Synthesis: More recent times

In synthetic pedagogy and curriculum, the learner can deconstruct knowledge, and even reconstruct knowledge, but mostly in a way that leaves that knowledge more or less unchanged. The learner takes the building blocks of knowledge they have been given, takes them apart and reassembles them the way they are supposed to.

Dimension 1: Pedagogy

Synthetic pedagogy encourages learners to get actively involved in their learning. This may involve doing their own empirical work, such as conducting a scientific experiment. Or it may mean showing their workings so they demonstrate that they have ‘understood’ mathematical theory. Or they may write an essay that shows they have internalised the ethics, styles or sensibilities of a text of the literary canon.

More than superficial repetition of knowledge in a pedagogy of mimesis, this synthetic work shows a deeper ‘understanding’. This also means that particular knowledge of something specific can be transferred to another area. Synthetic pedagogy shifts the balance of agency towards the learner to some degree by allowing the learner space to appropriate knowledge for themselves.

See Froebel on Play as a Primary Way of Learning for Young Children.

Synthetic pedagogy may also get the learner involved constructing knowledge according to a given formula and demonstrating their learning of the formula. For example, following a prescribed experimental methodology in science, a student may be able to demonstrate a correct result and a correct process. Applying a mathematics theory, they might be able to get the right answer, showing how they can apply the theory. The outcome of synthetic pedagogy is that you come to an accepted understanding of a part of a presented body of knowledge or discipline. You get the right answer more knowingly than you would if you were simply presented with that knowledge as fact, theory or canonical text. But it is the one answer and the same answer that mimetic pedagogy would have had you learn.

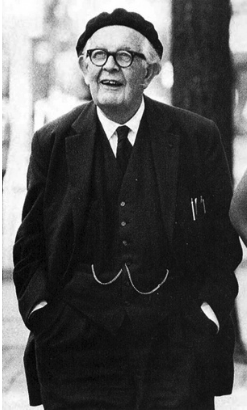

‘Constructivism’ is an example of synthetic pedagogy. One of its sources is the work of the child psychologist Jean Piaget. He made the case that knowledge is not simply absorbed by the child learner from what they are presented. Knowledge is, to a significant degree, constructed by the learner (Piaget 1929; 1976). The learner internalises and builds their cognitive capacities as they progress from one developmental stage to the next. In other words, learners build their knowledge and underlying capacities to know through engagement with the world. Learners are not simply given understandings. They build understandings. This is the basis for a learner-centred interpretation of the learning process.

See Thayer on Making Curriculum Relevant.

A postmodern version of synthetic pedagogy is grounded in learners’ identities. In recognising social differences and the experiences of historically neglected or marginalised groups, teaching programs may be developed that bring the cultures of learners into the learning process. The raw material of learning may connect with learners more directly. Their lifeworld experiences and interests can be brought into the curriculum. However, the critics of this approach often question whether the learners would have been better off if they had been studying the language of power or the methods of scientific reason, rather than wasting their time on stuff they already know. If the synthesis is just a deconstruction and reconstruction of existing knowledge experiences, where does this take learners?

Synthetic pedagogy can also be criticised for placing the individual at the centre of learning processes. Constructivism, for instance, focuses on in-your-head cognitive development. This is sometimes at the expense of a balanced understanding of the complementary role of the social. Vygotsky, for instance, would claim that knowledge and learning are deeply social. A developing child’s learning is shaped by the conceptual frame of reference in language they have learned in their culture and continue to learn in school as language becomes conceptual (Vygotsky 1934). The child doesn’t simply invent the world for themselves. They reinvent a social world in which they are enveloped.

Synthetic pedagogy may encourage lots of learner activity. But is it always the kind of activity that promotes deep intellectual growth? Its danger is to create ‘busywork’ in which the learners have their time filled with tasks but not ones that stretch their intellectual capacities or take them out of their zones of cultural comfort. At worst, this kind of pedagogy might be a waste of time. In the name of ‘appropriateness’ or relevance, it may serve to hamper the progress of disadvantaged students.

At other times, it may be little more than another method of reaching traditional curricular and disciplinary ends, and this could have been achieved by means of the quicker and less circuitous and thus faster route of mimetic pedagogy. Learners actively piece together bits of knowledge, but only from the clues that have been presented by the teacher. Their syntheses often amount to not much more than second-guessing the answer that’s in the teacher’s head. Learners sometimes complain that it would have been easier and quicker just to have been told the answer they need to know rather than having to go to all this trouble to figure something out for themselves. Why bother with the activities when there is still really only one answer to each question and one solution to each problem? And what is the role of the teacher other than a manipulative one – to lead the learners to their answers while avoiding telling them the answers directly? The cultural assumptions behind this kind of knowledge making are rarely spelt out, and favour some students ahead of others. Some learners thrive in ego-directed, individualised, inquiry learning, while others who come from different cultures of knowledge creation and whose learning styles are different, fall by the wayside.

Despite pretences to cultural openness, even the most democratic of synthetic curricula may be profoundly culture bound. The African-American educator Lisa Delpit highlights this kind of cultural disjunction at the level of classroom discourse. What appears to be an open, child-centred, democratic pedagogy is, she argues, a culture-laden imposition. In contrast to the culture of African Americans, liberal discourse uses veiled rather than explicit commands. Under the cloak of child-centredness it is another discourse of adult authority. ‘Would you like to do this next, Betty?’ White children know that this means they are expected to do something. To African-American children, the white liberal teacher who operates in this discourse appears to have no authority, and the class reacts accordingly. The problem for African-American students is that they may misread the cues when authority is expressed in ways that are unfamiliar to them (Delpit 2006).

See Lisa Delpit on Power and Pedagogy.

Dimension 2: Curriculum

Synthetic curriculum gives teachers more scope to piece together learning programs at the school level. It allows them to customise the curriculum development process and create programs that it the needs of their learners.

See Bruner’s Theory of Instruction.

The rhetoric that supports synthetic curriculum development includes terms such as ‘relevance’, ‘needs’, ‘diversity’ and ‘choice’. Curriculum is created to meet the needs of particular students in a particular community. For that, it is a more democratic curriculum. Instead of forcing official, disciplinary knowledge onto learners, a locally appropriate synthesis of subject offerings and subject content is negotiated between learners, the community and teachers. This gives teachers more control over curriculum, and more responsibility: an approach called ‘school-based curriculum’ (Boomer 1982).

See Moves You Make You Haven’t Given Names To.

However, synthetic curriculum also attracts its critics. If the synthesis for schools in poorer communities happens to prepare students for certain kinds of non-professional destinations in the labour market, or to ill their time with ‘Mickey Mouse’ subjects, does this also mean that the curriculum has surrendered to inequality and doomed learners to a certain, limited kind of relevance? Does the negotiated, synthetic curriculum conspire to lower the sights of learners in the name of relevance and realism? It may engage learners, to be sure, but without extending their intellectual capacities or broadening their life horizons. Meanwhile, more privileged students in advantaged schools do subjects that will get them the marks to get into the more prestigious streams of higher education. Does this amount to school streaming by means of which curriculum participates in the reproduction of social stratification? To tread gently around the relationships of difference may seem democratic, but this kind of synthetic curriculum may also serve to rationalise social division, even when it is framed in the nicest-sounding rhetoric of relevance and diversity.

Despite the shift in the balance of agency, synthetic curriculum often leaves the learner and their world substantially the way they are. Learners put things together, but only from what is given to them in the curriculum. They are more active knowledge makers than they would have been in mimetic curriculum, but mostly this does not go too far beyond second-guessing the answers required by the teacher, the curriculum and the discipline. They deconstruct knowledge but only to reconstruct it in more-or-less its received form. This is not enough for a society that now puts so much store on responsibility, participation, creativity and innovation.