their task to find and analyse evidence. And research may use learner assessments as part of its research strategy.

Research takes two principal forms, both of which emerged in the 20th century:

• Quantitative research – The ‘gold standard’ for quantitative research is called ‘randomised controlled experimentation’ and it is regarded by some as the most scientific. This involves a ‘treatment’ group (students or teachers, for instance) who are given a ‘dosage’ of a particular intervention. Meanwhile, a ‘control’ group consisting of the same kinds of people are not given the intervention. They might just be continuing with their ‘business as usual’; an equivalent traditional program, for instance. One key rule of this quantitative research approach is that the number of research subjects must be large enough to be statistically significant. And a second rule, to avoid bias, the subjects (such as teachers or individual students) must be randomly selected using a kind of a lottery to determine who is in the intervention and who is in the control group. And a third rule, to avoid ‘contamination’, the two groups should be kept separate for the duration of the research, for instance, so the control group does not pick up any of the new ideas in the intervention or become influenced by them.

See In Defence of Quantitative Research.

• Qualitative research – This takes smaller groups, or even individual cases, and explores a question from as many varied perspectives as possible. The methods of qualitative research include case study research, which seeks to corroborate different perspectives on a case; single case research, which investigates in depth a learner or a class; ethnographic research, which builds a detailed description of the human dynamics of a learning community; and storytelling, in which the dynamics of a learning community are told in richly narrative terms. The techniques used in qualitative research include interviews, focus groups and on-site observation.

See Stake, in Defense of Qualitative Research.

As research is increasingly used to deepen and extend our educational knowledge, the advocates of one side or the other in this debate have descended into the ‘methods wars’. The proponents of quantitative research say that their methods are the only way to true ‘science’, using that word in the narrowest of its possible meanings. They believe that qualitative methods are too open to subjective ideological agendas to produce results that are dependable. Qualitative research samples, they claim, are too small and context-dependent to be able to produce knowledge that is usefully generalisable to other settings.

On the opposing side, the supporters of qualitative approaches criticise quantitative researchers for asking narrow questions that often do little to change educational paradigms. (Does this work or does it not work rather than how might we reconceptualise our ideas of what should work?) They also say that quantitative research can demonstrate results but not explain the specific dynamics that produce the results they have detected. Quantitative methods are also expensive, slow and not practically useable by teachers. They are expected to rely on expert academic researchers who use impenetrable statistical methodologies.

Every now and then a truce is called in the methods wars. Intermediaries in the debate advocate ‘mixed methods’, where complementary quantitative and qualitative perspectives are brought to bear on a question (Greene and Hall 2010).