Post-Fordism: More recent times

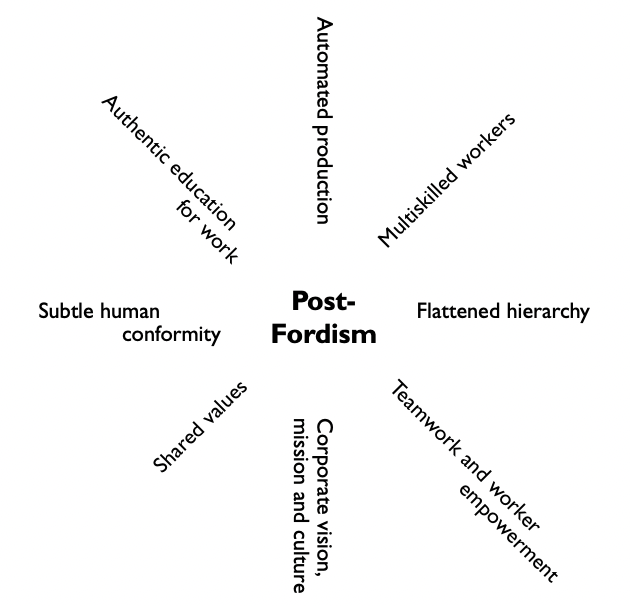

In times of bewildering change, diversity and uncertainty, we can easily find ourselves stumped for words to adequately describe what we are experiencing. So, social scientists have invented a number of ‘post’ terms – ‘post-industrial’, ‘postmodern’ and ‘post-colonial’ – to describe aspects of our contemporary societies. In the same vein, ‘post-Fordism’ describes a form of work organisation that is in many important respects quite different from Fordism. Post-Fordism tries to respond to many of the inherent problems and deficiencies of Fordism.

The gradual and uneven shift into working conditions that might be labelled post-Fordism demands from education different skill sets and dispositions. These and other social changes throw into question the premises and ongoing relevance of didactic teaching. Less than any explicit edicts, a general sense of the changing times has gradually shaped a different kind of education to supply a changed workplace with a new kind of person.

Dimension 1: Technology

Toyotashi, outside Nagoya in Japan, is one of the archetypical sites of post-Fordist work. Throughout its relentlessly urban and industrial landscape are scattered a number of large Toyota plants. In Plant No. 5, we stand watching the production line roll past, making cars at a pace and with a smooth efficiency that, were he here with us, would surely have inspired even that harsh task master, Henry Ford.

However, speed and efficiency is where the resemblance ends. Instead of mass production, the logic of production is now one of differentiation. Every other car on the production line is not just a different colour, it is also a different model. A computerised inventory system passes the windshield to the robot, which gently places it into the correct vehicle on the line. However, around these simple motions – just as simple as the motions of the worker making Ford’s Model T – is a deep shift in technological process and organisational logic (Cope and Kalantzis 1997).

The technological feel of Toyota’s Toyotashi Plant No. 5 is one of lightness and adaptability. Cybernetic information systems guide the robots and the inventory system. These information systems are based on the notion of self-monitoring ‘feedback loops’. Data is constantly circulating, the information system watching and checking, evaluating and predicting, what has just been done and what needs to be done next. The production process is open to continual software readjustment. It is based on principles of responsiveness and flexibility. Just-in-time inventory demands accurate communication of information and rapid responsiveness on the part of suppliers.

See From Assembly Line to Just-in-Time.

Production-line workers now need high levels of skill to be able to deal with the complexities of the technology. The workers on the factory floor all belong to teams, constantly interacting with each other and the information systems, interacting as a group, reading the information low and taking responsibility by intervening when necessary. These technological and human relationships are often also called ‘flexible specialisation’ (Piore and Sabel 1984).

See After Fordism: Piore and Sabel on Flexible Specialisation.

Dimension 2: Management

The Toyota Company was founded in 1937. Amid the chaos of postwar Japan, in 1949 the company faced a series of crippling strikes and nearly collapsed. That year, Eiji Toyoda, an engineer and nephew of the founder, visited Ford’s Rouge Plant in the United States. He decided that American-style mass production was not for Japan. Toyota had never been a mass manufacturer. Total production in the twelve years since Toyota was founded was 2685, compared with an output of 7000 per day at Rouge. Japan had a small domestic market. There was a shortage of capital. There were no immigrants available who might work in substandard conditions.

This is how Japan’s ‘lean production’ system came into being. Compared with mass production, the new Toyota system was based on smaller batches, less capital, shorter product development time, smaller inventories and, instead of vertical integration where all the divisions of the enterprise came within the control of one company, ‘just-in-time’ sub-contractual relationships with independent suppliers – meaning that the supplier was always there, ready to supply the component immediately it was ordered.

A degree of worker control was also ceded in the Toyota plant. Strong unions were given an official role in the running of the organisation. Teams were assigned responsibilities, including power to stop the line. An approach to problem solving was established, which involved every person so that problems once resolved never happened again. A suggestion scheme elicited workers’ ideas. And a ‘total quality management’ system showed up mistakes instantly or, better still, prevented them from happening before they needed to be rectified. Beyond the organisation, a closer relationship was established with car dealers, so that production of specific models could be finely tailored to meet demand (Womack, Jones, and Roos 1990).

Eiji Toyoda’s measures reflect an important moment in the history of work and management in the 20th century. In the last part of that century, this new production system was established in many parts of the world. By the 1980s, even the United States was keen to copy the lessons of Japan’s extraordinary postwar economic success story. This is how the authoritarian, Fordist, top-down management system came to be replaced in many workplaces by an approach that involves teamwork, and worker empowerment and responsibility.

At the smallest group level in the organisation, workers are organised into self-managing teams in a working culture based on ‘shared values’. Team leaders are typically selected on the basis of interpersonal skills as well as technical capabilities, including their sensitivity to every team member’s needs and capacities, and their ability to support team members so they could give of their best. The leader is meant to be a mentor or teacher more than an authority figure.

This devolution of decision-making and control to self-managing teams is some- times called ‘flattened hierarchy’. If teams can make decisions for themselves, so the argument goes, why do we need all those layers of middle management to make decisions for them? Indeed, the workers often understand their jobs better than their bosses and so have the capacity to make better-informed decisions, to the benefit of the whole enterprise.

Throughout the enterprise, the machine-like command structures of Fordism are replaced in the post-Fordist workplace by the guiding metaphor of organisational ‘culture’. Work is like a community. Ideally, the workers identify with the ‘mission and vision’ of the organisation. They internalise its ‘organisational values’. They are able to act autonomously and responsibly on behalf of the organisation because they have an intuitive feel for it. They develop an intrinsic interest in its success.

Or, at least, that’s how the post-Fordist theory goes, as told in countless training sessions, meetings, retreats and business-planning workshops. Workers may wish to question the extent to which the story rings true, or the extent to which their status is elevated within the company culture.

However, one overarching generalisation can be made: the post-Fordist organisation reflects a shift in the balance of agency in the workplace. Teamwork shifts the site of some decisions about production from senior management to shop-floor team leaders and team members, integrating workers into the enterprise decision-making processes. If workplaces are sites of governance and consent, post-Fordism changes the organisational politics of work. The autarchy of Fordism is replaced by the guided democracy of post-Fordism. The ‘empowered’ worker is supposed to take on the vision and mission of the organisation, belonging to its culture, wholeheartedly taking part in its teams and sharing its values. Systems-structure-command talk is replaced by motivation-culture-responsibility talk.

See Peters and Waterman, ‘In Search of Excellence’

Dimension 3: Workers’ education and skills

Ford had reduced the skill level required of every worker to a bare minimum, based on the principle of the division of labour into smaller and smaller components. In the post-Fordist workplace, however, more of the unskilled jobs are taken over by machines as part of the process of increasing automation of production. This means that fewer unskilled workers are needed than before. Society also needs fewer process workers. There is a sense of fear that jobs are being taken by machines. Where, then, will the new jobs be? The answer to this question comes in part in the rise of service and ‘knowledge’ industries that create new areas of employment. Even in the traditional manufacturing and agricultural sectors of the economy, the skill levels required in order to operate sophisticated machinery have risen steadily, reversing the trend towards de-skilling, which was a characteristic feature of Fordism.

Post-Fordist ‘multi-skilling’ becomes the order of the day. Contrary to the de-skilling characteristic of Fordist production processes, workers in the post-Fordist enterprise need to be able to undertake a broader range of complex tasks. They need to be flexible enough to shift from one task to another at different times during the production process – a form of work that became known as ‘multi-tasking’. Technologies, moreover, are shifting more rapidly than ever. The broader and deeper your skills and knowledge base, the more readily you will be able to adapt in an environment of constant change.

The most immediate and direct impact of this change on education is felt as employers and governments recognise the need for a more highly skilled workforce. They turn to their education systems to meet this demand. Since the middle of the 20th century, the numbers of people going on to higher levels of technical and professional education have increased markedly. In fact, the proportion of the population in the education system at any one time has grown more rapidly than total social investment in that system. Hence, the squeeze on resources that is so often felt in education, despite its growing (and acknowledged) significance in the development of a more highly skilled workforce (McMahon 2002).

The change from a Fordist to post-Fordist form of work organisation is not just about increased levels of technical work skill. The post-Fordist workplace calls for different dispositions – workers who can act autonomously and responsibly, who can troubleshoot and come up with creative solutions, who do not feel like they know the answers but have the resources to find things out and who can work effectively as team members. What kind of education will best serve this post-Fordist workplace? Didactic teaching may have produced the ‘right’ kind of person for the Fordist workplace, but this kind of person is not necessarily well suited to the new work order of flexible specialisation.

Authentic education starts ‘where the student is at’ and ‘builds motivation’; it facilitates individualised or student-centred ‘inquiry’; and it encourages ‘discovery’ learning and ‘problem solving’. In these respects, authentic education promotes classroom practices that are better aligned to the subjectivities suited to the post-Fordist workplace.

See Dewey on Education for Active Workers.

The historical connections between the rise of post-Fordist work and authentic education may be messy and complex. Teachers did not come to work one day to find instructions to create a new kind of person for the new regime of post-Fordist work. History rarely works in such obvious ways, with such clear relations of cause and effect. It is enough simply to note the compatibility of post-Fordist work and authentic education, and a broad parallelism on their development paths. The two are fellow travellers in a slow and uneven process of social change.

Dimension 4: Markets and society

The shift towards post-Fordist forms of work has been accompanied by some enormous social transformations. What motivates people to go to work and what is supposed to make them ‘tick’ at work has changed enormously. An economy of person-to-person command has been replaced by an economy of self-motivation. But this works only so long as the workers’ goals align with those of the bosses. Hence, the corporate emphasis on training in teamwork, to develop a corporate culture, instil the organisation’s vision and inculcate its mission.

Even though its forms of organisation and work processes are different from those of a ‘Fordist’ enterprise, the post-Fordist enterprise is still a place of relative cultural uniformity. This uniformity, however, is now based on pressures rather than commands to conform – to it into the team and share its values, to express belief in the organisation’s mission and to ‘clone’ to its corporate culture. This is a softer form of assimilation than Fordism. However, if you don’t it in, you find yourself hitting a ‘glass ceiling’ rather than being thrown out onto the street.

In the realm of consumption, too, although there’s an appearance of wider choice, this is often only superficially the case. The car you go out to buy might be any colour or style, but underneath there’s not that much product choice, let alone the choice not to consume. If you don’t live near public transport you still need a car and there’s no escaping the wage–consumption cycle. Meanwhile, despite the seemingly egalitarian talk of teams and cultures, workers rarely do better than get only slightly more affluent, and then if they are lucky, while bosses get very much richer. Relative inequality grows.

Fordism also remains comfortably alongside post-Fordism in a relationship of uneven development. As developed countries move towards ‘new economy’ workplaces, the sweatshops and the dirtiest of industrial production are shifted to poorer regions within a country or to the developing world. It seems, at times, that post-Ford- ism in one place needs Fordism in another. This symbiotic relationship means exclusion from the more advanced post-Fordist forms of work and consumption around enduring and systemic divisions between the developed world and the developing world; the rust belt and the sun belt; higher-paid workers and lower-paid workers; and those who can afford to consume in fancy niche markets and those who can only afford generic, mass-produced goods.

See Richard Sennett on the new ‘flexibility’ at work.

Post-Fordism’s limitations are also authentic education’s limitations. Workers are more in control of what they do at work; but the agenda is set by the internalising objectives of the boss and assimilation to the cultural feel of the organisation. Learners are more in control of their learning; but what is being learned is still the one right answer from the academic discipline, or content that is ‘relevant’ to your supposedly inevitable social destiny.