What’s ‘new’ about ‘New Learning’?

In part, this book describes education today: what goes on in schools, the role of the professional teacher, what it is like to work in a school as an organisation, the psychology of learners, the job of instructional design, how to manage a classroom and the assessment of learner outcomes. These are the practices of education today, built on the familiar foundations of our yesterdays.

However, we also want to consider a renewed mission for education in these ‘interesting times’. Huge changes are afoot, in the world outside the formal educational institutions and in the kinds of learners that ill those institutions. Perhaps at times the people who manage and staff the institutions of education do not feel a need to change. But often they do need to, whether they feel that need or not.

Hence, the idea of ‘New Learning’. In order to build a view of what’s happening in education today, we need a broader view of learning – of what people need to know and do in the contemporary world outside the walls of formal educational institutions, regardless of what their teachers might consider good for them in their usual teaching practices, and beyond what practitioners of the discipline of education might be in the habit of prescribing from their books of received wisdom. New Learning is located in that peculiar territory of anticipation, where a ‘might’ becomes a ‘can’, becomes a ‘should’, becomes a ‘will’, and maybe, all being well, eventually becomes an ‘is’.

Here are eight dimensions of learning today that may prompt us to formulate a theory and practice of New Learning.

Dimension 1: The social significance of education

When our political leaders use the rhetoric of the ‘new economy’ and ‘knowledge society’, they tell of a large and significant social transition. Knowledge is now a key factor of production: an economic and thus social fundamental. All the talk of the ‘knowledge economy’ moves education to the heart of the system, as a crucial part of the fabric of economic and social progress. This applies to individuals as much as it does to economic and political society – more than ever, education serves as an essential ingredient of personal ambition and success, even a key determinant of one’s earning capacity. It is also presented by political and community leaders as a mechanism for ensuring social equity, so the ‘have-nots’ get a chance to achieve the success that was previously limited to the ‘haves’.

See Walter McMahon on the Economics of Education.

Dimension 2: The institutional locations of learning

More and more learning is happening outside the traditional educational institutions – on the job, at play, through the media, on the World Wide Web. This produces a crisis of relevance for schools, colleges and universities. They have long been the sites of pedagogies that ‘teach about’ the wider ‘outside world’; for instance, through the sciences of the natural environment or the geographies of human communities. The school curriculum divides the world into subjects that take on the appearance of being self-sufficient, rather than the partial and specific views of the world that they are. And when this world is changing so rapidly, the disconnect between content and the world itself grows ever greater. This is not to say that educators should second- guess the specifics of the future to make their subjects more directly relevant – that is nearly impossible and, indeed, not the point. Rather, institutionalised education needs to become less of a site for ‘learning about’ bodies of content knowledge, and more a set of experiences of ‘learning in and for’ a world whose future shape we can- not predict. In order to become relevant once more, educational institutions should reappraise the traditional boundaries of discipline content; perhaps moving to teach through new modes and subject configurations, to recognise and accredit knowledge that has been acquired outside the program and classroom, and to take their teaching mission outside the comfort zones and habits of their institutions.

Dimension 3: The tools of learning

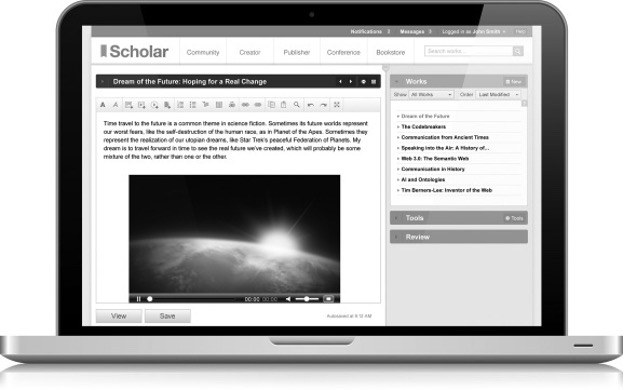

The new media that have transformed so much of our personal, community and working lives require a change in the tools of the teaching trade. In the past, education systems have been relatively slow to respond to the new media, let alone to lead the way in their development and the development of innovations in teaching and learning. Since the turn of the century there has been a flurry of activity around the role of information and communications technologies in schools, but not yet to the extent that the new media are being used to promote discernible changes in the mainstream schooling experience. Distance learning, learning at home and work, community integrated learning, learning with other learners who are not sitting in the same classroom – the new media allow us to blur the boundaries that neatly enclosed traditional classrooms and learning institutions. Among the new tools, the digital learning media loom large, presaging a change that could be as large and as revolutionary as the mass application of the classroom in earlier modern times – itself a learning architecture and communications technology.

See Kalantzis and Cope, New Tools for Learning: Working with Disruptive Change.

Dimension 4: The outcomes of learning

What kinds of capacity will the New Learning promote? Compared to the form of learning that is characteristic of our recent past, the New Learning is about learning by doing as well as learning by thinking: about the capacity to be productive in the world as well as knowing that world; about action as well as cognition. The older learning tended to be individualised and cognitive (with educational performance measured by the stuff in one’s head that gives one a competitive advantage, in exams, then jobs, then life). The New Learning adds the dimensions of practical capability and collaborative social learning so that thinking is also connected with an ability to act and to be adaptable, responsive and flexible in a world of diversity and change. One can be a resilient individual, but that resilience has to connect with the sophisticated sociability of collaborative learning, group work, emotional empathy and a holistic understanding of the global as well as local consequences of one’s actions. New Learning anticipates a different kind of learner.

Dimension 5: The balance of agency

The ‘balance of agency’ refers to the mix of teacher and learner subjectivities in the learning process. In the learning of the earlier modern past, teachers told and asked, and learners listened and answered. Syllabuses and textbooks presented the contents of the disciplines, which learners recounted in tests – getting it ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. The balance of agency was heavily skewed towards the knowledge authorities of teacher, curriculum designer and textbook writer. The teacher’s subjectivity was dominant; the learner’s was subservient. This seemed right for a world in which bosses were bossy, political and military heroes led, the mass media propagandised, we consumed mass-produced commodities that someone else supposed were good for us, cultural icons were revered and narratives were to be listened to and appreciated. It no longer seems so right in a world in which agency rather than obedience is becoming regarded as a key to economic and social achievement.

The New Learning affords a shift in the balance of agency in the same direction that is evident in the world at large. This is an evening-up of balance, so that learners are as much makers of their own knowledge as the receivers of it, and teachers are designers of learning activities as much as they are knowledge experts. In fact, what teachers do in the New Learning is to ‘design in’ a greater share of learner responsibility for learning. This helps to form the sorts of learner identities that will be more effective in a world in which workplaces use teamwork and a self-motivating work- place culture to get the best out of people, in which we need to take responsibility for our own level of civic participation, in which we can choose our own interpretations of the world from hundreds and thousands of media channels, in which we are fussy about what we consume, in which (in video games, for instance) we have become characters in the narrative who can influence its outcomes, and in which there is a pressing need for a proactive and critical ‘take’ on the way we live our lives and interact with our environment. As the balance of agency shifts within the broader society, schools and their teachers need to transform the most basic terms of pedagogical engagement to make a useful contribution to the emerging social world. Indeed, teachers may not have much choice but to change the fundamentals of their pedagogy if they are not to frustrate and bore young learners whose dispositions are very different from the children and young people of earlier generations.

See James Gee, Video Games are Good for Your Soul.

Dimension 6: The significance of learner differences

One of the most striking aspects of this shift in the balance of agency is the increasing significance of differences among learners to the process of learning. By collectivising individual learner subjectivities under the label of ‘pupil’ and having all ‘pupils’ move through the same curriculum at the same pace, and by forcing pupils to move towards a norm or standard, earlier modern schooling tried to maintain a veneer of sameness. To a large extent, however, and somewhat ironically, it achieved this veneer by creating its own, special form of difference; by ranking learners against an average or norm, such that many learners – those who fell ‘below’ the ‘norm’ – literally failed. When we take learner identities into account, we encounter a panoply of human differences that cannot be ignored in the configuration of educational experiences – material (class, locale, family), corporeal (age, race, sex and sexuality, physical and mental abilities) and symbolic (language, culture and identities of gender and sexuality). In fact, not dealing with difference means excluding those who don’t fit the norm. It means ineffectiveness, inefficiencies and thus wasted resources in a form of teaching that does not engage with each and every learner in a way that optimises their performance outcomes. It also cheats the learners who happen to do well in the system – those whose learning styles and habits happen to be accommodated in the one-size-suits-all curriculum. It limits their exposure to the intellectual and personal experience of cultural differences and different ways of knowing so integral to the contemporary world.

Dimension 7: The relation of the new to the old

Notwithstanding the trajectory of change, one of the peculiar things about the New Learning is that none of the old has gone away. Didactic teaching of subjects-in-themselves is alive and well today in the form of ‘back-to-basics’ curriculum, teaching to standardised tests, stimulus–response approaches to e-learning, and in teaching fundamentalist religious doctrine. As often as we encounter future-oriented innovations in education, we also encounter ‘back-to-the-future’ views of what we need to do to address the difficulties of our times and the uncertainties of our future. These are as much features of education today, indeed are more dominant in many educational systems, as is New Learning. Sometimes, what is presented as new is, in fact, old; and sometimes what is presented as traditional is new insofar as it is a reaction to contemporary social anxieties. Didactic teaching may at times even still have a place. There may be moments when it is appropriate. Rote learning, for instance, may still work, at least in part, at certain times and in certain places for certain kinds of knowledge. Moreover, when didactic teaching is connected with traditional cultures, we are obliged to respect it because we are committed to living in a society that values social pluralism. Or, at least, our respect should be offered only so long as traditional pedagogies and educational institutions do not disadvantage learners or produce outcomes that are incompatible with democratic pluralism itself. Moments of older learning are, in other words, an integral part of the world of the New Learning.

Dimension 8: The professional role of the teacher

To juggle all these relations – of agency, diversity, learning outcomes, institutional locations – this is the challenge for the new teaching professional. And ‘professional’ is the operative word. The ‘old’ teacher was constructed as a person who habitually took and followed orders; whether as a public servant or member of a religious order. The new teacher is an autonomous, highly skilled, responsible manager of student learning. The old teacher shut the door of the classroom and, apart from the per- iodic visit from an ‘inspector’, this was their private fiefdom. The new teacher is both grounded in the community and a corporate player, a collaborator and a member of a self-regulating profession. The old teacher was an instrument in a bureaucratic system or religious hierarchy. The new teacher is not simply a public servant or someone bound by bureaucratic accountabilities, but a learner – a designer of learning environments, an evaluator of their effectiveness, a researcher, a social scientist and an intellectual in their own right.