From exclusion to assimilation: The modern past

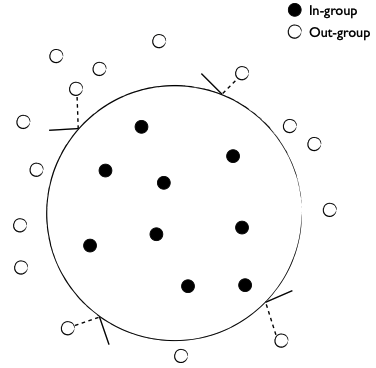

Exclusion and assimilation have been and still are two ways of dealing with lifeworld differences, whether practised by countries, communities, organisations or schools. Both are premised on the idea that the members of a group need to be more or less the same for that group to function well. However, in some important respects, the exclusionist and assimilationist ways of achieving the goal of sameness, are also quite different.

Exclusion or separatism is a process by means of which a dominant social group maintains its sameness by refusing to allow in people who are different in defined ways. The segregating school, for instance, does not allow students to attend who are of the ‘wrong’ race. The single-sex school does not allow in students who are of the other sex. The wealthy school – circumstantially, even when not as a matter of principle – excludes students whose families can’t afford to pay the fees or live in its neighbourhood. Often, these practices are seen to be discriminatory. In some circum- stances, they are made illegal.

Sometimes, however, separatist institutions may be a justifiable way to manage lifeworld differences. Some say that schools designed for specific ethnic or minority communities help learners because they support their languages, cultures and values. They offer students an affirming environment that helps them succeed – unlike mainstream schools, where their cultures and languages are marginalised. Others say that schools for girls only give them a chance to succeed without being distracted by, or having to compete with, boys. Clearly, also, separatism works for wealthy schools because it means that learners come to school with the cultural capital of families habituated to social influence and mainstream success. This ‘good’ social standing turns into strategically valuable networks with other wealthy and powerful families.

The assimilating social group is just as concerned as the separatist one to make a virtue of homogeneous community, but it does not use the same methods. This group says something like, ‘We will accept people who are different, so long as they become like us.’ The assimilating school, for instance, makes little allowance for the lifeworld differences amongst its learners. It simply immerses everyone in the singular culture and curriculum of the school. If that’s what’s good for anybody, then that’s what everybody is going to get. Whether you feel comfortable or alienated in this environment, or whether you succeed or fail, is up to you, the learner. You may choose to rise to the ‘values’ and ‘standards’ of the school and if you don’t, you are likely to fail – and then have nobody to blame but yourself.

Sometimes, this approach may be justified, and it may even work. For some learners, it may serve as a kind of crash-course in a new culture: ways of speaking, kinds of thinking and types of people. It may open doors that would never have been opened had they stayed within the comfortable boundaries of their lifeworld origins.

What, then, are bases of separatism or assimilation? What are the differences, real and perceived? Lifeworld differences are complex, overlapping and come across as a spectrum of many hues and shades. Notwithstanding the subtleties, we need categories to describe the differences. For clarity’s sake, we group differences into three clusters: material, corporeal and symbolic.

Dimension 1: Material conditions

Social class

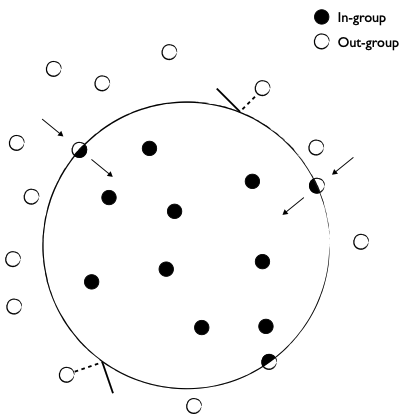

Social class is a material or economic measure of wealth, power and status in an unequal and hierarchically ordered social structure. In their historical form before conquest, most first nations or indigenous peoples lived in classless societies. They had other means of social differentiation and hierarchy, for sure, such as age and gender, but they did not have the material difference of social class that has marked the rest of human history (Sahlins 1972). In slave societies (such as ancient Greece and Rome, and also more recently in the southern United States until the Civil War of the 1860s) an underclass of workers was bought and owned and sold by masters (P. Anderson 1974b). In the pre-modern, peasant–agricultural societies of Asia, Europe, Africa and some parts of the Americas, feudal lords owned the farming land and peasant vassals gave part of what they produced to the lord in the form of tithes, or a kind of rent (P. Anderson 1974a). In each case, the wealth of the few was created by the work of the many. At the time, most people considered this to be inevitable and proper.

Modern capitalist societies create class and inequality in a different way from their predecessors. The key is the modern money economy and the system of paid employment. Unlike slavery and feudalism, people in capitalist societies are free to take any job offered to them by an employer. And they can leave their job any time they wish. But they are hardly free not to work in the wage labour system. The elderly, the disabled and stay-at-home parents may be dependent on a wage earner or receive welfare payments from the state. However, welfare recipients only provide for minimal support. This keeps them near the bottom of the class system. It also makes even low-paying and unpleasant work often more attractive than not working. In reality, there is little choice for most people but to work for most of their adult lives, at least if they want to enjoy what is considered to be an acceptable standard of living.

People in paid employment may work hard, but some people’s return on their work remains less than others. If you are an owner or a shareholder in a business, you earn more than what you would if you were a worker in that business, without necessarily working any harder than the worker. In fact, as the 19th-century philosopher and political economist Karl Marx pointed out, business owners do well because their workers work hard. They do well because they collect the surplus or profits generated by the hard work of the workers (Marx and Engels 1848). The system works this way for them because they were born wealthy or are able progressively to accumulate the capital and property that enables them to control and profit from other people’s labour.

The most obvious sign or measure of social class is wealth in the form of assets (property, shares, accumulated cash) and the income that comes from these assets. If you don’t have assets or your assets are few, you have no alternative but to work for a salary or wage. Marx argued that the unequal ownership of social assets creates a self-perpetuating system in which the rich will always get richer and the poor will get poorer.

The German sociologist Max Weber added two more measures of class: power and status (Weber 1922). Power refers to the degree of control you have over your own life and the lives of others. If you are a wealthy factory owner or a manager you have much more control over the way you work than do the workers on the factory floor. You give orders rather than take orders. You hire and fire. Economic power also brings with it social power beyond the organisation, including the capacity to influence civil society and the state.

Status refers to the prestige attached to a person’s position in society. Social status can be achieved – for example, through education and associated well-paying work – or ascribed through inherited wealth and social standing. Class and social status are embodied in everyday cultural practices and the visible trappings of affluence. People of power and status tend to have tastes, cultural interests and styles that require considerable material resources to maintain. They exhibit a set of behaviours and demeanours that are regarded as ‘having class’. Such people can afford to buy art to put on the walls of their houses, purchase tickets to the opera, go on holidays to beautiful and interesting places, play golf at the most expensive clubs, drink the best wine, send their children to the best private schools and pay their fees to attend the most prestigious universities.

Occasionally, someone from a lower class makes good and, when they do, the status aspect of class immediately sticks out. ‘How crass’, old money says of new money, or the ‘nouveau riche’, when they wear gaudy jewellery or drive tastelessly flashy cars.

Where do schools sit in relation to social class in times and places where differences lead to either exclusion or assimilation? In an exclusionary system – even when education was provided by the state for all its citizens – schools in working-class neighbourhoods mostly have poorer facilities and larger class sizes. They lack the resources to provide extra-curricular activities that might compensate for the paucity of available community or family resources. Poorer students tend to be offered basic literacy and numeracy training rather than a broader curriculum. If they are moderately lucky, they are steered into ‘vocational’ courses that have them leaving school to join trades. Meanwhile, private schools and well-endowed public schools in affluent neighbourhoods may have facilities and expectations that are oriented to higher education and extend and deepen networks of power and influence for the ruling class. The more affluent get a better education because they can afford it. More resources are put into their education. Greater results are expected, and delivered. This is how, in an institutional sense, education creates a system of exclusion based on social class (Bowles and Gintis 1976).

A milder version of this process of social selection is to assimilate ‘bright’ working-class students into the status system. If you do well at school, if you perform in terms measured by its academic subjects and forms of behaviour, you too may succeed in getting a paid job that may even take you beyond the class station of your parents. In reality, however, social mobility or assimilation to a new social class only happens in the case of exceptionally motivated students, such as the children of immigrant parents, doggedly determined that their offspring should improve their lot in life.

By and large, however, even assimilationist systems reproduce social class position across generations. The reasons are material, cultural and institutional. If you do not grow up in a household full of books and newspapers and where people read a lot, if your family speaks a language or dialect different from the ‘standard form’ of language used in the curriculum, if your family’s way of talking and thinking about the world is contextual and narrative rather than abstract and conceptual – to name just a few of the possible gaps between school and home – school often seems to present insurmountable challenges (B. Bernstein 1971). And when you fail, when you don’t manage to assimilate to its culture, the system tells you – or, even more conveniently for the system, you can tell yourself – that you only have yourself to blame. You were not smart enough to succeed even though school gave you the opportunity.

See Bowles and Gintis on Schooling in the United States.

Locale

Locale is another aspect of material difference. Different geographical locations offer different opportunities: the various neighbourhoods in a city; rural or remote versus urban location; different regions in a country; being in a developed or developing country. Locale is a determinant of the quality and depth of material and cultural resources available – education, health, libraries, parks, museums, media access and the like.

Migration is one way to change locale, be that a short distance from the country to the city, or a journey around the world. Many migrants move because they are seeking improved work opportunities, or better schooling and thus social opportunities for their children. However, strict limits are imposed on the lows of migration by receiving countries. Even if one does get the opportunity to migrate, establishing roots in the new locale may be experienced as a process of assimilation, or changing oneself – one’s language and culture, for instance – in order to it in.

Family

Family circumstances also contribute to the material conditions of everyday life. In an earlier modernity, the ideal and typical form of family was the nuclear family – mother, father and a few children. Father worked, earning a wage sufficient to support his ‘dependents’. Mother did unpaid domestic labour at home. Increasingly, however, more women worked to earn additional cash income for the family. Other types of family were frowned upon in an earlier modernity or practically hard to manage. Extended families, such as those of immigrant or indigenous groups, were not easy to maintain because the physical forms of housing and dispersed work opportunities made them difficult to sustain. Single-parent families were usually the result of the death of a parent, or what was regarded to be the immorality of extramarital sex (and unmarried mothers were encouraged to adopt out their children) or the then-stigmatised and relatively rare phenomenon of divorce. Serial monogamy was frowned upon because marriage was meant to be for life. Parallel sexual relationships were clandestine and condemned as adulterous. De facto marriages were rare. Blended families in which siblings had parents from different marriages were regarded as anomalous and dysfunctional. Polygamy, as practised by some fundamentalist Christian and Muslim groups, was so remote from public consciousness as to be almost unimaginable. Same-sex marriages and parenting were unheard of.

The realities of family life were always more complex than the nuclear ideal. The differences, however, were handled through processes of social exclusion and cultural assimilation. Persistent pressure was applied to conform to the symbolic norm. Children from families not conforming to the norm could at times suffer in public contexts; for example, when they were taunted at school. They could also be disadvantaged by the peculiar culture of their family life – whether the national language or the language of instruction was spoken at home, or whether they had access to resources in the home (toys, books or trips that gave them a wider experience of the world), or whether their family could provide the cultural capital at home (the ways of thinking, the ways of speaking and the aspirations and expectations) that meshed with the culture of the school and its curriculum.

See What Sissy Juppe Didn’t Know about Horses.

Dimension 2: Corporeal attributes

Corporeal or bodily differences have both a physical aspect (the actualities of a per- son’s body) and a cultural aspect (the symbolic meanings ascribed by a person to their own body, or ascribed by others).

Age

Age is a determinant of bodily and mental capacities, and relevant and appropriate forms of learning.

From birth to about the age of two or three, babies are completely dependent on parents and carers. At birth, humans do not have a clear sense of the relations of their bodies to the environment around them, or even a capacity to see objects clearly. In the first months of life, their main activities are simple and reflexive, such as sucking, touching and grasping. Gradually, these develop into more complex, volitional activities: rattling a toy or looking for a hidden object, knowing that it may exist even when it is not visible. The baby comes to understand that there is a distinction between their body and the world outside of their body. Over these years, everything the baby learns is by means of immersion in a context of informal learning. This is how they learn to see, to walk and to talk. By the end of two years, the baby will have acquired a system for representing the world to themself – using language and other symbols (Stern 1985).

From the age of two or three to about five, children develop fine motor skills, begin to relate to their peers in a social context, and learn to express themselves through symbolic processes of communication. Egocentric speech, or talking to oneself in a kind of monologue, reflects a way of thinking about and understanding the world. The child may believe that the natural world has been made by people and that the whole world shares their feelings, desires and perceptions. For example, when covering their eyes, the child believes nobody can see them. Nor is the child able to make a distinction between symbol and symbolised, or word and thing. In terms of visual representations, children start representing meaning in this period without making a distinction between writing and drawing, and gradually separate the two modes as they begin in the formal educational setting of early childhood education (Vygotsky 1934).

From about age six to 12 years, children in modern societies attend primary or elementary school. Fine motor skills are reined. Cognitive capacities progressively grow and develop. Children acquire a capacity to classify and order, coming to the realisation that something with the same properties may appear in different manifestations. These are the beginnings of logical thought processes, problem solving and the capacity to create and apply abstract concepts – generalising thoughts that cross varied sites and instances, and naming these thoughts with concepts. They also develop a capacity to see something from another person’s perspective and to realise that their own perspectives are just that, not necessarily the final truth (Piaget 1929). Same-sex friendships predominate, with some children (particularly girls) reaching puberty or adolescence towards the end of this period.

From ages 12 to 17 years, most young people are in secondary school, and in a transitionary period as they move from child to adult behaviour and take on greater social responsibility. They find themselves in an ambivalent and contradictory middle-ground of dependence, with growing expectations of maturity. Adding to the pressure is puberty and the development of adult sexuality. Peer group pressures arise – the need to belong, and to form an identity that accords with that sense of belonging. Cognitively, young people in this age bracket develop capacities for formal logic (such as induction and deduction), to conceive abstractly, to evaluate interests and perspectives critically, and to act in ways that have a wider impact on the world and take responsibility for these actions.

See Piaget’s Stages of Child Development.

Between about 15 and 21 years, young adults go through a number of rites of passage that eventually mark them as adults. They leave school; they vote; they get a driver’s licence; they can purchase alcohol or cigarettes. From then until about age 40, they typically go through a period of early adulthood in which they may complete their education (such as vocational or higher education), start work and begin family life.

From about 40 to 60 years, these adults continue to work, now freer of responsibilities for children. Formal learning may continue through adulthood, but when it does, its sites and dynamics are quite different from child learning.

From about age 60, people may begin to retire from full-time work, independently at first and, as they get older and more dependent, in increasingly supported, quasi-medical environments.

These age transitions are characteristic of modernity. In earlier societies, more people were involved in taking care of young children than a stay-at-home mother or a childcare specialist. Learning was in a social context that involved many adults, rather than in a specialised institution – the childcare centre and after that the school – designed exclusively to look after children. Children had to make more adult-like contributions and to make them earlier. In fact, the culture of childhood in its current form (from its toys to its patterns of dependency) is a relatively recent invention.

From about the nineteenth century, for the first time in human history modern societies began on a wide scale to make a number of clear distinctions of age that locate people of different ages in institutions specially designed for that age group at that particular stage in their life-course. Formal educational institutions clearly make these age separations. Babies are typically the responsibility of non-working mothers in the nuclear family, or crèches. Three- to five-year-olds are frequently sent to early childhood education settings or preschool. By the age of five, almost all children are sent to kindergarten. Six- to 12-year-olds go to primary or elementary school, or middle school. Thirteen- to 17-year-olds go to secondary or high school. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child defines childhood as a period lasting until the age of 18 (“United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child,” n.d.).

Race

‘Race’ refers to phenotypical differences, or differences in physical appearance, between one human population and another: skin colour, facial features, hair col- our and texture, height and physique. The roots of the word in English are to be found in old Italian and French words for breed or lineage, where the term was initially used to describe subspecies right across the natural world. The modern obsession with classification led 19th- and early 20th-century scientists to divide humans into distinct racial groups, such as ‘Negroid’, ‘Australoid’, ‘Caucasoid’ and ‘Mongoloid’.

Neat categorisation like this is regarded with suspicion today, and ‘race’ has become a controversial term (Miles 1989). Biologists and anthropologists dispute how useful the term is to describe groups of humans. Racial grouping is based on certain kinds of genetic difference, which may appear obvious but do not reflect many important underlying genetic differences. Indeed, on most biological measures of difference, there is greater inherited biological variation within populations (such as blood types and range of heights and body shapes) than the average variation between populations.

Among those who wish to use race as a biological category, there has been considerable controversy about how many races there are, and where one race begins and the next ends. Indeed, one of the factors that confounds the concept of race is the extraordinary range of global movement of the species and the extent of inter-breeding over the quite brief span of existence of modern humans as a species (Cavalli-Sforza 2000; Sykes 2001). No human populations have been separated for more than a few thousand generations – not long enough for significant biological variations to emerge through processes of natural selection. In fact, if one considers one’s biological ancestry as two intersecting pyramids, one at which you are at the peak of the pyramid (with two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents) and another where an ancestral ‘Eve’ was a member of a tiny population from which the species emerged (who had however many children, and grandchildren and great-grandchildren), the human family is so closely related over the few thousand generations of its existence that nobody today can be further removed than 50th cousin (Shoumatoff 1985).

Even though race is not a particularly helpful biological category, the recognisable differences it describes have figured large in our social imaginations. These differences have been associated with different states and stages of civilisation and progress, with different human capacities and with different levels of acquired intelligence. They have been used to justify imperialism as the ‘white man’s burden’ to bring the coloured races to a higher level of civilisation. They have been used to rationalise the unequal results of schooling – if black people do not do well at school as a statistically measurable population, it must be the result of innate intelligence, so the argument goes, and this means that the problem cannot be solved by changing educational or social conditions (Eysenck 1971; Herrnstein and Murray 1995; Fraser 1995).

In these senses, ‘race’ is very real. It is a historical and cultural construction that has real effects. Indeed, it often becomes the basis for an interpretative framework or worldview that is today called ‘racism’. Racism is an ideology that ascribes causal social, cultural and historical significance to biological differences between groups. It can be explicit in the form of pejorative or negative statements, or implicit in world- views and social structures that have the effect of reproducing patterns of exclusion and inequality for populations marked by their visible difference.

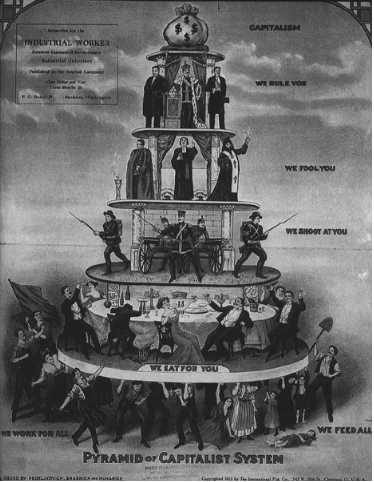

In modern times, racist ideology has been used to justify exclusionary practices. Apartheid created separate homelands for black people in South Africa (Gilmore, Soudien, and Donald 1999). Slavery in the United States before the Civil War created a class of people marked by their skin colour who could be bought and sold as property. After the Civil War, segregation institutionalised the second-class citizenship of former slaves (J. Anderson 1988). The Indigenous peoples of Australia were isolated on mission settlements in the initial phases of the colonisation of the Indigenous peoples of Australia. Before that, the ‘black line’ set out to eliminate the Indigenous Tasmanians (Reynolds 1995). These are examples of the most extreme forms of racist exclusion, which in the twentieth century included the Armenian Genocide of 1915, the Nazi project to exterminate the Jewish ‘race’ in Europe between 1933 and 1945 and the Rwandan Genocide of 1994.

Sometimes, also, assimilationist race agendas have been practised, such as the removal of Australian Indigenous children of ‘half-caste’ parentage from their families, who were placed in white foster families on the assumption that it was possible to ‘breed out’ their Indigenous characteristics – that their racial characteristics would progressively disappear as future generations intermarried with white people (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission 1999).

Sex and sexuality

Sex is the biologically inherited difference between females and males. In the animal kingdom, creatures of the female sex typically produce the larger of the two reproductive cells. The smaller cell is contributed by the male. The female also bears offspring. In humans, females have two X chromosomes; a reproductive system consisting of a vagina, clitoris, uterus and fallopian tubes; a predominance of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone; and, after puberty, a menstrual cycle, breasts, a smaller physique than men and a distinctive overall body shape. Males have one X and one Y chromosome; a reproductive system consisting of a penis and testes; a predominance of the hormone testosterone; and, after puberty, facial and body hair, a lowered voice, a larger physique than women, less fat than women and a distinctive body shape. Girls reach puberty several years before boys, and women’s reproductive capacities end before men’s, at menopause (Suggs and Miracle 1999).

There are behavioural differences between men and women, too, but it is hard to determine the extent to which they may be the result of biological inheritance (sex) or cultural acquisition (gender). The wide variation in human propensities and social attributes within each sex, across and between different societies, suggests that cultural factors outweigh or can override biological factors.

Until recently, modern societies were reluctant to take sex differences into account beyond the simple female–male dichotomy. For instance, when a person had a combination of male and female sexual organs, this seemed to require a one-way-or-the-other approach in which one sex was ascribed (Dreger 1999).

The bipolarity of earlier modern gender roles also excluded permutations of sexuality that have become more public in recent times. In the past, heterosexuality was considered the norm and continues to be considered so in many communities today, based on the premise that female–male attraction and partnering is natural. People who felt they did not it the prevailing gender mould found they had no alternative but to lead ‘normal’ lives, repressing their sexual orientation or practising their sexuality in secluded places – having to hide homosexual or bisexual inclinations, ‘in the closet’ (Sedgwick 1985).

Physical and mental abilities

What is it to be tall or short? What is it to be ‘fat’ or ‘thin’? What is it to have physical characteristics that may be conventionally classified as ‘beauty’ or ‘ugliness’? And what is it to have a ‘disability’ of some form or another? All of these bodily attributes powerfully frame identity. One aspect of the framing is cultural ascription, in which a person’s identity is developed in relation to prevailing views of what is ‘normal’ or ideal. Another aspect is physical, or what a person’s body, including their brain, can or cannot do.

In earlier modern times, views of the ‘normal’ or ideal were more clearly defined than they are today. People whose bodily or mental capacities were too far removed from the norm of the able-bodied and mentally it were frequently labelled in categories that had, or came to have, pejorative connotations. Such people were labelled as ‘crippled’, ‘lame’, ‘spastic’, ‘deaf’, ‘dumb’, ‘blind’, ‘insane’, ‘mad’, ‘feeble-minded’, an ‘idiot’ or a ‘moron’. Clear institutional separations were established. Bodily and mentally ‘subnormal’ people were not expected to go to ‘normal’ schools or work in regular workplaces. They were confined to home if a full-time carer was available. Or they were sent to special institutions – schools for the blind, deaf and disabled, asylums for the insane and ‘sheltered workshops’ for the physically disabled (Bowe 1978).

Dimension 3: Symbolic differences

Symbolic differences arise from the human propensity to make meaning. Humans make sense of their encounters with the world in creatively varied ways.

Culture

Uniquely in the natural world, humans are symbol-making creatures (Deacon 1997). They have the capacity to envision the world, and use these visions to drive their actions to refashion the world. Making symbols is at the heart of culture. Humans are cultural beings by nature. On this definition, all symbolic activities could be called ‘culture’, including language, gender, affinity and persona. For the moment, however, we define culture more narrowly, as nationality, ethnicity or ancestry.

The modern world is geopolitically divided into nations. Nationalism is an ideology and a set of political and cultural practices that attempts to create more-or-less homogeneous peoples to it within the boundaries of nation-states, or the geographical territories covered by state sovereignty. Typically, the most powerful cultural group stamps its cultural mark onto national identity. Its language or dialect becomes official. Its own story becomes everyone’s story. Its members benefit by gaining privileged access to political power, material resources and symbolic kudos.

The term ‘ethnic group’ typically refers to minorities, although the distinctive attributes of majority national cultures could just as easily be called ‘ethnic’ (Glazer and Moynihan 1975). It suits majorities to regard their culture as the norm and other people’s cultures as exotic or different. Sometimes, ethnic groups are historical minorities: people who may have lived in a place for a long time alongside today’s majority group but who have found themselves to be in the minority at some point in the past when the borders of the modern nation were drawn or redrawn. Other times, ethnic minority groups have formed as a result of migration.

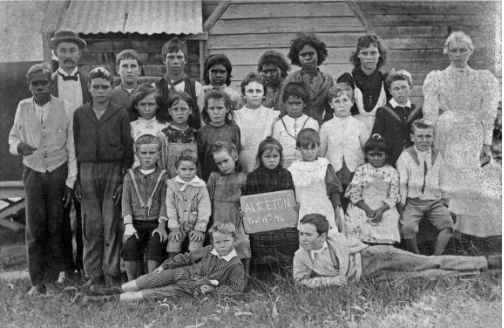

Indigenous peoples, or first nations, are not usually considered to be ethnic groups because of their unique historical status as original landowners and their social position in the modern nation-state (Nakata 2001). Indigenous peoples have typically become minorities at some point in the past, when imperial conquest and migration of new settlers brought an end to their exclusive sovereignty over native lands. On this basis they make justifiable claims to ongoing ownership of wild lands and compensation for their loss of lands now inhabited by settler communities and their descendants. They also tend to have had vastly different ways of life from the invaders and new settlers, and suffer severe social dislocation and enduring injustice as a consequence of the encounter.

The modern nation-state has two approaches to ethnic groups and indigenous peoples. One is exclusion or separatism – to ban immigration of certain groups, or to remove indigenous peoples to reserves and homelands without the right to citizenship in the nation.

The other approach is to insist on their assimilation. A condition of joining the nation is that the ethnic or indigenous group must take on the cultural attributes of the dominant group – learn to speak its language and imbibe its values. If there are to be any traces of ethnic or indigenous identity, these have to be confined to the home or to private life.

See A Missionary School for the Huaorani of Ecuador.

Language

Modernity brings with it decreasing language diversity. Of the world’s approximately 6000 ancestral languages, many have disappeared over the past half-millennium, and the majority of those that remain are threatened by the dominance of the major imperial languages in the most powerful domains of knowledge, society and economy (Phillipson 1992; Kalantzis and Cope 2012b).

The story of language diversity tells of innumerable differences of dialect (the accent, word choices or manner of speaking of a particular group), register (a variety of language used in a particular setting, such as in an informal, formal or professional setting), social language (a mode of communicating within a particular group, such as the social language of football or computing) and discourse (language peculiar to a domain of activity) (Gee 1996).

Modern societies privilege certain dialects, registers, social languages and dis- courses. Some of these are more or less powerful in the public realm. Some carry more or less powerful forms of knowledge. Some bear the symbolic burden of representing more or less marginalised cultural and social groups.

In schools, children may be disadvantaged when they don’t speak the language of instruction as their mother tongue. Or, given the enormous significance accorded to written language in modern societies, children may be disadvantaged if they come from speech communities that don’t provide substantial access to, and afford significant value to, books and writing. Typically, those who are disadvantaged are speakers of minority immigrant or indigenous languages, who speak the national language as a second language, or those who are poor and who speak in a working-class register that is more distant from the language of writing than middle or upper-class speech.

See William Labov on African-American English Vernacular.

One possible ‘solution’ to this problem is to advocate assimilation, to learn the language of the mainstream in order to succeed. Whether this can work, or is even seriously meant to work much of the time, is a matter of contention.

Gender

Connected to the biology of sex, gender roles are socio-cultural, or symbolic. They are the result mostly of processes of informal learning or socialisation. Babies, whose only manifest differences are biological, style themselves as boys and girls, prefiguring the archetypical adult roles assumed by men and women. Girls amuse themselves with dolls, dress daintily and play house. Women become homemakers or join professions of caring and nurturing, such as nursing, teaching or secretarial work. Boys interact with toy vehicles and weapons, and play rougher sports than girls. Men become workers who venture out into the robust public worlds of the professions and trades. From the moment a baby develops a human consciousness, pervasive cues and influences prompt them to develop subtly and deeply gendered habits, interests, demeanours, stances and dispositions. It becomes hard to disentangle what is learned or socialised and what is sex-related biological inheritance.

In an earlier modernity, gender-role differentiation seemed to be more straight- forward than it often appears today. Learning typical or ‘normal’ gender roles was such a pervasive and subtle ‘fact’ of the lifeworld that these differences appeared to be natural (de Beauvoir 1952; Mitchell 1971). To the extent that gender roles were more clearly defined in an earlier modernity and continue to be defined in traditional ways today, girls and women feel emotions more keenly and are more able to express affection. They are more sensitive to social and interpersonal realities. Boys and men tend to dominate in social settings and act more aggressively more often. They are more likely to take risks. Their actions are based more on instrumental or means-ends rationality. And they have a closer relationship to machines and technology than do girls and women. These kinds of attributes become the stuff of feminine and masculine personae, behaviours, dispositions and social aspirations.

See Jean-Jacques Rousseau on Sophy’s Education.

In the past, the adult world of gender roles also took clearly differentiated structural and institutional forms. It was not until the 20th century that women could vote. Women would mostly join the workforce only if they were poor or until they were married or had children. Men, meantime, would build lifetime careers. Women’s jobs were paid less than men’s.

Schools were frequently gender-segregated, particularly secondary schools, teaching subjects appropriate to boys’ and girls’ social destinies – trade skills in boys’ schools and domestic science or home economics in girls’ schools, for instance. It was to be expected that an elite group of boys would go on to higher education in order to join one of the male professions. Girls might go on to train to be nurses or secretarial assistants. Teaching was primarily a low-status, female profession.

See Catharine Beecher on the Role of Women as Teachers.

Gender roles in the modern household came to be defined around the nuclear family with father working on the labour market, mother doing unpaid domestic work and looking after the two-point-however-many children that became the norm. Never before had the private realm of the home and women been so dramatically separated from the public realm. Women were placed in isolation with their immediate biological children, staying in separate household spaces, often undertaking their domestic work with scarce or no help from their husbands and with little or none of the community engagement with the wider world that their husbands experienced at work.

When the husband came home, he clearly asserted his dominance as head of the nuclear family. The often-authoritarian tone of the traditional nuclear family was not so unlike that found in the public realms of work and citizenship. Most husbands were expected to comply in these public spaces. When they came home, however, they became the head of the household, assuming an authoritarian position there. Wives and children were expected to take orders from them. Family life, in other words, was conducted through another one of those relationships of command and compliance typical of the times. The man, who had been compliant in his public persona, was transfigured into a command personality when he came home.

The cultural and institutional processes of exclusion in modern gender relations are called ‘sexism’. Sexism is an ideology and set of practices that ascribe natural- ness and inevitability to the gender-role differences that are associated with sex differences. Its effect is to justify and perpetuate the inequality of males and females. Sexism conveniently starts with the bodily realities of sex differences, and then naturalises the cultural practices of gender roles and their unequal outcomes. It is as though the inequalities are inevitable because they are natural. The effect is the exclusion of women from the public realm and from realms of power that are the traditional domain of men. However, when we separate the underlying bodily realities from the cultural construction of gender roles in the lifeworld, the inequalities that have historically been associated with gender roles are neither natural nor inevitable. There can be no biological justification for the patterns of exclusion.

See Mary Wollstonecraft on the Rights of Woman.

Sometimes gender roles seem so powerfully ingrained that the inequality they enshrine appears almost insurmountable. The only way for a woman to succeed in a man’s world, it seems, is to become like a man – to focus on her career at the expense of domesticity or to act like a man by taking risks and focusing on means-ends rationality. In other words, the only alternative to separatism is assimilation. If she is not to be excluded from the world dominated by masculine gender roles, a woman needs to assimilate to at least some of the attributes of the male gender role.

See Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex.

Alternative frameworks for sexuality beyond the bipolar male–female norm throw traditional gender roles into question. Sometimes homosexual men and women, for instance, take on aspects of male and female gender roles typical of their sex. Sometimes they don’t. However, homosexual people living outside the conventional male–female gender bipolarity of earlier modern times were pressured by processes of exclusion and assimilation to take on conventional gender roles. If they did not conform, they faced a prevailing culture of homophobia or fear and dislike of homosexuality.

Affinity and persona

You are who and what you associate yourself with. You are the person you envision and style yourself to be. Despite the pressures to homogeneity of earlier modernity, differences of affinity and persona have always abounded. There have always been variations in religious belief, from one major religion to another, from one denomination to another, and from people who believe there is a God or are gods, to agnostics who don’t know or care whether there is a god, and atheists who are clear in their own minds that there is no god. There are large differences in political viewpoint, expressed implicitly through a person’s ideological framing of the world, or explicitly through political advocacy or membership of a political organisation. There are enormous variations between the kinds of people who belong to different types of organisations (football team members compared to members of a golf club, for instance) or whose interests and enthusiasms are different, such as their hobbies or their preferred leisure activities. There are differences in peer culture within and between age groups. And there are different personality types, such as introverts or extroverts.

The way the earlier modernity dealt with these kinds of differences was to regard affinity or persona as an essentially private affair. What you think is your own business, and is better not expressed in public. ‘Never talk about religion or politics,’ the old adage goes. What you do with your free time is your own affair. This kind of difference, it was thought, was best kept at home rather than taken to work or school.