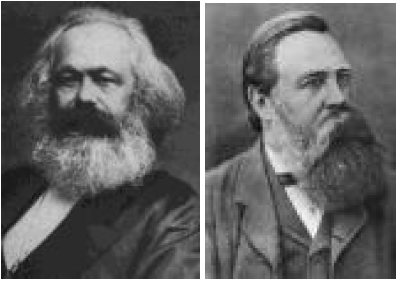

Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels on Industrial Capitalism

Karl Marx (1818–83) was born in Germany into an assimilated Jewish family. As a brilliant young university student, he trained in philosophy and was greatly influenced by the thinking of the German philosopher, Hegel, who had developed a philosophy of history. He met Frederick Engels (1820–95), son of a wealthy industrialist, in Paris in 1844 and they became lifelong friends and intellectual partners. During the revolutions which swept Europe in 1848, they prepared the Communist Manifesto, an analysis of the emergence of industrial capitalism, a program for its overthrow and a plan for its replacement by a communist society in which the workers owned all enterprises and took over the reins of government. During the 20th century, these ideas became the basis for communist revolutions and states from Russia to Cuba.

Marx and Engels were early critics of the effects of the modern factory system, predicting its end as the workers rose up and took control of a system which exploited them so badly and treated them as appendages to machines.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels describe the emergence of a new industrial society and the unequal relationships between its different social classes. This inequality, they believed, would breed hostility between two most important classes, the ruling or bourgeois class, which owned the ‘means of production’, and the working class or proletarians, who were worked to the bone to create the wealth of the bourgeoisie.

[T]he modern working class … [is] a class of labourers, who live only so long as they find work … These labourers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market.

Owing to the extensive use of machinery and to division of labour, the work of proletarians has lost all individual character, and, consequently, all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him …

Modern industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalist. Masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, are organised like soldiers. As privates in the industrial army they are placed under the command of the perfect hierarchy of officers and sargeants … They are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine, by the overseer, and, above all, by the individual bourgeois manufacturer himself. The more openly this despotism proclaims gain to be its end and aim, the more petty, the more hateful and more embittering it is …

But with the development of industry the proletariat not only increases in number; it becomes concentrated in greater masses, its strength grows, and it feels its strength more … The unceasing improvement of machinery, every more rapidly developing, makes their livelihood more and more precarious … Thereupon the workers begin to form combinations (trade unions) against the bourgeois; they club together in order to keep up the rate of wages; they found permanent associations in order to make provision beforehand for these occasional revolts …

Now and then the workers are victorious, but only for a time. The real fruit of their battles lies, not in the immediate result, but in the ever expanding union of the workers. This union is helped by the improved means of communication that are created by modern industry, and that place workers of different localities in contact with one another. It was just this contact which was needed to centralise the numerous local struggles, all of the same character, into one national struggle between classes … [This will then turn into a] more or less veiled civil war, raging within existing society, up to the point where that war breaks out into open revolution …

[T]he Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things … Let the ruling classes tremble at a communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.

WORKING MEN OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE!

Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1848 (1973). ‘Manifesto of the Communist Party.’ Pp. 62–98 in Karl Marx, Political Writings: The Revolutions of 1848, edited by David Fernback. Harmondsworth UK: Penguin. pp. 73–74, 75–76, 78, 98. || Amazon || WorldCat