Knowledge relativism: More recent times

Some ways of knowing are less certain of their own rightness. They are less commit- ted to the idea that their ways of knowing are superior. Epistemological relativism, cultural relativism and postmodernism are three such ways of knowing, each overlapping with the other in significant ways.

Dimension 1: Ways of knowing

Epistemological relativism

Epistemology is the philosophy of how people come to know. Religious faith, empirical observation, reasoned argumentation and canonical truths all have their own characteristic epistemologies. They have within them a theory of knowing, and thus learning. Religion, empiricism, rationalism and canonical knowledge are all highly committed epistemologies.

Knowledge relativism, by contrast, is less certain about ways of knowing and their outcomes in the form of knowledge. Whatever you think you know is only ever relative to your experiences, your interests and your perspectives. From person to person, location to location and culture to culture, knowledge varies. The differences arise because everyone interprets the world in ways that reflect their position and their viewpoint. Everything you know is relative to who you are and how you see things. You can only know what your way of knowing allows you to know. It follows that you can only learn what your way of learning allows you to learn.

Epistemological relativists acknowledge that other people can and often do see things differently. There is no problem with this. One of their daily assumptions as they encounter others is a kind of epistemic tolerance. Others may live by other truths. When the epistemological relativist encounters someone who has a different way to truth, they can say, ‘You seem to know what you know, and if what I know is different it is because our ways of knowing are different. Our perspectives are different. And what you think is good for you may indeed be good for you. How would I know if it wasn’t? And who am I to have an opinion? But let’s not argue. I’m pretty sure of what is good for me. You’re welcome to your views, and I’ll keep my views to myself.’

The epistemological relativist regards knowledge as provisional. Something that seems to be an accepted truth might be true for today practically speaking or it may be true for people living in a particular community. But certainties can always be shaken by change, conflict, debate and disproof. Knowledge, in this view, is fluid and contestable. You need to keep an open mind in case what you currently think might prove to be wrong (Blackburn 2005).

See Sextus Empiricus, The Sceptic, On Not Being Dogmatic.

Here are ways in which epistemological relativists approach some of the knowledge concepts and practices found in the more committed ways of knowing:

Facts: There is no such thing as a definitively proven fact. Facts are products of perspective. For example, the fact of the date of the ‘discovery’ of the Americas or Australia changes when one questions the notion of ‘discovery’. The world is only a figment of our construction of the world, through our languages, imageries and ideologies, for instance.

Reason: The universal, reasoning individual does not exist. There is no universal person who can measure everything from the point of view of a single-minded ‘reason’, valid for all people and all times. Rather, there are interpretations in the plural, the products of different material (class, family, locale), corporeal (age, race, sex and sexuality, and physical and mental characteristics) and symbolic (culture, gender, affinity) attributes. There is no ultimate ‘reason’, just varied subjectivities and identity perspectives.

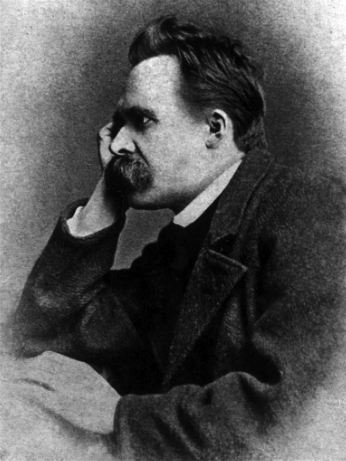

See Nietzsche on the Impossibility of Truth.

Canonical texts, sacred and secular: We can only be suspicious of meta-narratives, or master narratives that try to present all-encompassing spiritual, scientific or historical stories. They have a habit of leaving out the knowledge and perspectives of those who are not powerful. Competing interpretations, moreover, seem to cancel the pretence each has to absolutism – how can the Darwinian view of natural his- tory square up with the theory of intelligent design by God, when both purport to be definitively correct? The knowledge relativist warns us that we should approach any such texts with a warily critical eye, deconstruct or dismantle their premises, trace their origins or genealogies and measure them against the practical stuff of culture, power and interests. Then we might be able to uncover the limitations and expose the totalising pretences of narratives that would want to claim universal truth. And what is the role of the reader, who may interpret the same text or theory in very different ways? (Eco 1979) Canonical texts appear to speak unequivocal, transparent truths, intended to be absorbed by readers and learners, and always with the same meaning. A person’s reading of a text – what they see in it, and don’t see in it – the epistemological relativist would retort, depends on their experiences, interests and reading position. Besides, who is to say that the canon has a special status? One person’s canon is another person’s irrelevance.

The stance of the epistemological relativist seems eminently reasonable, pragmatic, modest, undogmatic and generously flexible. It allows that other people with varying perspectives and interpretations might be right, even though from one’s own, current perspective they may not seem right. If you are an epistemological relativist, you’re more open to the possibility that the other person could convince you that they are right. And if the person can’t, or doesn’t, or won’t, you can still agree to differ and respect their right to differ.

The relativist stance is also explicable in the light of our historical experience of committed knowledge frameworks. History provides sufficient cause to take fright at the consequences of dogmatic certainty. Consider the technologists and scientists who knew their facts but didn’t consider sufficiently the consequences of applying their knowledge. Or consider the dictatorial leaders of imperialist, fascist or communist states who thought they knew what was best for their supposedly backward populaces. Consider also the religious fundamentalists who have fanned the flames of terrorism and sectarian violence. Relativism is a modest assessment of whatever we think we know. It makes for more careful and circumspect knowledge making. It is less arrogantly confident about what we know and our powers of knowing. It means we are less likely to want to impose our views on others.

However, relativism’s critics argue that our everyday experiences tend to point to the existence of an underlying reality. It is hard to argue with an everyday, mundanely grounded truth. We live our daily lives with things so ordinary that they are nearly unquestionable, and people rarely do. If you touch something hot, you will get burnt. If you hit someone aggressively you will initiate or escalate conflict. These things are so basic that we almost know them instinctively.

The critics of epistemological relativism also point to the practical trust we have in expertise. Whenever we cross a bridge, we trust that the engineers have got their calculations right. Whenever we take medications, we trust the knowledge of chemistry and biology of the medical scientists who developed them and the doctor who prescribed them. In other words, we trust the knowledge of people who know more about a particular thing than we do. We could choose to accept that modern science has more powerful insights on some subjects than a layperson’s casual opinions or ancient religious narratives. So, for instance, if we choose to accept the Darwinian view of natural history because it is more widely held by the international scientific community than the theory of intelligent design, we move away from a position of epistemological relativism.

See Science and God.

Still others claim that epistemological relativism avoids commitment in ways that are amoral and thus unconscionable. If nothing is any truer than anything else, how do we live? If no facts are ultimately more convincing than any others, we can’t really argue with neo-Nazi sympathisers who deny the existence or scale of the Holocaust in which six million Jews were killed. If there are no spiritual interpretations of meaning that are more compelling than any others, then how do we live? If, as the 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche says, human subjectivity consists of nothing more than an ego-driven ‘will to power’, operating ‘beyond good and evil’ (Nietzsche 1901), then where does that leave ethics? If there are no canonical texts, how do we dis- criminate brilliant literature from other writing, or profound and well-crafted cinema from junk TV? Is knowledge relativism so disruptive a choice that it wrecks human cultural traditions, or the idea that some knowledge is more deeply significant or useful than others (Cope and Kalantzis 1997b)?

Cultural relativism

Cultural relativism is the view that everything is relative to a cultural context at a historical moment. ‘If that’s the way your culture does things, that’s fine for you.’ ‘If that’s the way our grandparents did things, it must have been fine for them.’ Committed knowledge, by comparison, tends to be less inclined to notice cultural differences, regard them as significant, or even at times to pay them the respect that they may deserve.

It’s not that there are no truths in the ways of knowing of cultural relativism. For the cultural relativist, the truest you can get is what you know from your lived experience, your feelings, your identity, your subjectivity. You act this way, think this way, are this way. That, surely, you know. If there is any truth at all, it is that to be true is to be true to yourself, to be authentic.

Language plays a big part in framing your self in a world of cultural relativism. It is one of the main conduits that connects the culture in which you are located with your singular personhood. Your ways of interpreting the world are shaped by the way you come to name and speak in the world – in English versus Arabic, or through scientific discourse versus religious discourse, for instance. If there is truth in this sense, it is grounded in the play of language and the ways you have learned to make meaning.

See Wittgenstein on the Way We Make Meanings with Language

See Richard Rorty on Truth and Language.

Cultural relativism seems very reasonable. It is a way of knowing that promotes cultural respect and tolerance. It brackets or tries to set aside our own biases, to as great an extent as possible and at least for the moment, in order to avoid the blinkers of negative prejudgement, ethnocentrism (assuming that everyone sees things, or should see things, the way you do in your culture) and racism (negative views of the inferiority of other racial or ethnic groups). It is a way of avoiding conflict and promoting peaceful co-existence.

Given the history of modern times – colonisation, the injustices committed by the nationalist state and the gross inequalities in modern societies – cultural relativism seems a kinder, gentler way of knowing. Using this way of knowing it is possible to acknowledge the harm done to indigenous cultures and languages by colonisation, the pain inflicted upon less powerful or minority communities by groups with power, and the injustices of education systems that purport to provide a one-size-fits-all education but whose effects are to leave many feeling left out.

Cultural relativism, however, has its strong critics. Some say it is a formula for ‘live and let live’ complacency. It allows you to retreat into your own parochial little space, as though the rest of the world did not exist and did not matter. It’s easy to say ‘live and let live’, but what do you do next? Do you withdraw into a space where you can privately indulge your own prejudices? Cultural relativism is also anti-intellectual when it gives up on debate and discussion with the conclusion, ‘Okay, so that’s what you think.’ It is as though the differences are neutral and innocent and do not require action. (‘So that’s life.’) To the extent that differences also reflect relationships of inequality, a deeper recognition may also suggest an agenda of inclusion. (‘So let’s do something about it.’) You might be a woman and I might be a man, for instance, and it’s not just a matter of recognising the differences. It is also a matter of going one step further and doing something about the historical inequalities that this recognition reveals. Cultural relativism, its critics argue, has a weak moral grounding. It can at times be pragmatic to the point of opportunism. At times, also, its moral relativism is patronising. ‘It may be fine for you, but I would not want to live that way.’ As the ‘other’ in this relationship of difference, you may find that being tolerated is a less than satisfying form of engagement. ‘You find me tolerable, you don’t mind that I exist in my difference, but I can tell you don’t feel comfortable with me and my way of being.’ This can create a sense of distancing alienation.

Postmodernism

Postmodernism, as its name indicates, is a counterpoint to modernism. Often buried in difficult-to-read texts, the only thing that is clear on first reading is what it is not: modernism. Modernism, the postmodernists argue, thought that the empirical world could be discovered through science. It thought technology was a route to progress, development and betterment for everyone on Earth. It created universal laws of human reason (the ‘Enlightenment’), supposedly applicable to all human beings. It put ‘man’ and his interests at the centre of the universe, hence Descartes’ famous statement ‘I think therefore I am’. It created canonical knowledge in the form of agreed scientific theories and a high culture of great literature and great art. These canonical texts, the postmodernists point out, are in fact the creations of ‘dead white males’ and carry with them all the biases and thus limitations connected with their cultural perspectives and their positions of power and privilege.

Postmodernism is a narrative describing the shape of contemporary life that incorporates elements of epistemological relativism and cultural relativism (Lyotard 1979). On the subject of contemporary life, postmodernism does not draw a distinction between high culture and low. It is as interested in the barrage of signs in the new media as it is in any other text. Who can judge what is better: a Shakespearean play or a five-minute sitcom on YouTube? If the measure is the number of people involved in cultural engagement on any one day, it may even be the sitcom on YouTube that wins. Who’s going to be so elitist as to tell the YouTube viewers they are wrong?

Postmodernism also criticises what it regards to be the eurocentrism, or male-centredness, or heterosexual biases of Western culture (Spivak 1999). Instead, it recognises and makes a virtue of decentring contemporary culture. There is no culture in the singular, just many cultures in the massively plural. This may be read as fragmentation. It may be interpreted as giving up on utopian social projects. But the postmodernist will tell you that utopian projects with totalising pretences all too easily end up as totalitarian nightmares, as did the communist utopias attempted in the 20th century. One of the main exponents of these ideas has been Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

When it comes to underlying ways of knowing, postmodernism does not allow that any single worldview could be better than any other. There are no intrinsically privileged forms of knowledge. Nothing is necessarily truer than anything else. Modernism’s ‘logocentrism’ placed universal reason at the centre of everything. Postmodernism recognises the many and varied forms and sites of feeling, subjectivity, desire and identity. Instead of modernism’s faith in the methods of science or history, postmodernism cautions that you should never take the facts at face value. Behind every purported fact is a person or group in pursuit of their own interests. Don’t trust the master narratives that try to tie together all the facts and principles, to universalise, to be all-encompassing and thus to totalise. They are only ever the product of a sectional interest and of people who would wish that everyone would see things the same way they do. There is no truth out there, just ‘constructions’. There are no definitive knowledge sources, just discourses reflecting particular interests.

So if you are a postmodernist, what do you do? First, recognise that all you see is bricolage: lots of shreds and patches that happen to fall together as knowledge. Abandon the Enlightenment conceit that anyone can put together a bigger picture or a deeper picture. The most you can discover is that a bit of this (identity, experience, discourse) happens to sit beside a different bit of that. If we want to find out some more, we might deconstruct, or work out which bit of identity sits beside what kind of discourse. We would do this, not in order to unveil any underlying truth, for that would be to fall into an Enlightenment trap. ‘Deconstruction’, in fact, helps us find that the grand narratives are not so grand. Rather, they are the products of sectional perspectives, contingent interests and passing power plays (Derrida 1976). Then, we might make postmodern knowledge by playful collage, paradoxical quotation and irreverent irony, juxtaposing one kind of meaning beside another and observing the not much more than accidental cross-currents. Our knowledge-making mode becomes more like pastiche than the modernist’s earnest consistency or commitment to one mode of cultural representation or discourse (Jameson 1991).

Postmodernism has its vehement critics. They use much the same arguments as those use to attack epistemological and cultural relativism. And one more: for all its purported lack of commitment, postmodernism ends up looking pretty committed. Or, at least, this is how it seems whenever it faces down fundamentalist religions, or Western science, or pragmatists who trust their sense that something really exists in the world beyond the projections of our discourses. Then, postmodernism seems a quite definite position itself. In fact, it looks like a variant of Western liberalism, as irritated by other points of view as any explicitly committed knowledge. Postmodernism plays a game of false modesty. It sometimes seems to protest its lack of commitment too loudly.

Dimension 2: Ways of learning

Relativist ways of knowing embody an approach to learning that is quite different from ways of knowing that openly proclaim their commitment. In the classroom, the teacher may value the many points of view of their students. They may consider the ‘popular culture’ of the students to be of equal value as an object of study to the ‘high culture’ of the traditional curriculum. The teacher may go out of their way to incorporate the cultures and discourses that students bring to the classroom from their every- day lifeworld experiences. They may value different ‘learning styles’ or the varied ways in which learners feel more comfortable learning. The teacher may also employ a ‘critical pedagogy’ in which students examine their own experiences and the knowledge sources they encounter for their biases, perspectives and ways of thinking (McLaren 1995; Aronowitz and Giroux 1991).

In the curriculum, different points of view might be presented without insisting on the correctness of any one point of view, explicitly or even implicitly. This may require the neutral presentation of different interpretations. For instance, the curriculum may present evolution and intelligent design, as though each were equally valid perspectives and despite the fact that many scientists, on the one hand, and many fundamentalist Christians or Muslims, on the other, genuinely believe that the other interpretation is plain wrong.

Between one school and the next, a certain regime of relativism applies, too. A private or community school may have been established in order to inculcate its young learners with its epistemology and knowledge, and because it disagrees with the secular or relativist worldview presented in the public school. The teachers at the public school may say, ‘That’s fine, they’re welcome to their way of teaching and learning. But we have our standards and principles of cultural relativism and critical pedagogy because we are an open, diverse, public school, and we are going to maintain these steadfastly.’

See Aronowitz and Giroux on Postmodern Education.

These moves are typical of what we have called authentic education. However, they also bring with them difficulties that are common in this approach to teaching and learning. Are we addressing inequalities adequately? Are we being entirely honest if we do not consider this to be based in anything other than another, equally committed culture of knowledge and learning: the culture of relativism?

See George Pell on the Dictatorship of Relativism.

Dimension 3: Sites of learning

As an approach to education, knowledge relativism seems eminently reasonable, sensible and just. It may, however, produce a fragmentation of learning. Schools supporting a wide range of interests and perspectives in their curriculum may come to feel like a shopping mall of knowledge in which learners can pick and choose their own ways and means. When education is based on knowledge relativism, it seems to be contributing to a broader sense of social and cultural fragmentation.

More seriously, however, this fragmentation may mask ongoing inequalities. School X is different from School Y because the students are different, and by creating ‘relevant’ learning the school is being true to students’ differences. But do the students from each school enjoy comparable outcomes? Course or Subject X is different from Course or Subject Y, true to the interests of the students in each. But do students in the two groups enjoy equal opportunities to further their education? Is there a comparable social effect once they have finished their courses? Student X may be working on something close to their interests, and Student Y on something close to theirs, but will this produce equivalent results when it comes to measuring their learning outcomes? When Student X is studying popular culture (because that’s what this student relates to closely in their lifeworld) and Student Y is studying ‘the greats’ of the canon (perhaps because this student has lots of books at home, and that’s what their academically inclined parents value) will they necessarily end up getting the same end results from their schooling? Perhaps it shouldn’t be this way, but inequality of social opportunity may prove to be the outcome.

The key questions, then, are: To what extent do all our efforts to provide varied sites of learning and modes of engagement put a deceptively democratic gloss on what sometimes turn out to be pathways to inequality? When does our ostensible sensitivity to differences, do differences an injustice?