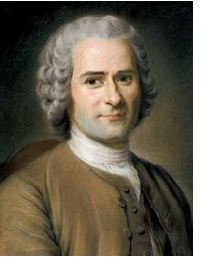

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–88), one of the most influential modern political and social philosophers, is best known for his idea of the social contract or the agreement people make to live together in community. This is an arrangement which in practice institutes inequality. However, if the contract is rethought and reinstituted, as Rousseau suggests, it is also potentially the basis for a more equal society. Rousseau’s conception of equality did not, however, extend to gender equality. Rousseau also wrote on the subject education, in a book which described the fictitious education of a boy called Emile. An extract describing how Rousseau’s would educate Emile is to be found in Chapter 7. The following, however, is Rousseau’s ideal for the education of Emile’s imaginary wife, Sophy, in which Rousseau argues that women should receive a different kind of education than men.

All the faculties common to both sexes are not equally shared between them, but taken as a whole they are fairly divided. Woman is worth more as a woman and less as a man; when she makes a good use of her own rights, she has the best of it; when she tries to usurp our rights she is our inferior …

To cultivate masculine virtues in women and to neglect their own is evidently to do them injury … Women are far too clear sighted to be thus deceived; when they try to usurp our privileges they do not abandon their own; with this result: they are unable to make use of two incompatible things, so they fall below their own level as women, instead of rising to the level of man. If you are a sensible mother you will take my advice. Do not try to make your daughter a good man in defiance of nature …

Does this mean that she must be brought up in ignorance and kept to house work only? … No, indeed, that is not the teaching of nature, who has given woman such a pleasant, easy wit … nature means them to think, to will, to love, to cultivate their minds as well as their persons; [nature] puts these weapons in their hands to make up for their lack of strength and to enable them to direct the strength of men. They should learn many things, but only such things as are suitable.

When I consider the special purpose of woman, when I observe her inclinations or reckon up her duties, everything combines to indicate the mode of education she requires. Men and women are made for each other, but their mutual dependence differs in degree … Hence her education must, in this respect, be different from man’s education.

The children’s health depends in the first place on the mother’s and the early education of man is also in a woman’s hands; his morals, his passions, his tastes, his pleasures his happiness itself, depend on her. A woman’s education must therefore be planned in relation to man …

Boys and girls have many games in common, and this is as it should be … They have also special taste of their own. Boys want movement and noise; drums, toy-carts; girls prefer things which appeal to the eye, and can be used for dressing up-mirrors, jewellery, finery, and specially dolls. The doll is the girl’s special plaything; this shows her instinctive bent towards her life’s work. The art of pleasing finds it physical basis in personal adornment, and this physical side of art is the only one which the child can cultivate … We have here a very early and clearly-marked bent; you have only to follow it and train it … Little girls always dislike learning to read and write, but they are always ready to learn to sew.

Do not be afraid to educate your women as women; teach them a woman’s business, that they be modest, that they may know how to manage their house and look after their family …

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1762 (1914). Emile, or Education. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. pp. 321, 327–328, 330–331, 336. || Amazon || WorldCat