Testing intelligence and memory: The modern past

Dimension 1: Assessment

From its beginnings in the nineteenth century, student testing has been an important aspect of modern, mass, institutionalised education. Textbooks often have tests at the end of each chapter. Some textbook publishers even publish separate tests to go with their books. The teacher might end a week of mathematics with a test. Or they might have frequent tests or quizzes to check that their students have learned their spelling words. Or the students might write a paragraph or an essay on a topic that they hand in for marking. This is how teachers keep an eye on their student’s learning, as well as providing them feedback on how well they are doing.

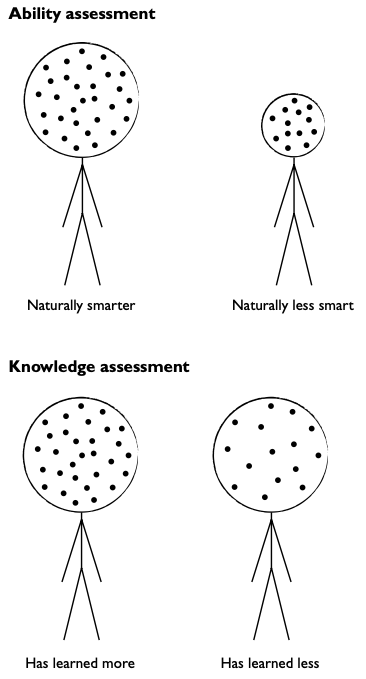

Then, there were what we call today ‘high-stakes’ tests (Nichols and Berliner 2007). Intelligence tests, discussed in Chapter 6, were used to divide groups of students into different groups of learners, classified by their supposed natural ‘ability’. A high IQ result might mean you would go into Class 3A, but a low IQ score would consign you to Class 3D, where you would be given work appropriate to your ability, and perceived social destiny. Except for specialist uses in the case of students with disabilities, intelligence tests have been thoroughly discredited, and with them the idea that some individuals might not be able to learn very much so we should not try, or the idea that different performance at school has something to do with intelligence and that therefore we should resign ourselves to limited success with some students. Also, the idea that groups perform differently based on their natural capacities (racial, ethnic, or gendered or social class groups, for instance), has been almost universally dismissed as prejudicial and dangerous (Fischer et al. 1996; Ceci 1996). This is one of the huge changes in education since the era of didactic teaching, when the idea of natural intelligence was prevalent.

See Gould on the Mismeasure of Man.

The other main kind of assessment purpose has been to measure knowledge, as distinct from ability. That is what you could remember in response to the prompts provided by the tests. At the end of a curriculum or program of learning, a formal, externally set examination would determine your graduation results and the possibilities for entry into further levels of education.

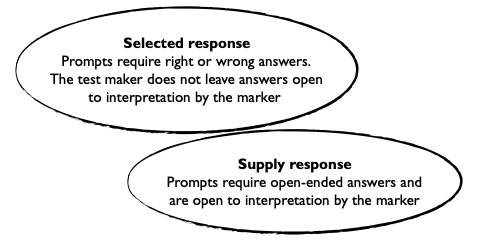

Two main kinds of assessment emerged in the twentieth century, both of which are alive and well today: selected response assessment and supply response assessment. Selected response assessment is where a student finds the right answer among wrong ones. Supply response assessment is where the student provides an open-ended response.

Here is a sample selected response question: ‘The French Revolution occurred in A. 1879, B. 1789, C. 1787, D. 1877.’ Of course, you would need to ask quite a few questions like this before you, as an assessor, could be sure the student had thoroughly learned their history of the French Revolution.

And here’s a supply response question: ‘Discuss the causes of the French Revolution’. In this case, just one question is enough to elicit an essay response from the student, which will demonstrate whether they understand the topic at hand.

Both kinds of test were almost invariably what was called ‘closed book’. The student had to respond with no resources at their disposal other than what they had managed to remember.

See Popham on the Types of Test

Selected response assessments require the test taker to choose from among the alternatives offered, including, for instance, true/false, ABCD alternatives and matching words. Only one response can be correct. The other responses are not only wrong, they are designed to trick you into thinking that they could be right. These alternatives are called ‘distractors’ (Haladyna 2004). It would be easy to think the French Revolution happened in 1879, because although the answer is a nearly a century wrong, it’s a transposition of the numbers in the correct answer. Or if you knew that it happened in the late eighteenth century, but were not sure of the exact year, 1787 is just two years off the right answer. This is how distractors work: they are answers that are deceptively nearly right. But they are still as wrong as any answer to this kind of question could be. You get zero marks even though you were so close to being right.

The easy simplicity of selected response tests is that they offer a standard score, with a consistent path to interpretation of the student’s answer. If a student gets 23 out of 25 questions right on their French Revolution test, we can call that 92%. But the student who only has 15 questions right gets 60%, a passable but not great result. The advantage of selected response assessments is that they can be standardised. If exactly the same test is administered to the same group of students in the same way, and their results vary, then the creators of these tests conclude that this must say something about the students’ differential abilities (intelligence tests) or knowledge (tests of curriculum content).

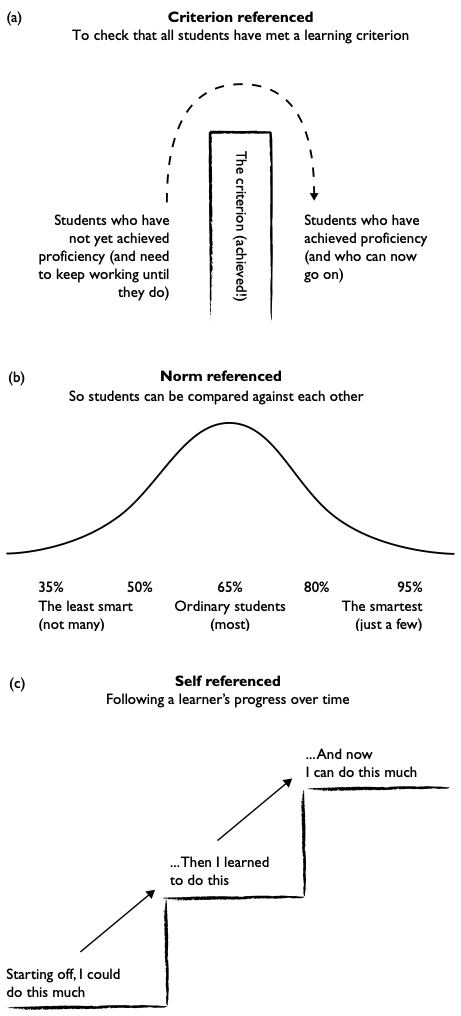

The process of comparing students is called ‘norm referencing’. Ideally, a test pitched at just the right level will spread the students’ results neatly across a normal distribution curve, in the shape of a ‘bell curve’, with a few poorly performing students getting a very low score (30s to 50s, say), a few high-performing students getting a very high score (80s and 90s, say), but most students getting a middling score (60s and 70s, say). In this way, the score for each student compares their ability or knowledge to other students who are at the same level and have completed the same curriculum.

Selected response tests require a particular form of interpretation of results. They do not directly test the student’s actual understanding of the French Revolution, or mathematics, or whatever. These are complicated, multifaceted ideas grounded in whole disciplinary practices, or ways of seeing and thinking about the world. This is what we really want to measure: historical and mathematical understanding. But to get a rough idea of the student’s complex capacities to think and their mastery of an underlying body of knowledge, selected response assessments ask questions about a sample of separate knowledge points in the student’s understanding. Each of these knowledge points has to have a clear-cut correct or incorrect response. The score is the basis for an inference about the student’s understanding.

Sometimes, however, these inferences may be flawed. Consider the example of a multiple-choice mathematics problem where the correct answer is C. 42 (not A. 40, B. 402 or D. 4.2). A student may have selected the correct answer but used a seriously flawed method and way of thinking to arrive at that result. Another student may have answered 4.2. While their answer is incorrect, due to having overlooked a small miscalculation in their workings, they may have fully understood the mathematical concept. You would only be able to see this by looking at the student’s workings and explanations of their workings. However, a selected response test can only produce an inference about student understanding based on straightforwardly right and wrong answers. This inference may be flawed.

In selected response tests it is also hard to ask questions requiring deeper understanding and interpretation. In a reading comprehension, it is possible to give a correct answer to a question such as ‘On which day did the action happen? A. Wednesday, B. Thursday, etc.’ however, it is not possible to require a correct response to the question, ‘Do you think the main character exhibited A. heroism, B. cowardice, C. opportunism or D. pragmatism?’ This is because the latter question is open to interpretation depending on the perspective of the reader. In fact, this is an important question to be asking from the point of view of literary understanding, and certainly more important than the mundane and probably irrelevant question of which day of the week. However, ‘which day?’ is the kind of question that will end up on the test because it produces a correct or incorrect answer. The problem is that this kind of a question is peripheral to the intellectual task of relating to a literary reading text. It is so peripheral, in fact, that the student would probably have forgotten that detail by they time they have finished reading and have to scan back over the text, looking for isolated words – the days of the week.

Selected response tests can only ask about facts, rules and definitions that can be isolated as separate atoms of knowledge and can be correct in a clear-cut way. They leave out other aspects of knowledge, and often the most important ones. They are also a kind of game or puzzle, and a peculiar one at that. Selected response tests are quite different from actual historical exploration and knowledge, actual mathematical calculation and understanding, or actual reading of literature and interpretation of its deepest meanings. Here’s a way to play the game, or to unravel its puzzle: first eliminate the options that you know are wrong; then, when you get to the final two alternatives, try to figure out the carefully placed trap in the second last answer. Or if you don’t have a clue, just guess because at least you have a chance of getting the right answer, and if you do, you’ll get the same credit for that question as someone who really knows (Sacks 1999).

See Davidson, A Short History of Standardised Tests.

Today, selected response tests are still alive and well. For good reasons as well as bad, since about the closing decade of the twentieth century, we have become obsessed about educational measurement. The positive reasons are so we have better information about learners so we can teach them better. The negative reasons are the implicit and often not-so-implicit threats to teachers and schools who do not perform on these straightforward numerical measures. If the test scores are poor, it must because the teachers are bad or the schools are not providing good value for public money.

There is also a practical reason for the continued popularity of selected response tests: they are cheap to deliver in a standardised, mass production mode. With computerised scoring – pencil marks on paper or answering the questions directly on a computer or tablet – large numbers of students can take tests and the scores are added up automatically. Mind you, the testing companies charge a fortune for this, but nevertheless it is a way to get the same test to thousands of students without the huge number of hours that would be required for human scoring.

See Garrison on the Origins of Standardised Testing.

However popular today, selected response tests can have the effect of narrowing our intellectual horizons. They were invented in a world in which the production line was divided into small steps. They assume we can do the same with knowledge. However, this is a world where information and ideas are joined up, and the most important topics of investigation are controversial, without neat right and wrong answers (the environment, diversity, social change and the like).

See Kortez on What Educational Testing Tells Us.

Supply response assessments, by comparison, allow for full and sophisticated responses from students. But they require a huge amount of human effort to mark, and the scores are open to variation depending on the different interpretations of markers. This can be reduced by providing clear rubrics, with specific success criteria and levels of performance on each criterion. To ensure the fairness that is essential in a high-stakes tests, moderation is required, using multiple markers to ensure ‘inter-rater’ reliability. For instance, another rater or a super-rater takes a sample of scripts, scores them again to see whether the first rater’s scores should be moderated because they are generally too hard or too easy in their overall assessment.

Supply response assessments can be norm referenced (giving scores that rank students against each other) or criterion referenced (for instance, to say whether a student ‘has achieved proficiency’ in a certain skill). Norm referencing compares students in respect to the differences in their performance. Criterion referencing could produce the ideal result that every student in the group has ‘achieved proficiency’ or should keep working at something until they do. Both selected and supply response assessments can also be self-referenced, tracking a learner’s progress over a series of comparable tests, over time.

Despite these differences between selected response and supply response assessment, in the frame of reference of didactic pedagogy both kinds of assessment test memory. They do not directly test a student’s capacity to see the world and interact with the world in a way that a mathematician or historian does, which involves accessing and assembling findable cognitive resources. Instead, they test what the student has remembered. This might be short-term memory in the case of the comprehension question about Wednesday – so short term, in fact, that by the end of the text you have forgotten this was mentioned in the first paragraph, so when you reach the question, you have to go looking for the day of the week. Or it might be longer term memory, hoping you manage to remember that the relevant year was 1789 so you can appear historically competent when, in the closed-book examination for the end-of-year modern history course, you write your essay response to the question about the causes and effects of the French Revolution. How long such memory actually lasts is the butt of jokes about cramming for exams and the stuff forgotten the next day, or the trivia that amazingly you have managed to remember all these years later, notwithstanding their practical irrelevance. Tests that rely on memory out of context are of questionable value for learning and learners.

Many assessments today remain within this memory-dependent frame of reference. And this, notwithstanding the fact that practical knowledge today consists of things you look up, sources you can rely upon and expert specialists you rely upon as needed, because you can’t hope to know everything relevant to your life and work. Knowledge is what you can do rather than what you can remember. The two, of course, are linked in powerful ways. But today, there is much that we can discover on a need-to-know basis as we search the web or use the apps on our phones – it would be a waste of time to try to commit to memory many of the things we used to learn this way. The same is the case in workplaces today – given the complexity of knowledge and its changing nature, to get a task done we rely on the differential knowledge and experience of others in teams and the wider organisation, so that the intelligence of our working group comes out of our collaborative interactions. The messages of the social-cognitive approach to learning that we described in Chapter 6 are more relevant than ever: the skills of seeking knowledge as needed, collaborating, abstracting, and discerning patterns while navigating through large bodies of knowledge.

Dimension 2: Evaluation

In earlier modern times, there was not much educational evaluation. Schools were regarded as properly authoritarian places where you would faithfully learn what you were taught. The test scores spoke for themselves, and these results reflected more on the learners than the teachers and the school. Every few years, an inspector might come into a school. Their interests were of an elementary, managerial kind: order, respect for hierarchy, compliance to rules and using appropriate textbooks. After schooling was made compulsory in most places in the world from the 19th or 20th century, school inspectors would check whether the school was keeping adequate attendance records, pursuing truants and prosecuting their parents. They would check that buildings were safe and well maintained. They might even go into classrooms to check teachers’ records.

Dimension 3: Research

Nor, before the second half of the twentieth century, was there much educational research. John Dewey in the United States and Maria Montessori in Italy were early educational researchers. Their agenda was to experiment with alternatives to the didactic pedagogy of their time, rather than to use the research to examine its effects and improve its effectiveness. Both believed that they needed to find other pathways to success for those who were failing traditional education. Intelligence tests were also developed as part of the early research programs of the new field of psychology, led by people such as Thorndike, Yerkes and Goddard, discussed in Chapter 6. They too wanted to understand, and make explicit, the factors that contributed to success or failure in education. Their work supported the prevailing view that it was the abilities of students, not the quality of schooling, that determined learning outcomes.