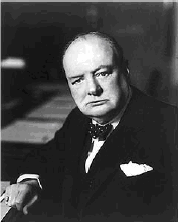

Winston Churchill’s School Days

At the age of seven, Winston Churchill (1874–1965)—later to become Prime Minister of Britain during the Second World War—was sent to St. James’s preparatory school where flogging ‘was a feature of the curriculum’ and kindness and sympathy ‘conspicuously lacking’—as he was later to write in his autobiography, ‘My Early Life’. Churchill’s father was a member of the English aristocracy and his mother an American heiress. Before entering politics, he had a military career, seeing active service in defending the British Empire in India and Sudan. He also spent a brief time as a journalist in South Africa during the Boer War. Churchill attributes his entrance the military to his father’s noticing his childhood love of toy soldiers and the perception that he was a poor student. In fact, Churchill is remembered for his brilliant ability as a speaker and his moving speeches that unified the British public in the ‘darkest hours’ of the Second World War. In his famous speech to the British Parliament, he said, ‘We shall fight on the beaches. We shall fight on the landing grounds. We shall fight in the fields, and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender!’ Here he describes his school days in ‘My Early Life’:

Churchill relates a story about the discursive game his Latin teacher played:

‘This is a Latin grammar.’ [The teacher] opened [the textbook] at a well-thumbed page. ‘You must learn this,’ he said, pointing to a number of words in a frame of lines …

What on earth did it mean? Where was the sense of it? It seemed absolute rigmarole to me. However, there was one thing I could always do: I could learn it by heart …

‘Have you learnt it?’ he asked.

‘I think I can say it, sir,’ I replied; and I gabbled it off.

He seemed so satisfied with this that I was emboldened to ask a question …

‘But,’ I repeated, ‘what does it mean?’

‘Mensa means a table,’ he answered.

‘Then why does mensa also mean O table,’ I enquired, ‘and what does O table mean?’ …

“O table,—you would use that in addressing a table, in invoking a table.’

‘But I never do,’ I blurted out in honest amazement.

‘If you are impertinent, you will be punished, and punished, let me tell you, very severely,’ was his conclusive rejoinder.

Such was my introduction to the classics from which, I have been told, many of our cleverest men have derived so much solace and profit …

How I hated this school, and what a life of anxiety I lived there for more than two years … I counted the days and the hours to the end of every term, when I should return home from this hateful servitude … My teachers saw me at once backward and precocious, reading books beyond my years and yet at the bottom of the Form … Where my reason, imagination or interest were not engaged, I would not or I could not learn. In all the twelve years I was at school no one ever succeeded in making me write a Latin verse or learn any Greek …

[By] being so long in the lowest form I gained an immense advantage over the cleverer boys. They all went on to learn Latin and Greek and splendid things like that. But I was taught English. We were considered such dunces that we could learn only English. Mr. Somervell—a delightful man, to whom my debt is great—was charged with the duty of teaching the stupidest boys the most disregarded thing—namely, to write mere English … Thus I got into my bones the essential structure of the ordinary British sentence—which is a noble thing. And when in years my schoolfellows who had won prizes and distinction for writing such beautiful Latin poetry and pithy Greek epigrams had to come down again to common English, to earn their living or earn their way, I did not feel myself at any disadvantage.

Churchill, Winston. 1960 (1930). My Early Life. London: Oldhams. pp. 17–18, 19, 23. || Amazon || WorldCat