Civic pluralism: Towards New Learning

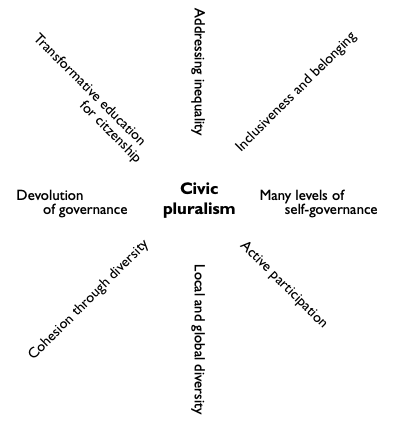

The ideology of neoliberalism, its critics argue, promotes a relationship of civil society to the state that is far from stable and sustainable in a practical sense and often far from satisfactory in a human and ethical sense. The idea of civic pluralism was developed as a part of our research and policy development work. It is an idea that attempts to be both realistic about what may be possible in the current social and political context and supportive of attempts to imagine a more open, inclusive and just civics. The implications for education are fundamental. The kinds of persons that education creates – right down to the basics of their skills, motivations and dispositions – are vastly different today than what was required for adequate citizenship of the nationalist state. We want to put the case that civic pluralism calls for a New Learning.

See Civic Pluralism Case Studies.

Dimension 1: State power

As the state shrinks, disturbingly increased inequalities are created by the unrestricted market. A dog-eat-dog ethic of competition prevails and so much personal responsibility is laid on individuals that life often becomes a struggle to keep up. Few, however, would want to turn back the clock and return to the kinds of strong states in which many people lived in the 20th century. Oftentimes the big 20th-century states deprived people of their liberties – the fascism that ravaged Europe and East Asia at the middle of the 20th century and the Stalinist-style communism that, by the time of the neoliberal turn in the last quarter of that century, encompassed one-third of the world’s population. Nor would many people want to go back to the barely satisfactory conditions of life offered to less-affluent social groups by the welfare states of the 20th century. The offerings of the welfare state were at best minimal, and delivered by a paternalistic bureaucracy that provided communities with what it thought was best for them – barely basic, one-size-fits-all health, schooling and welfare.

Civic pluralism is a way to manage the relationship between the state and civil society that offers a modicum of justice without the restrictions to liberty that so often accompanied the bigger states of the 20th century. Sometimes for the better, the old top-down relationship of state to citizen is being replaced by multiple layers of self-governing community, from the local to national and global levels. Considering the more positive side of this equation for the moment, this means that there are many more realms of participation. There are many more opportunities for self-governing citizenship in a broader sense: in local communities, in workplaces and in cultural groups, particularly as the new technologies enable people to voice opinions and get a broader hearing than ever before.

Recall Henry Ford’s workplace. The more innovative of today’s workplaces offer expanded space for participation; in fact, they require greater responsibility and self- governance at every level, from the smallest working team to the kind of consensus bosses are supposed to create through their consultation and strategic planning processes. The balance of agency has shifted in such a way that workers have to act more like citizens, as participating members of their close working groups and of their organisation. And organisations need to make sure they are good citizens of the broader community, given the ethical responsibilities to be mindful of the consequences of their actions – the safety of their products and services, the appropriateness of their offerings to different niche markets and the environmental consequences of their actions. In these senses, a person at work has to be more of a citizen today than was required or possible in the Fordist workplace.

In the domain of citizenship, the dynamics of belonging and governance now occur at multiple and overlapping levels – from community organisations and workplaces to self-regulating professions, to communities of common knowledge and shared taste, to the increasingly federated layers of local, regional, national and supranational government. We witness the rise of these kinds of self-governing structures in many areas of civil society. The Internet is governed, not by any state or coalition of states, but by the World Wide Web Consortium, a group of interested experts and professionals who cohere around elaborate processes of consensus building and decision making. Professional standards are increasingly developed by the professions themselves – teaching less so than other professions as a consequence of its historical links to the bureaucratic state, but it may be a worthwhile agenda for teachers to take increasing control of their own professional standards. And schools, which were formerly the objects of command at the nether reaches of bureaucratic hierarchy, increasingly have to regard themselves as self-managing corporate bodies.

With the decline of the centralising, homogenising, authoritarian nation-state, power and cultural influence are being realigned, to locally diverse communities, as well as to transnational forms of government, such as the European Union, and to global webs of influence (business, trade and the media). People increasingly find that they have multiple citizenships, sharing the responsibilities of governance in different ways in different parts of their lives. This process occurs in self-regulating professions, or sporting associations, or in ethnic diasporas that allow you to vote in elections for places in which you do not live as well as the place where you do live, or in indigenous communities insisting their unique sovereignty over native lands be recognised. As a consequence, the nation-state is arguably becoming less relevant as a focal point for citizenship or even cultural identity.

See Habermas on Globalisation and Governance.

This means that, in place of centralised bureaucratic control, federalism and subsidiarity are finding a place as guiding principles. Federalism in a broad sense means multiple and overlapping sites of self-government, whether geographically defined (national, state, local); defined by culture and ethnicity (indigenous self-government, ethnic community groups); defined by expertise (professionals, hobbyists, volunteers); or defined by institution (educational, medical, corporate). Subsidiarity means that certain coordinating, negotiating and mediating roles are delegated from the more particular and localised of these sites of self-governance to the broader and more general. The power of the more general is founded on the commitment to delegation on the part of the more particular. This reverses the logic of delegation inherent in the nationalist state. The result is an apparent paradox: cohesion through diversity.

See Handy on Federalism and Subsidiarity.

Seemingly intractable problems persist in our civic life. The disparities between the haves and the have-nots seem to be growing all the time, exacerbated by the unrestrained market. Competition and individualism do not necessarily produce harmonious social relations and comfortable cultural conditions. And, despite its protestations, the neoliberal state is not a reliable friend of democracy. The same politicians who advocate a small state in favour of the market often ignore long-cherished civil liberties when it comes to trying to root out terrorism or stem the low of undocumented immigrants and refugees.

See Hilton and Barnett on Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism.

Dimension 2: Public services

Neoliberals say the removal of the ‘nanny’ state means that citizens have to take more responsibility in choosing their welfare options in the market, such as pay-for-yourself pension schemes, private health insurance and user-pays education. They also say that competition will temper the complacency and arrogance of bureaucratic monopolies, such as government welfare agencies, public hospitals and public schools. It will force them to improve their offerings and provide better services. It will encourage them to differentiate their offerings from others. Using these quasi- market mechanisms, the neoliberals argue, public and community organisations can prove their mettle, and even attract expanded ‘market share’. Their criticisms of the older public offerings of the welfare state may in some cases be justified, but it is far from clear that the market does a reliably better job, particularly for the poor and the disenfranchised.

In fact, to the extent that the self-governing spaces in civil society are opened up by government retreat and tax cuts, formerly important areas of activity for the welfare state may be doomed to penury and failure; for instance, public schools and hospitals whose quality is terrible despite the best intentions of the people who work there and the aspirations of the communities they try to serve. Such failure may begin a dangerous slide into a sometimes not-so-civil society.

The underlying principles of civic pluralism are equivalence, devolution and diversity of service provision. The meaning of social entitlement and fairness changes – to have equivalent access to services does not mean you will be provided with the same services but services whose social outcomes are equivalent. You don’t have to be the same to be equal. To achieve this, government supports groups providing services for themselves (such as community support groups or community based, non-government schools), giving them a considerable degree of autonomy in creating what works best for them, be that schools, or aged care, or the arts, or media. This is the principle of devolution. The outcome is diversity – of approaches, services, institutions, cultures and communities. There is still an important place for taxpayer funding of services that will never be provided by the market. And any such devolved services need to be supported by regulatory mechanisms in the form of standards, and audit of outcomes in relation to service objectives.

Arguably, too, the welfare state with its mass, generic services often used resources inefficiently. For instance, the result of a generic, regimented, one-size-fits-all curriculum was that many learners failed (the ones the curriculum failed to engage). This meant that a lot of public resources were wasted on educational bureaucracies, buildings and teachers. Instead of a big state providing generic services for a mass society, we need a sufficient and efficient state helping communities to help themselves in their own, particular ways.

Dimension 3: Belonging and citizenship

As citizens, we now simultaneously belong to many more kinds of communities, at the local, the regional and the global levels. Singular citizenship, in which a per- son is exclusively a member of a nation-state and the electoral process is the sum total of their participation, is being replaced by multiple citizenship, in which there are many places of belonging, and thus many overlapping forms of self-governance. Participation is not just a matter of voting. It is about living actively and contributing in many different spaces. The way you participate in each of these places and the way you belong are distinctive and different or special to that place.

See Charles Taylor on the Politics of Multiculturalism.

Civic pluralism is a response to the changing shape of the state and its relationship to civil society. In some moments, civic pluralism is limited and pragmatic. In others, it is optimistic and utopian. It is a concept that makes space for citizens to create a culture of civility and a sense of belonging, among people who live in close local and global proximity but not necessarily of the same kin group, whose values are varied and whose life choices at times may seem at odds with each other.

Differences are honoured by measures of self-government at many levels, from local to supranational. They are honoured aesthetically through the variable iconography of place. The phenomenal growth in tourism is a kitschy version of this honouring of differences. This new sensitivity has had noticeable effects to the extent that the bulldozers of generic development are now halted with increasing frequency by activists who want to preserve environmental heritage values – the fabric of uniqueness and the value of difference in place.

The nation-state certainly does not disappear. Nor do diversity and globalisation force it to become uncommitted in a cultural sense, even though the old story of one people, one nation has become unbelievable and, in its more exclusionary forms, unacceptable. Rather, the nation-state becomes deeply committed to pluralism and its procedures as a means of getting buy-in and achieving legitimacy. It remains infused with the symbolism and narratives of belonging. But now they are narratives of diversity, inclusion, collaboration and cosmopolitanism. It remains committed to redistributive justice, but recognises that redistributive justice has to work with the raw material of varied life experiences. It strongly commits itself to access to the material resources, social services and symbols of national belonging but without prejudice to the differences between the life experiences of its citizens. Government needs to become a more neutral arbiter of differences rather than an advocate of a single cultural vision, as was the case in the era of nationalism. This is particularly the case as we move from more local and specific to more general and federal levels of government – from indigenous community self-government to national government, for instance, or from an ethnic community run school to a regional or national education system.

See The Charter of Public Service in a Culturally Diverse Society, Australian Government.

Dimension 4: Learning civility

The educational basics of the old citizenship were grounded in what was then considered to be a necessity: to forge national strength by creating cultural homogeneity. Old schooling inculcated loyalty to the nation-state. The moral lesson of its predominantly didactic pedagogy was that the singular image of the nation-state, and the forms of knowledge and power it valued, were to be unquestioningly accepted.

In an era of civic pluralism, by contrast, the New Learning fosters an active, bottom-up citizenship in which people assume self-governing roles in the many divergent communities in their lives – in their work teams, their professions, their neighbourhoods, their ethnic associations, their environments, their voluntary organisations, their social networks, their affinity groups. Some of these communities may be local and physically co-located. Others may be virtual and dispersed globally. A pedagogy of transformation is better suited to this world of civic pluralism: developing the skills and sensibilities of active citizenship, forming learners who are capable of contributing their own knowledge and experiences, and negotiating the differences between one community and the next.

Education is one of the key areas of responsibility for the state of civic pluralism. Unlike the education systems of nationalism, the state of civic pluralism is agnostic about the lifestyle and values differences it encounters in civil society; until, that is, these threaten that society’s civility. One of the keys to this civility is that the state has a responsibility to ensure comparable outcomes. This does not have to mean sameness of outcomes of the exclusionary kind that characterises one-size-fits-all pedagogy and assessment. Rather, the aim should be equivalent outcomes, measuring comparabilities to ensure that the school provides outcomes for its students that are not the same, but of the same order, as those provided by other schools.

See Schooling in the World’s Best Muslim Country.

The cultural openness of education in a state of civic pluralism paradoxically represents a deep civic and ethical commitment. If the social contract represents a pledge to create a sense of belonging for all, and if civics is something that entails deep responsibilities as well as rights, then civic pluralism points us in the direction of a new social contract. In this social contract, citizens don’t have to be the same to be equal.

This new civics means that schools should teach new kinds of social competence and new forms of ethics. They must develop in students an ability to engage in the difficult dialogues that are an inevitable part of negotiating diversity. Students need to learn the morality of compromise in which parties to negotiations are willing to meet and negotiate on ground that they do not necessarily share in common. They need to learn multiple citizenship in both the literal sense of being a participating member of more than one nation-state and the metaphorical sense of participating in a range of public and community forums. These are some of the basics of a new, multicultural citizenship.